Newsletters

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Newsletters for 2022 are published here.

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Last Month’s Talk

The Branch finally was able to hold a meeting at the Armoury. Captain Lesley was present and her pleasure in seeing the Branch again was mutual.

David Dunham gave an interesting oversight of the deployment of the British Army at Cannock Chase and invited us to meet him there on the following Sunday, for a guided tour of the site. It had housed thousands of soldiers for training and also enemy POWs. He also brought also a number of artefacts including a Lee Enfield and a German Mauser.

On Sunday several of us travelled to the base. David met us and invited us to inspect a wooden hut laid out as a bedroom for the enlisted men. He then took us to the firing range. Although much of the area is now overgrown the still dominant butte is outstanding.

The butte was used as a protection from shots that missed the targets. Returning back it was possible to pick out the old firing trenches in which the soldiers used during musketry training. These were in staged distances and at 2000 yards it was amazing that even at that range experienced marksmen were encouraged to fire a round at that range as it could still inflict a fatal wound on the enemy.

As well as the graves of British soldiers the Chase also is the resting place of enemy soldiers. Many of these would have been in poor health on arrival at the German POW camps. These included men who had been shot down in aircraft and airships attacking our mainland.

The Chase, a former Royal forest, covers 26 square miles. In the autumn of 1914, only months after the start of the First World War, construction of two large camps began on Cannock Chase. The camps (known as Brocton Camp and Rugeley Camp) were constructed with the permission of Lord Lichfield, on whose estate they were being built. The infrastructure for the camps, including the water supply, sewage systems and the roads all had to be created from scratch before work could begin on the huts and other structures.

The camps, when completed, could hold up to 40,000 men in total at one time and trained upwards of 500,000 men during the war. They had all their own amenities including a church, post offices and a bakery as well as amenity huts where the troops could buy coffee and cakes, or play billiards. There was even a theatre.

The men were housed in wooden block houses of 20 men, whereas in the same sized hut fewer officers were housed individually in a private room. (There is only one hut remaining which is furbished as it would have been and volunteers dress in period costume).

Cannock Chase War Cemetery contains 97 Commonwealth burials of the First World War, most of them New Zealanders, and 286 German burials. There are also three burials of the Second World War. The 58 German burials in Plot 4 were all brought into the cemetery in 1963, as part of the German Government's policy to remove all graves situated in cemeteries or war graves plots not maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Many of the German graves contain airmen whose Zeppelin or Gotha was shot down.

Cannock was also used to provide a scale model of Messines and the troops who were to attack it were able to view it in advance of the assault. Rediscovered a few years ago it was notated and then reburied.

It was good to have the Armoury

back as the Branch meeting place and also to have a live speaker which enables a much more meaning interface.

Thanks also to David for his expertise and organisation of the talk and tour.

Terry Jackson

The butte

The group at Cannock Chase

Inside the refurbished hut

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Chairman’s Comment

We continue into the new year under the most severe lockdown arrangements and I think the majority of people realise we all must continue to show self-discipline and resilience to see these ‘strangest of times’ to a conclusion. With January now passed daylight is lengthening and we are moving towards springtime with a renewed optimism that better days are on the horizon.

This coming Friday 12th we welcome our old friend and long-time member Bill Mitchinson for his talk on the eleven battles of the Isonzo.

Next month’s talk, 12th March, will be given by Trevor’s wife Caroline. Her talk is about a lady whose grave Trevor and Caroline saw in Mikra, a suburb of Thessaloniki (aka Salonika), CWGC cemetery whilst visiting Greece. The lady in question is Gladys Murray Levack. See the full article currently on the North Wales website. https://www. nwwfa.org.uk Incidentally, Caroline recently had an email, out of the blue, from an American academic about her article.

There is a massive online interest in the Great War worldwide and all our WFA websites receive unbelievable visitor levels which is a credit to all concerned especially Trevor who does our website, http://www.landcwfa.org as well as North Wales Branch. If you have any articles or short stories of a family ancestor these will always be of interest to our readers and will be used online or in print space allowing.

I welcome you all with this first edition of ‘Up the Line’ for 2021. The WFA national website editor and development trustee have created many items of interest, see www. westernfrontassociation.com, to catch members’ attention and entertain. Great War reading and research time will probably be a useful distraction for all depending on your level of historical interest.

When meetings will return us to the Armoury is anybody’s guess but let’s keep fingers crossed.

You will have just received the January edition of “Stand To!” with twelve interesting articles arranged by the WFA’s new editor Matt Leonard. We wish him well in taking over the journal after the sad loss of Jon Cooksey. After thirteen years of working together on ST! I still find it hard to believe Jon is no longer with us.

The next edition of Bulletin (119) is my current distraction and I can promise you some interesting material when published, hopefully by mid/late March. Keep well and keep safe.

Best wishes for now.

Ralph Lomas

Bill has published and lectured extensively on many aspects of the Great War for over 40 years. He has a particular interest in the work and performance of the Territorial Force.

He has recently retired as a member of the academic staff of King’s College, London, at the Joint Services Command and Staff College, Shrivenham. He has for many years led staff rides of senior British and international officers to the European battlefields of the First and Second World Wars.

Any study of the Italian Army on the Isonzo during the Great War reveals examples of incompetent leadership, the arrogance of a military supposedly subservient to a democratic government, appalling staff work, and treachery at home. Above all, however, it provides evidence of incredible bravery and endurance and, in the face of appalling adversity, remarkable group cohesion

The physical and climatic conditions in which the Italians and Austro-Hungarian forces fought were generally worse than those of the Western Front. The losses were unimaginable and the inability of certain Italian commanders to manage and learn from experience is bewildering. Despite the inhumanity with which they were treated - arbitrary executions, formal decimations, massacres of supposedly mutinous brigades by their own artillery - the fanti remained largely prepared repeatedly to hurl themselves against the Austrian defences.

There are tales of bizarre individuals such as the Italian poet-pilot who dropped his own poems instead of bombs on the Austrians; of how only hours after the capture of a mountain peak on which over 25,000 Italians had been killed and on which Austrian shells continued to fall, Arturo Toscanini conducted a band playing patriotic tunes; and of how, abandoned by his own comrades thoroughly irritated by his constant political exhortations, no more might ever have been heard of Benito Mussolini. There are instances of command relationships which were toxic to the point of treachery, and of inspired tactical leadership by individuals who rescued potentially disastrous situations.

Set amongst the incredible majesty of the Julian Alps, the verdant beauty of the Friuli Plain, and the sometimes torrential waters of expansive rivers, the first eleven Italian offensives were spread between June 1915 and September 1917. Characterised by their extreme brutality they were launched by hopelessly undertrained forces whose regimental soldiers could barely understand each other, against a polygot army whose almost sole unifying feature was its disparate soldiers’ hatred of the “treacherous” Italians.

With the intent of offering some insights to the conduct and character of the campaign as a whole, Bill Mitchinson will consider the eleven battles within their strategic and tactical contexts.

Topic: Zoom Meeting

Time: Feb 12, 2021 07:45 PM London

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83413647642?pwd=V1FObElRcEhEVEV5T1cvamRtRTVDUT09

Meeting ID: 834 1364 7642

Passcode: 324521

The Royal Army Medical Corps and other healthcare professions The overlooked dispenser and the diary of one who served

Before the Great War, the medical provision available to the general population was centred around their local chemist. Here they could discuss their problem and obtain a wide range of products and medications. The chemist that provided this service was knowledgeable, local and accessible. What was sold over the counter would be largely unrecognisable to modern eyes.

Pharmacists of all grades and training were caught up in the enthusiasm to volunteer for service in August 1914. Commissions in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) were restricted to those individuals with a medical degree and to Quarter Masters, who were often elevated to the position through the ranks1. As an emerging medical profession, pharmacists were keen to establish a role for themselves within the existing Army Medical Service framework. The highly trained pharmacist was denied a RAMC commission and many opted not to join and served as an officer in other services, rather than as a non-combatant ranker.

Pharmacists of all grades and training were caught up in the enthusiasm to volunteer for service in August 1914. Commissions in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) were restricted to those individuals with a medical degree and to Quarter Masters, who were often elevated to the position through the ranks1. As an emerging medical profession, pharmacists were keen to establish a role for themselves within the existing Army Medical Service framework. The highly trained pharmacist was denied a RAMC commission and many opted not to join and served as an officer in other services, rather than as a non-combatant ranker.

To add to the integration dilemma, the RAMC was also a male only organisation; females even when qualified as doctors, were excluded initially from service. Pharmacy had encouraged women to become pharmacists and they would have qualified for enlistment in all ranks. These gender problems were not to be resolved in 1914 as other pressing issues prevailed. This article sets out to provide an overview of the chemist role within local healthcare pre-war and go on to highlight how the roles of one of those professions, dispensers, developed within the Army Medical Services. In doing so it will give perspective and appreciation to the war service of our subject James Alfred Griffiths, a pre-war Boots dispenser, as recalled in his diary. He enlisted on the 13th August 1914 and went to serve initially on the Hospital Ship Oxfordshire

The need for dispensers

At the outbreak of the Great War the RAMC placed an announcement in the Pharmaceutical Journal for volunteers to fill the vacancies which they had for dispensing chemists2. It read:

‘In reply to inquiries which are being received from pharmacists who are desirous of taking service as military dispensers during the war, we are enabled to state that the conditions of such service are laid down in a special Army Order issued this week, dealing with the ‘enlistment of civilians for temporary service during the war. Men enlisted under this Army Order must not be more than forty years old and enlistments will be for one year, or if the war lasts longer, for the duration. We are informed that the services of 150 dispensers will be required, and that not more than fifty of these will be expected to serve with any expeditionary force that may be sent out of the country’.

These men were quickly recruited and sent to Ash Vale, Aldershot, the future home of the RAMC, for their initial training. James was one of this initial batch of recruits. This period of training was to induct them into the military and specifically into the role of the RAMC. James’ diary for 1914 doesn’t exist so we do not know how he felt about his training. Although a trained professional in his own right, he would have been given training in first aid, stretcher drills, basic field-craft and hygiene, plus physical fitness. In essence, if his role had not been pre-determined he could have for filled any number of medical vacancies.

Dispensers were required to comply with changes in the law and professional accreditation from which the services were not exempt. The services had to comply with legal requirements for the dispensing of drugs, principally the 1868 Pharmacy Act. The increasing size of the armed services also necessitated that those involved with dispensing and ordering medications knew the products, procedures and special requirements such as safe storage of drugs; in the short term, it was advantageous to recruit qualified individuals rather than train in-house. The pre-war pharmaceutical industry bears little resemblance to our modern practice.

Chemist shops, or apothecaries, were numerous and family run. The larger chains such as Boots were beginning to establish themselves across the country. Types of medication fell into two general categories, the traditional and herbal remedies made in Britain and the modern pharmaceutical proprieties predominately made in Germany, by companies like Roche and Bayer. The types of product available to buy over the counter was extensive as people generally self-medicated. Epsom salts and castor oil were used as purgatives, milk of magnesia for indigestion and various remedies derived from iodine were prescribed for “internal disinfection”3. The chemist shop also sold and prepared all dressings for wounds, made poultices4, supplied bandages and splints.

The 1868 Pharmacy Act separated drugs into two schedules. The First Schedule included many poisons which the chemist had to record in a Poisons Book. Legislation, following several prominent murders, had removed arsenic5 from the shelves but it was still available and popular as a tonic and painkiller. Other poisons for sale included strychnine which was used as a circulatory stimulant, and potassium cyanide. All these remedies could only be sold if the purchaser was known to the seller or to an intermediary known to both. The Second Schedule included opium and all preparations of opium such as laudanum. Also available over the counter was cocaine6.

Following the 1868 Pharmacy Act, it became a requirement that only suitable individuals could produce and sell over-the-counter medication. The Pharmaceutical Society took over the responsibility of registering individuals who had undertaken either a major or minor examination. The RAMC only wanted men with the minor qualification to act as dispensers, who would be enlisted as privates. Holders of the minor certificate would have completed an apprenticeship attended college, and taken exams in chemistry, botany, dispensing and other subjects.

The six-week induction course at Ash Vale prepared the civilian for service in the RAMC. One recruit detailed the course as mainly drill and keep fit and getting use to field conditions. The dispensers he felt were given far more guard duty than those going on to be stretcher bearers7. The instructors may have appreciated that on the completion of the course and in accordance with their civilian qualifications and responsibilities, the dispensers would be quickly promoted to corporal.

The newly recruited dispenser quickly found themselves in a crucial position within the medical logistic chain. With a keen understanding of the drugs, equipment and clinical need their expertise was quickly recognised and promotion came quickly. The role of dispensing sergeant was established. It was not uncommon for further promotion to the rank of Quarter Master Sergeant Major (RQMS) the second most senior non-commissioned rank to be held by former dispensing chemists. In between the political strategic decision making and the tactical resupply of soldiers on the fighting lines lies the operational or theatre level of the logistics of war. It was into these medically strategic bases that the dispensers were deployed. Base hospitals, home and abroad, ports, casualty clearing stations, railheads and anywhere there was a concentration of medical services. In the early stages of the war, they were also pivotal to the classification and distribution of medical supplies recovered from the retreating Germans8.

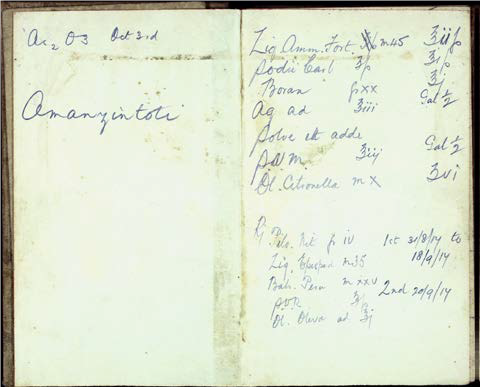

The dispenser became an integral role, initially in the sphere of their own civilian capabilities and experience but quickly learning and adjusting to the needs of the service. The specific competency would be in terms of medication supply and production. It should be remembered that many medications had to be made by the dispenser, hence the James crib notes in the front and back of his diary.

(Fig.2).

Alongside the date October 3rd (1915) is the chemical equation for Arsenic Trioxide. Arsenic compounds were, and are still, used therapeutically. In this instance it probably refers to Salvarsan, the drug then used in the treatment of syphilis.

Amanzimtoti is not a drug but a town near Durban, South Africa where he had a family friend and James was to visit her when his war took him to East Africa.

On the left-hand page: The formulae on the right are for external use, probably as muscular pain relievers or similar and makes two quantities, one to be used after the other (on dates given). The symbols used denote the old Greek apothecary system used before, Imperial and metric9.

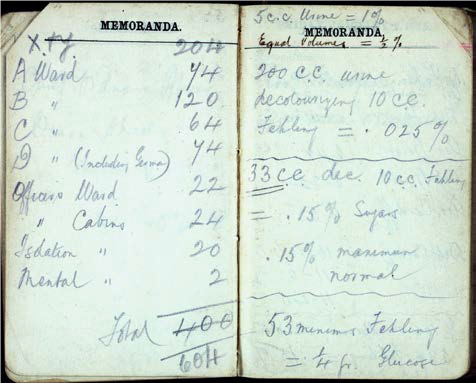

The dispenser’s specific role was determined where in the logistical chain they were located. James Griffiths was posted to the Hospital Ship Oxfordshire, the first ship to be converted for the role in the Great War. James doesn’t record mundane everyday details. He reserves any comments for what he considers noticeable events. Occasionally, as on a trip to Dublin, he would state that he was “ashore in the quest for supplies”10 or he would comment on meeting old Boots’ employees (performing a similar role) when ashore looking for stores. The second crib sheet again gives a comprehensive over-view of his responsibilities, see Fig 3. On the left-hand side are James’ ward list detailing the number of patients and their location aboard ship. A very precise man in his recordings as befits a pharmacist, the ship initially must have been for 400 and X+Y were added at some point bringing the total to 604. James, as part of the quartermasters team, would require to know how many patients they would potentially be treating, the duration of each voyage and when they can re-stock. He also in his jottings gives contact details as to where he can obtain medical stores for instance “The Chief Ordinance Officer, Orion Sheds, Cherbourg”.

The formula on the right-hand page (Fig 3, above) is to do with making a special solution as to test for sugar in urine in diabetes mellitus, before the advent of our modern dip-stick test12. James Griffiths dispensing role was specific to his hospital ship and would require a high degree of personal initiative.

Cox (2017) details several letters “from the front” which give a different insight into the wider dispenser’s role:

The maintaining of stock levels and all the correspondence involved was a large task for the dispensary. The chief dispenser wrote that they used vast quantities of tinct of iod . BP (tincture of iodine), hydrogen peroxide, acetosalicylic acid13, gauze, and absorbent wool. In addition, there were prescriptions from the twenty medical officers, and they also had to make and fit splints14.

This goes on to give a more detailed account of the Dispensing Sergeant’s role later in the war when established in a hospital setting as related by a Medical Officer:

It was suggested that all supplies had to go through the dispenser and if you wanted an appliance or instrument, you must get it from the dispenser on loan. If however the dispenser was inclined to be unpleasant, he could disinter Army Orders, which forbade anyone from ordering anything but a purgative pill or any instrument except their own. The writer commented that the dispenser probably spent more of his time with the commanding officer, than anyone else did in the place. Also, that the commanding officer was held financially responsible for drugs or instruments which were not accounted for. The dispenser therefore had many opportunities to lodge complaints against the prescribers.

The dispenser needed to be familiar with the procedures of indenting for all surgical instruments and know the intricacies of every army form. Finally, he described a typical working day:

It was busy in the morning, and evenings were generally quiet. The army dispenser was ‘fairly free of his own domain’. There was the occasional parade, or kit inspection. Everybody – the medical officers, the matron, the sister and the nurses – were on friendly terms with the dispenser as ‘he could always do any of them a service.

The role of the dispenser within the RAMC undoubtably expanded as the war progressed and became embedded within the logistical process. To ensure the efficiency of the system as the number of trained dispensers increased they came to populate all RAMC units all the way down to the smallest, the Field Ambulance. Initially the men were recruited for their civilian experience as to comply with legislation. Very quickly the scale of the war increased and medical logistics became imperative to enable the services to deliver one of the moral components of war, that of providing care for the injured. The dispenser became an integral part of the Quarter Masters team because he controlled the drugs, the surgical instruments and appliances. That responsibility was a heavy burden as at times, supply, maintenance of stocks, repair and sterilisation of instruments could not always be guaranteed. New medical/ surgical treatments also required the dispensers to keep their knowledge up-dated and have an active dialogue with Senior Medical Officers, their Commanding Officer and colleagues working at different levels within the army’s hierarchy. An effective dispenser was an asset; an inept one would create a considerable logistical headache.

James Alfred Griffiths

James was born in Wellington, Shropshire in 1880. In 1901, twenty-year-old James moved to Streatham and was employed as a chemist’s assistant. By 1906 James had moved to Exeter where he was married. He lived above another chemist’s shop run by John Tighe. At some point James started working for Boots the Chemists, fulfilling a relief role and so he regularly moved around the south of England, resulting in him having three daughters all born in different towns. James enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps as No. 9060 in August 1914 and after training started his war service on hospital ships from October 1914. His family returned to Barnstaple where they stayed for the duration. James kept a daily diary throughout the war until he completed his service in the spring of 1919. It is at this point that the diary stops. James returned to his family in Worcester in 1921.

James Griffiths sat cross legged 5th from the left. A picture taken at Ash Vale presumably of the 50 dispenser recruits plus trainers. Note that many do not have a RAMC badge on their cap, including James Griffiths

References

1 The commissioning of Pharmacist was a contentious issue and the profession lobbied Parliament to set up an Army Pharmaceutical Corps but to no avail. See Anderson, S.C. ‘Pharmacy and the Great War: The ‘Anti-microbe Corps’, Gas Masks and ‘Forced March’ Tablets’, Medical Historian, (2017) 27: 3-19).

2 Anon, ‘Pharmacists as Military Dispensers’, Pharmaceutical Journal 93, (8 August 1914), 218.

3 G. Heath and W.A. Colburn (2000) “An evolution in drug development and clinical pharmacology during the twentieth century” Journal of Clinical Pharmacology: 40: 918 -29.

4 Poultices. Prior to antibiotics, boils and swellings of the skin had poultices applied externally. They consisted of a mixture of bread, bran or kaolin mixed with boiling water, spread on gauze and then applied to the infected area.

5 The Arsenic Act 1851. All Arsenic solutions for human treatments had to be coloured by soot or indigo as to be more readily identified.

6 Anderson, S.C. (2011) ‘Drugs and War: ‘Useful presents for friends at the front,’ The Pharmaceutical Journal, 287, 7685, 742-7

7 Cox, N. (2017) “Frontline Pharmacy: letters from the First World War 1914 – 1918 Pharmaceutical Historian Volume 47, Number 3, September 2017 pp 66-69(4)

8 Medical stocks were left under the Geneva Convention which both sides adhered to. German pharmaceuticals were prized and made-up deficiencies in British stocks. For example see W.G. Macpherson et al (1923) Medical Services: diseases of the War Vol ll 10,000 doses of German made Salvarsan (the treatment for venereal disease) was liberated and shared out, there was no Allied alternative product at that time p. 148

9 Top formula Strong solution of ammonia 45 minims 2.5 fl.oz Sodium carbonate 0.5 drachms 1.5 oz. Borax 20 grains 1 oz Water to 3fl.oz. 1.5 gallons. Dissolve and add Spiritus Vini Rectificatu 3 fl.oz 1.5 gallons (alcohol) Citronella oil (fragrance)

10 minims 6 drachms. Bottom Formula Pilocarpine nitrate 4 grains Solution of Epispasticus 35 minims Balsam of Peru 25 minims SVR (alcohol)0. 5 fl.oz Olive oil to 1 fl.oz. Epispasticus is also known as ‘blistering liquid’, works like chilli paste, hot! 10 Griffiths Diary. Ashore in Dublin 25th June 1915 after embarking 694 patients.

11 McGreal. S. (2008) “The War on Hospital Ships 1914 – 1918” Pen and Sword, Barnsley approximates HS Oxfordshire to have 560 beds. James Griffiths records in his diary returning from Le Havre 3rd July 1916 with 1397 patients on board.

12 Fehling’s test comprises 2 solutions, No.1 was a copper sulphate solution, no.2 was potassium sodium tartrate. The two were mixed then boiled in a test tube with the urine sample. The copper sulphate (bright blue) turned brownish in the presence of sugar. The test was named after a German chemist, Hermann von Fehling.

13 The new wonder drug aspirin.

14 Cox, N. (2017) “Frontline Pharmacy: letters from the First World War 1914 – 1918 Pharmaceutical Historian Volume 47, Number 3, September 2017 pp 66(4) 69(4).

PoWs and the Queen Victoria Jubilee Fund Association

For an article on this curiously named organisation and its work in Switzerland tracing British PoWs, see Terry's article on this link - click here

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

This is the section for the newsletters for 2021.

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Chairman’s Comment

The WFA at the eleventh hour managed to arrange, via the DCMS, to lay a wreath on behalf of all members on 11 November at the Cenotaph at 11am.

It was arranged that there would be just five military officers and ten WFA members in attendance. John Chester, Chair of the Spalding and South Lincs Branch, who has been Parade Marshal on 11/11 since the retirement of Les Carter in 2011 was to lay the WFA wreath. He was accompanied by a group including WFA President, Gary Sheffield and Chairman, Tony Bolton. Guest Justin Maciejewski DSO, MBE, Director of the recently reopened National Army Museum; Rev Canon David Parrot, Chaplain to the City of London Corporation. Branch Chairs Kathy Stevenson, London; Neil Pearce, East London and Barbara Taylor, Thames Valley also London Branch member Nick Lucas.

The group assembled at the Guards barracks and were advised by GSM Stokes of the arrangements for the simple service that would take place.

Shortly after the group were marched down Whitehall and placed, sensibly distanced, beside the impressive memorial of the Cenotaph. The bugler played the Last Post and John Chester laid the wreath.

At the same time in Ypres at the Menin Gate there was also a very low-key ceremony in which only four wreaths were laid. This was the first time since the WFA’s founding in 1980 that they were unable to lay a wreath. See more on these events in the next Bulletin due out by Christmas.

This coming Friday we have, courtesy of Trevor Adams, another zoom talk, see details below to log on etc.

As to re-opening meetings we are still in the dark whilst news of vaccines etc offers hope for maybe Spring/early summertime.

STOP PRESS! News just in from our digital dept that the WFA YouTube channel has just hit the 5000 subscribers mark. We get quite a lot of ‘metrics’ from YouTube - just one of these is this “In the last 365 days, the channel got 293,111 views.”.

WFA membership shows a strong upward trend due to online activities. November tends to be a big month for new people joining and Sarah Gunn at the office is reporting big numbers joining so far by end of this month. This ongoing to date in December. Looking at the broader picture of total membership since the start of the Covid pandemic, in March this year membership stood at 5643. As at the end of 6th December it stands at just under 6000.

Ralph Lomas

We will remember them

Zoom meeting 11 December 2020 7:45 pm

To join the Meeting, click on:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84275931811?pwd=QnU5UmJ5dEx4dU51dC8xUk1PSG5IUT09

Meeting ID: 842 7593 1811 Passcode: 802440

John Crowther – “Just names on a memorial?”

John is a retired engineer and a Methodist lay preacher. He was at school in Belfast (with Trevor Adams) and then read civil engineering at UMIST. He worked all his career for an engineering consultancy near Chester. He lives on the Wirral. In early 2018, John sought help from Trevor and a local Wirral historian, Jenny McRonald, to find out something about the twelve names on the memorial plaque in Heswall Methodist Church. None of the families were believed to be still in the area. The results of John’s project were presented by him on Remembrance Sunday 2018 to the service in Heswall. His talk to us will be about what was discovered about the twelve names, from a starting point of total ignorance about their stories!

The Other Unknown Warriors

You don’t think about things sometimes because they have always been so, Britain has an “Unknown Warrior” buried in Westminster Abbey, probably called by most people - an “unknown soldier”, but he could be from the Navy, Air Force or Army hence he is a “warrior”. All other nations have an “unknown soldier” but New Zealand would perhaps disagree with that comment! 2020 is the hundred years anniversary of the Cenotaph being unveiled in London and the burial of the “unknown warrior”.

Around fifty countries now have unknown soldiers and France likes to think they were the first to honour their men in that manner, but due to several hiccups they were not. Following a victory parade at the Arc de Triomphe in late 1919, they announced that they would place a body in the Pantheon – home to bodies of French greats such as Napoleon, unfortunately the French public were not keen on that location so the Arc de Triumph was then chosen. Eight bodies were brought from battlefields where the French fought and a veteran from Verdun was allowed to pick which coffin would go to the memorial, but, he didn’t as he was found to be drunk, so a second man was chosen for the job. The other coffins were buried in Faubourg-Pave. Second problem was that the tomb was not ready to receive the coffin so it was taken to the top of the Arc until all was ready.

The planned wreath laying went ahead with the higher ranking first, followed by the common people. Not until early 1921 was the tomb ready and the coffin was buried with medals including one from the USA. An eternal flame burns on the tomb.

Belgium has its soldier in the Congress Column and was placed there late in 1922. Five bodies were brought in and then one was chosen by a crippled veteran. In 1921, Italy also decided to have an unknown soldier, but it was slightly tricky as they had twelve battlefields to choose from and Caparetto was a problem as they knew that they had shot some of their own men there. One in every ten men were shot because things had not gone well, so it seems.

A mother who had lost her son was allowed to choose which body would go to the memorial in Rome, the so-called Wedding Cake! Real name the Vittorio Emanuele II monument, of course, the tomb is guarded 24 hours. The other bodies were buried in a nearby cemetery. Once you get to the countries taken later by Russia, that is Rumania and Poland things got difficult. Rumania, as it was back then, had its site destroyed by the Communists in the fifties, the body must have been saved as with the fall of the Russian state it was returned to the site and now has a guard of honour. The Rumanian soldier was awarded a US medal but as yet we don’t know why.

Poland had its tomb in what was the Saxon Palace in Warsaw, issues with Russia and then Germany meant both countries were unpopular. Surprisingly when Germany destroyed the area during WW2 they did not destroy the site of the unknown soldier and it now has a garden with it.

Germany also had a memorial, Neue Wache in Berlin but it ended up in the East German part after WW2 and the Russians repaired it after we British had bombed the area. They included a victim of the Nazi camps in the site. Because of how Germany was made up during the Great War period the Bavarians decided on an unknown soldier memorial of their own, but this does not have a body. Surprisingly Australia did not decide upon an unknown soldier memorial until 1993, Canada until 1997 and New Zealand until 2002. Australia had a body from the Villers Bretonneux area the memorial is in Canberra.

Canada wanted a body from Caberret- Rouge Cemetery. Sadly, the Canadians have had problems after the memorial was placed at the National War Memorial in Ottawa in 2000. Youths were caught urinating on the memorial so guards are now placed to stop this disrespectful behaviour, then one of the guards was killed by an armed gunman.

New Zealand too had issues to deal with, in their case environment protesters. Finally the go-ahead was given and they got their body. On the 86th Armistice Day, 2004 he was laid to rest in Wellington, his body taken from Caterpillar Valley Cemetery.

John Chester

Special Poppy to Remember African-Black Soldiers

A poppy is available to remember African black soldiers who fought in WW1, these can be purchased at www.blackpoppyrose. org. The main idea is to get the children of these men to take an interest in their history as well as to remind us that men of all colours and religions fought along-side us during the war, doing their part for a war they would not benefit from.

Frank Smith Brooks

John Hartley emails… I read, with interest, the article about 2nd Lt Frank Smith Brooks. He was one of the many men commemorated on Stockport area war memorials that I researched some years back for my now defunct website “More Than a Name”. He’s commemorated on two civic memorials - Bramhall and Stockport - together with the memorial at St Mary’s Chuch, Stockport and the Manchester University one. My original website write-up on him, which adds to the UTL article, is now reproduced on the Cheshire Roll of Honour website: https://www.cheshireroll.co.uk/soldier/?i=1798/ second-lieutenant-Frank-smith-Brooks

Frank was born in Northenden on 8 August 1892, the eldest child of Arthur Percy Brooks and Edith Brooks. Arthur was a solicitor and was in partnership with another lawyer. They practised as Smith and Brooks with offices at St Peters Chambers, 39 St Petersgate, Stockport and 12 Exchange Street, Manchester. When the 1901 Census was taken, the family was living at 186 Northenden Road, Gatley. Frank now had two siblings - 4-year-old Alice and Bernard, just a few months old. When War was declared, the family had moved to Cheadle Hulme and was living at “White Cottage” on Bramhall Park Road. They later moved to “Redcot” on Bramhall Lane.

Frank had been educated at Stockport Grammar School and was studying law at Manchester University. He had also been articled to the family practice. He applied for a commission on 27 November 1914, stating he was a member of the Special reserve with the 4th Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment. When he became a 2nd Lieutenant, he was posted the 20th Battalion and took command of No. 14 Platoon, in “D” Company. The Battalion was the fifth of the “Pals” units raised by the Manchester Regiment in the autumn of 1914 and some details of their recruitment and training can be found here. He left for France with the battalion in November 1915.In early May 1916, Frank returned home for a brief period of leave but then returned to help with the Battalion’s preparations for the forthcoming “Big Push”.

An account of this attack, in which he was killed, is here. Frank’s friend, Lieutenant J W Ramsbottom, wrote to Frank’s parents:

“May I as an old associate of your son be allowed to express my sympathy with you in your great loss. He and I were in the same Company for over 12 months and I regarded him as one of my greatest friends in the Battalion. But with all of us, he was popular because of his cheery ways and his happy gift of looking on the bright side of things. We all miss him terribly and so can sympathise the more with you. But we are proud of him and those who died with him. I hear he was killed almost instantaneously and so would suffer no pain. He was leading his men across to the German trenches. He has been buried with his commanding officer and other brother officers in a grave in the German trench they died trying to capture and thanks to their efforts in the past and their example in the attack, it was captured.”

The father of one of Frank’s Bramhall friends, Frank Clarke, also wrote saying his son “must have been near Lt Brooks when he was hit as he and another officer rushed out and carried him into the lines”. To have been able to do this must mean that Frank had been killed only a few yards into No Man’s Land after he went “over the top”. The trench where Frank was originally buried was just south of Fricourt. After the Armistice, many of these small front-line burial areas were closed as the land was returned to civilian use. Frank’s body was exhumed and reburied at Dantzig Alley - itself a captured German trench - where his grave is now tended by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Dantzig ALLEY CWGC Cemetery

The village of Mametz was carried by the 7th Division on 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, after very hard fighting at Dantzig Alley (a German trench) and other points. The cemetery was begun later in the same month and was used by field ambulances and fighting units until the following November. The ground was lost during the great German advance in March 1918 but regained in August, and a few graves were added to the cemetery in August and September 1918. At the Armistice, the cemetery consisted of 183 graves, now in Plot I, but it was then very greatly increased by graves (almost all of 1916) brought in from the battlefields north and east of Mametz and from certain smaller burial grounds, including Aeroplane Cemetery, Fricourt, on the old German front line to the south of Fricourt village. It contained the graves of 24 NCOs. and men of the 20th Manchesters who died on 1 July 1916.

2nd Lt Brooks, centre of the photo

2nd Lt Brooks, centre of the photo

John Hartley has researched the lives and deaths of the men - and one woman - commemorated on the civic war memorials in the borough of Stockport, for the Great War period - nearly 3000 of them. He started his voluntary project in conjunction with the Local Heritage Library. It was intended that it would lead to a virtual war memorial for the borough but when the Library decided it was unable to continue with it, John launched his own website - “More Than A Name - the stories of Stockport’s fallen”. Early retirement meant he had much more time available for the project and it was substantially completed by 2008. It became a well-used resource for family and local historians, as well as local schools in their teaching of the War. The website no longer exists. A couple of years ago, it suffered a major crash and it was impractical and unaffordable to try and rebuild it. However, all was not lost. John had been in contact with the Cheshire Roll of Honour website - https://www.cheshireroll. co.uk/ - to pass on the research for them to also use. That website is gradually uploading the pages, along with their research into men commemorated on memorials throughout the county.

John is also the author of four Great War books, including battalion histories of the 6th heshires (Stockport’s Territorials) and the 6th and 17th Manchesters. He has also written a book about food during the War. Although no longer involved, he was a founder member of the In From The Cold Project which works with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to identify casualties of both wars who slipped through the net for official commemoration. To date, the Project has had nearly 6100 names accepted and a further 1200 are awaiting a decision.

A Great War Chaplain’s Story

Rev AE Acton 1889-1917

Armar Edward Acton was born in Galway, Ireland in 1889. His father was serving locally with the 1st Battalion Connaught Rangers. The 1911 census places him at a Divinity College.

Prior to enlisting in 1916, Reverend Acton was a Curate at Holy Trinity Church, Bury and he is recorded on the local memorial. Chaplain 4th Class is the lowest commissioned rank for the clergy and roughly equates to a Lieutenant.

The inscription on his headstone “Fatally wounded when visiting his men/Menin Road. Faithful unto death” would appear to be a comment placed by the family, suggesting that unlike other Church of England clergy, who were often tainted as staying far away from any fighting, Reverend Acton was at the front with “his men”. This criticism of C of E padres being distant and in the rear areas as opposed to Roman Catholic priests who were often seen in the front lines and were portrayed as very sociable was expressed by various commentators such as Sassoon and Graves(1)

Rev Acton’s military service prior to this action is not clear but in keeping with his inscription he must have been active and involved with the troops and their perils as he was Mentioned in Dispatches.

Action at the Menin Road

The 2nd Battalion Border Regiment were involved in the Second Battle of Passchendaele which commenced at 05.40 on the 26th October 1917(2). The Battalion was involved in a 20th Brigade, 7 Division attack. The battalion advance was in a South Easterly direction with the village of Gheluvelt on their left and the remains of Tower Hamlets on their right. D company was on the left, C company on the right and B “moppers up” and A company in support.

Following a creeping barrage both A and D company quickly began the advance but soon found themselves in extremely unsuitable ground full of craters and liquid mud. C company continued the attack but found themselves “advancing in mud up to their waste”, their officers becoming easy targets for snipers, the company was “almost entirely wiped out”. D company went to what they thought was dryer ground, going over the Menin Road before attempting to take pillar boxes which were holding up their advance. Again, most of the company was wiped out and they regrouped in a crater on the road.

Reverend Acton I suspect must have been with D company which ended up on the Menin Road. His injuries that killed him eventually on the 4th November 1917, ten days later were reported as from gas (Comment in the CWGC’s summary). The War Diary does not record any bombardment or gas attack. It is more than probable that gas might have been lingering in the craters that the company used for shelter. The Battalion was relieved the following day and was taken by motor transport to a camp at Blaringhem. The 7 Division did not know at the time but they were going from Ypres to Italy. The 2nd Border Casualties for the 26th October attack were:

Officers killed: 5, wounded: 2, missing 1.

ORs killed: 6, wounded: 174, missing: 126

Reverend Acton I suspect was one of the two officers wounded or possibly the one missing.

Gas poisonings takes some while and the sufferer can linger for a long time, as in this case ten days. He may, because of the high number of casualties and conditions not have been recovered and evacuated straight away.

His injuries must have been significant and prognosis poor as he was not evacuated to England. He passed down the medical evacuation chain to the military hospital complex at Wimereux. He passed away on 4th November 1917 and is buried in Wimereux Communal Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France. CWGC, Ref: - IV. L. 2.

Final Note. Holy Trinity Church in Bury is now a redundant Anglican church. A brightly painted reredos, was unveiled in 1987 as a First World War memorial, which may have commemorated Rev. Acton. Does it still exist?

Perhaps any member living in/near Bury could investigate?

Eric Hunter

References (1) https://www.ool.co.uk/blog/padres-priests- great-war/ (2) WO95-1655-1 War Diary 2nd Battalion Border Regiment.

Congratulations to Harry Carlisle for getting the Macclesfield Mayors Award

Harry comments: “I was very proud and honoured to have received such recognition but I must give great credit to all my colleagues whom I work alongside at the Cheshire Villages Great War Society. As a team we have staged 28 WW1 Memorial exhibitions over the past seven years, one of which was as far abroad as Norfolk”.

“Along with staging these exhibitions I have written five books on the fallen from North East Cheshire, and have also given talks at seven schools on the subject of the Great War. All of which have proved to be a busy work load, and for an 82 year old it doesn’t get any easier. To top this, I get a regular supply of enquiries from the general public on their relatives, who either perished or survived WW1, plus I am getting more and more on WW2”.