Articles

- Details

- Category: Articles

The Italian Farina Helmet

Terry Jackson

The "Farina" helmet was one of the early developments of the combat helmet in World War One. After the invention of gunpowder, the medieval helmet and armour lost their importance and disappeared. During World War I, the helmet was to be used again on the battlefield.

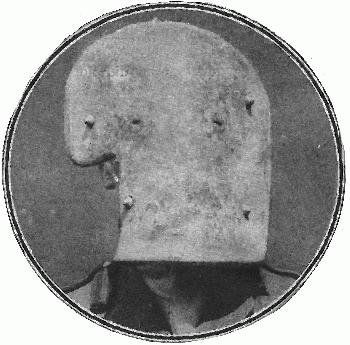

This form of helmet was first designed for use by sentries in forward positions as a protective alternative to the cloth Berroto cap and other forms of headdress used in the Italian army during the opening stages of the First World War. Made by the Milan firm of Elmo Farina, it was adopted on a wider scale of issue from October 1915 by the spearhead 'wire cutting companies'. These were specialist volunteer engineer troops who led the assault and cleared wire entanglements ahead of the infantry, vital tactical operations which required great courage and skill. The helmet weighed 2.85kg (6lbs 5oz), and would be worn over a padded cloth cap. In addition, the 'compagnie della morte' wore additional body armour (weighing 9.25kg - 20lbs 6oz), thick leather gauntlets, knee protectors, and carried specialist tools including wire cutters mounted on poles. It has been suggested that the helmet and body armour could be effective against rifle ammunition fired at distances down to 125 metres.

The helmet was designed and produced by the Engineer Ferruccio Farina, whose laboratory was in Via Ruffini in Milan. The name and address were written on an oval stamp inside the front brim of the helmet which also had the size in Roman numerals (I-II-III). The helmet was composed of three main parts painted with green-grey opaque non-glare paint. The shell was an oval metal-plate fixed by eight tacks; the fore brim was formed by four overlapping steel sheets fixed together by five tacks; the back brim was also of metal-plate and four centimetres high.

At ears-length there were other elements in plate metal and a grey leather liner with a metal buckle. The front brim of 12 or 8 centimetres distinguished the "high" model from the "low" model. The "high" model weighed 2250 gr. while the "low" model weighed 1850 gr. In the first models there was no ventilation system and so it was provided later via a plate shell outside the protection brims, permitting better air circulation. These models with ventilation had both the versions with "high" brim and "low" brim. The problem of ventilation was solved when a crest similar to the "Adrian" helmet was adopted to cover a hole on the top of the shell. This change was made on the helmet of both models.

There was no standard padding and initially the helmet sat on the soft cap which was worn back to front.. Later, cloth head-support was stuffed with horse hair and cotton wool. In some cases, two pieces of natural rubber were fixed inside the front brim to improve helmet stability. In spite of the attempts to improve stability of the helmet, the "Farina" helmet remained uncomfortable and heavy.

The production ceased with the subsequent distribution of the 1915 French ‘Adrian Model’ to Italian forces.

- Details

- Category: Articles

General Louis Adrian and the French Helmet

Terry Jackson

In 1914 when the nations of Europe went to war, the institutions of the military powers embraced all the modern techniques available and they continued to adapt them as the conflict progressed. It was the first war in which fighting was fully pursued on land, on and under the oceans and in the heavens above.

However, the largest element of the nations, their men in the armies, had little modern personal equipment other than their rifle and other ordnance. In particular headgear was generally no more than a cap or, in the case of the Germans, a leather helmet.

On the Western Front by 1915, the opposing forces faced each other below ground level or behind breastworks, where the water table was near the surface. Whilst, for most of the time, the Germans were content let the Allies risk their lives trying to regain French and Belgian territory, when the antagonists were in their opposing trenches, the most vulnerable part of a soldier’s body was the head. It was liable to be shot at if inadvertently exposed above the parapet or suffer a shower of falling metal from the sky above.

The first attempt to alleviate this hazard came from the French. Loius Adrian, a French officer, was known for his concern for his men’s welfare. In early 1915 he developed a metal skull cap (calotte) that could be worn under the kepis and kept in place by a sweat band. The popular belief is that he had discovered a poilu wearing a metal soup bowl on his head for protection. However, the facts are likely to be that after it was issued, some soldiers used it as a drinking vessel.

It. was made of stamped soft steel, 5mm thick, and could be held in place by a sweat band. Adrian had been involved in in the logistics of army equipment and after the relative success of the calotte, 700,000 having been issued, he was empowered to design a protective helmet, France being the first nation to do so in bulk numbers..

By the spring of 1915 after the relative success of the calotte, Adrian started his work. Seeking a national connection, he based his design on the existing fireman’s helmet. This was a bowl with a rim and a crest on the crown. It was worn by the urban pompiers, well known in the cities.

The calotte

The calotte

The design was a bowl with a median crest and a brim. On the forehead a relative unit symbol was pinned-crossed cannon, grenade etc. It was made in three sizes with an appropriate liner with vertical flutes to give some ventilation and keep the shell off the surface of the head. The brim was in two pieces- front and rear, crimped level with the ears. On the top of the dome was a crest held on by rivets. Beneath this was an open slot 40mm long, 10mm wide, to help ventilation. It had a leather liner, flower shaped, which could be adjusted by a chord. An adjustable chin strap was attached to the sides. It was issued in 3 sizes and production began in mid-1915.

Adrian helmet

The helmet was manufactured by Compteurs et Matériel D’Usine, Rue Claude de Veilefaux, and the firm August Pepyon, both of Paris. 3 Million were produced by September 1917. The former could make 7500 per day using 200 press machines with 8 mechanics in the tool room. The helmet was made of mild steel 0.277 inches thick with a tensile strength of 62,000lbs per square inch. It did not shatter which avoided steel being carried into the head. However, no attempt was made to alleviate the thinning of the crown caused by the stamping and it only had half the resistance to a revolver shot compared to a Brodie helmet. It had not been tested ballistically before issue. It was therefore weaker, but lighter than the British model. Its main weaknesses were the brims, being in two pieces and the number of rivets and joints which were prone to fail if hit with any force. Nevertheless it became a symbol for the common soldier.

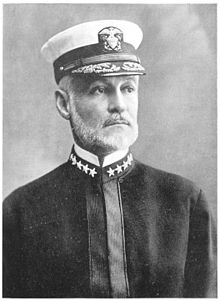

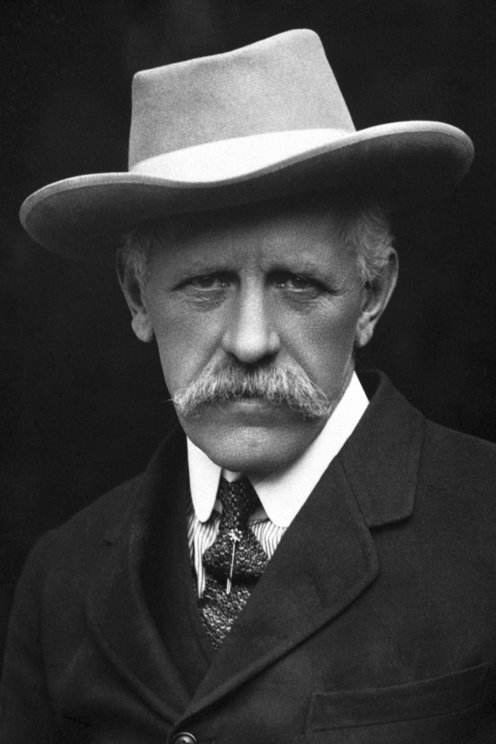

General Louis Adrian (photo right) was born in Metz in 1859 but moved away during the Franco–Prussian War and studied engineering and applied engineering at the École Polytechnique in Paris. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 3rd Arras Regiment. In 1885 he was a captain at Cherbourg, constructing barracks and coastal defences. He was posted to Madagascar where he planned facilities for the Army in what was a strange environment. He was responsible for improving roads, building bridges and lightweight barracks. He suffered from the effects of the climate and was repatriated to France in December 1885. That month he married Marguerite Pigeon, niece of the Priest of Genȇts.

In 1904, despite making enemies, as he dealt with fraud and corruption by army suppliers, he was awarded the Légion D’Honneur in 1912 for removing the contractors of military beds and making a state body responsible. His health caused him to retire in 1913 and he settled in Genȇts. He subsequently spent some time in Venezuela and developed a portable shed for use by beef cattle farmers.

The army reinstated him in 1914 as the Supply Officer and he became the Assistant Director of Stewardship for the Ministry of War (Clothing and Equipment) for the French Army. This involved clothing and equipping the rapidly expanding army. He acquired 4 thousand tonnes of cloth and wool from Lille in October 1914 just prior to its occupation by German forces.

Adrian also acquired sheepskin jackets during the bad winter of 1914/15, made soldiers’ back packs easier to carry and insisted on the provision of strong boots. His work on ’cattle-sheds’ enabled soldiers to be housed in barracks when out of the line, instead of using cold and wet tents. He organised construction of these sheds by 200 companies with a production rate of up to 50 per day.

Adrian persuaded Joffre to allow the production of skull caps in February 1915 and by the spring some 700,000 had been made. By the end of April 1915 the Japy factory had agreed to provide 529 thousand, but they had only made 141 thousand. Adrian pushed them so that by September they were producing 52 thousand helmets per month. Adrian indicated that having received its baptism of fire, it preserved the life of a considerable proportion of men to whom it had been allocated. Initially the soldiers had been unimpressed, but gradually accepted it as part of their standard equipment.

By 1917, head wounds were 22 percent of all wounds but only 50 percent were fatal. Some 15 different companies made the Adrian helmet and others made helmets exclusively for officers costing 20-25 Francs. However they were of poorer construction and often shattered if hit by shrapnel. By the end of 1916, 7 million had been made for other nations at a cost of 6F each. Italy had 1.5 million, Russia 340 thousand, Belgium 208 thousand, Serbia 123 thousand, Romania 90 thousand and Holland 10 thousand. By 1918, 20 million had been made.

On 18 December 1918, a Decree granted officers and soldiers a ceremonial Adrian helmet with a plaque attached ‘Soldat de la Grande Guerre 1914-1918’ The Adrian like the Brodie helmet was improved during the inter war period and was still being used by the police after the Second World War. Adrian’s success created jealousy and accusations of corruption, which were rejected out of hand by the Government. (Photo right - Adrian's grave).

After the War Adrian continued to work, developing body armour, splash goggles, armoured aviation turrets and he studied solar energy. He was awarded the Grand Officer de la Legion d’Honneur in 1920. He retired to Genȇts in Normandy. He died in a military hospital in Val-de-Grace 8 August 1933.

A final anecdote is that after his fall from grace, following his part in the Gallipoli disaster, Churchill served temporarily as an lieutenant-colonel with the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers at Ploegsteert., He wore a Casque Adrian amongst all the Tommies, saying it provided more shade than the Brodie helmet and disguised who he was so he could get on with his duties…….

There are several books on helmets available to purchase. It is also possible to read on line the American Bashford Dean’s book, ‘Helmets and body armor in modern warfare’. Published just after the end of the Great War, it includes an appraisal of the attempts of the various nations’ to provide protection for their soldiers and the prototypes that were being considered for future conflicts). TJ

- Details

- Category: Articles

Terry Jackson

During World War One, the US Navy inflicted few losses on the German Navy - one definite U-boat plus others possibly mined in the huge North Sea barrage laid in part by the US Navy between Scotland and Norway. Also, few major ships were lost to enemy action - one armoured cruiser and two destroyers. However, the large and still expanding US Navy came to play an important role in the Atlantic and Western European waters, as well as the Mediterranean after the declaration of war in April 1917.

Most of the battlefleet stayed in American waters because of the shortage of fuel oil in Britain, but five coal-burning dreadnoughts served with the British Grand Fleet as the 6th Battle Squadron (US Battleship Division 9) tipping the balance of power against the German High Seas Fleet even further in favour of the Allies. They were also present at the surrender of the German Fleet. Other dreadnoughts (Battleship Division 6) were based at Berehaven, Bantry Bay, Southwest Ireland to counter any break-out by German battlecruisers to attack US troop convoys. Some of the pre-dreadnoughts and armoured cruisers were employed as convoy escorts between 1917-18 both along the coasts of the Americas and in the Atlantic.

All three scout cruisers of the 'Chester' class together with some old gunboats and destroyers spent part of 1917-18 based at Gibraltar on convoy escort duties in the Atlantic approaches. The destroyers were part of 36 United States destroyers that reached European waters in 1917-18. Many of them were based at Queenstown*, Ireland, St Nazaire and Brest, France. Their main duties were patrol and convoy escort, especially the protection of US troopship convoys. Some of the 'K' class submarines were based in the Azores and 'L' class at Berehaven, Bantry Bay, Ireland on anti-U-boat patrols 1917-18.

In 1917, the programme of large ship construction was suspended to concentrate on destroyers (including the large 'flush decker' classes’, 50 of which ended up in the Royal Navy in 1940), submarine-chasers, submarines, and merchantmen to help replace the tremendous losses due to unrestricted U-boat attacks. Some of the destroyers and especially the sub-chasers were deployed in the Mediterranean, patrolling the Otranto Barrage designed to keep German and Austrian U-boats locked up in the Adriatic Sea.

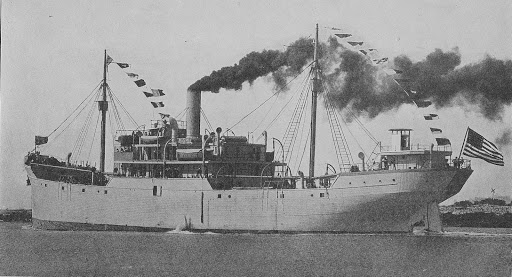

USS Melville

A month after the United States declared war, the first American warships arrived in Europe on 4 May 1917. The Germans had resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1917, leading to more than 800 Allied ships being sunk in a matter of months. Without escorts, these ships served as easy prey for the Germans. This warfare had reduced British grain stores to a critical three week supply. The Royal Navy urgently requested more destroyers for hunting submarines.

The destroyers’ arrival was due in part to the presence in England of an American naval mission headed by Vice Admiral William Sims (photo right). A few years before as Capt. Sims, he was President of the Naval War College at Newport. Appointed by the first Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), William Benson, together they anticipated a transatlantic naval war involving new challenges and technology. Ashore and in exercises of the “War College Afloat” they studied the role of the Navy in modern war.

By 1917, Benson anticipated a naval campaign in European waters that would require a naval headquarters in England. Sims, with established reputation throughout the Navy, proved the ideal officer for that mission. He travelled to London under an assumed name, in civilian guise, arriving on 2 April 1917 with the intention of establishing direct contact between the United States Chief of Naval Operations, the Royal Navy, and other Allied naval forces.

By establishing an office in England called the “London Flagship,” Sims and a select staff of officers and expatriate American specialists evaluated and passed Allied naval communications and intelligence to the Department of the Navy. Sims and his staff promoted American naval opinions when reviewing strategy with the British Admiralty. They challenged the Royal Navy’s anti- submarine method and insisted that supply ships should sail in protected convoys.

A trial convoy formed on 10 May at Gibraltar, and sailed to England without loss. The second escorted convoy, bound for England from Virginia, also arrived undamaged. After that, all supply and troop shipping was required to sail in convoys. By mid-June, the five American destroyers were escorting groups of arriving merchant ships into harbour. The convoy strategy overcame the German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign.

In the first month of American involvement in World War I, the U.S. Navy changed the strategic balance, not with its growing fleet, or daring operations, but through sound strategic thinking. The convoy system secured the passage of the American Expeditionary Forces to France along with vital supplies for all the Allies. America was becoming a world power with a first class navy.

German and British naval policies made it difficult for the United States to remain neutral between 1914 and 1917. However, the intermittent German employment of unrestricted submarine warfare posed the severest challenge because of the inability of a small submarine to observe traditional prize rules. Disputes over enforcement of the British blockade could usually be settled by legal means in a prize court. German actions, in contrast, were final and could result in loss of life. The ship had been sunk, and - given the geographical realities of the North Atlantic - often in conditions hazardous to passengers.

On 4 February 1915, Germany declared the waters around the British Isles to be a war zone in which ships, even those flying the flags of neutral nations and their passengers, would be at risk. America insisted on the right of its citizens to travel unmolested. A series of German attacks resulted in strong American protests and temporary modifications of German naval actions. The most famous incident was the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915 after the German government had published a warning in the New York press directed at residents of neutral nations sailing in ships flying enemy flags. There were 128 United States citizens among the 1,200 lives lost. In the face of the press and political storm that followed, the German government drew back and ordered submarines not to sink large liners, even those that flew enemy flags. This incident created a pattern reflecting the tug of war within the German government between those elements in the military anxious to exploit an effective weapon, and those seeking to minimize damage to relations with a powerful neutral like the United States.

There was another serious incident in March 1916, shortly after the Germans embarked on what could be called a “sharpened” submarine offensive. On 24 March, the cross channel steamer Sussex was torpedoed without warning and severely damaged; American citizens were among the casualties. Although the Germans denied responsibility for the incident, the protest by the United States government was sufficiently strong to bring about the so-called “Sussex pledge” on 4 May. German submarines would attack merchant ships only under prize or cruiser rules, not without warning. It was not until 1917 that a very few American flagged ships came under direct German attack, and some American lives were lost in them. Between 1 January 1915 and 31 January 1917, there were only three American fatalities.

Ferry "Sussex"

Germany’s failure to achieve favourable results in the Battle of Jutland, the long stalemate on land, and German naval assurances that unrestricted submarine warfare would force the British to make peace within a few months brought mounting pressure on the German government to sanction the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. The pressure was strong enough that, at the Schloss Pless Conference on 9 January 1917, it was decided to commence unrestricted submarine warfare as of 1 February. President Wilson responded by breaking diplomatic relations with Germany on 3 February. However, there was no state of war until German submarines sunk a number of American flagged ships in March. In at least three cases - the Vigilancia, City of Memphis and tanker Illinois - President Wilson considered German actions as “overt” acts of war, for they involved ships clearly identified as American. In some cases, ships were westbound in ballast, so there could be no question of contraband cargo. It is debatable how much weight Wilson gave to these sinkings in making his final decision to ask Congress to declare war against Germany in April 1917. Nevertheless, the clear offensive nature of these acts and lack of ambiguity - such as Americans traveling under a belligerent flag - provided a powerful justification for action by Congress.

The United States Navy embarked on a major building programme, which was approved by Congress in August 1916. New construction over a three-year period was to include ten battleships, six battle cruisers, ten scout cruisers, fifty destroyers, and sixty-seven submarines. It was, however, a fleet destined for a major naval encounter, which did not reflect the necessities of the naval war in Europe. The Navy at the time had only forty-seven destroyers in commission, the type of warship most needed in the struggle against submarines. Upon entering the war the Navy suspended the 1916 program and prioritised the construction of destroyers, building 273 of these ships. Few of these destroyers, however, ever entered wartime service.

A wooden freighter

Rear Admiral William Sowden Sims who had been dispatched to discuss possible cooperation with the British even before the United States formally entered the war, sought to convince the American government that the Allies desperately needed anti-submarine craft - preferably destroyers, but in practice any suitable craft was needed. This meant overcoming the concerns of the Chief of Naval Operations, Rear Admiral William Shepherd Benson saying that the loan of destroyers to the British would leave the American battle fleet unbalanced and not ready for future possible fleet action. Fortunately, the American government realized that the decisive theatre of war would be European waters, where destroyers, not battleships, were needed. The first tangible naval assistance to the British came in the form of six destroyers of the Eighth Division, Destroyer Force, Atlantic Fleet, which arrived at Queenstown, on the southern coast of Ireland on 4 May 1917.They were the first instalment of a planned destroyer force of thirty-six, a goal achieved by the end of August. The destroyer tenders Dixie and Melville were also sent to support the destroyers. The American destroyers worked under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, the British Commander in Chief, Coast of Ireland. Engaged first on patrol duties and subsequently as convoy escorts, these destroyers were probably the most important American contribution to the naval war. A large number of converted yachts later supplemented the destroyers’ anti-submarine work, particularly off the French coast. Admiral Sims was designated commander of US Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, and had headquarters in London, commonly known by its telegraphic address as “Simsadus”.

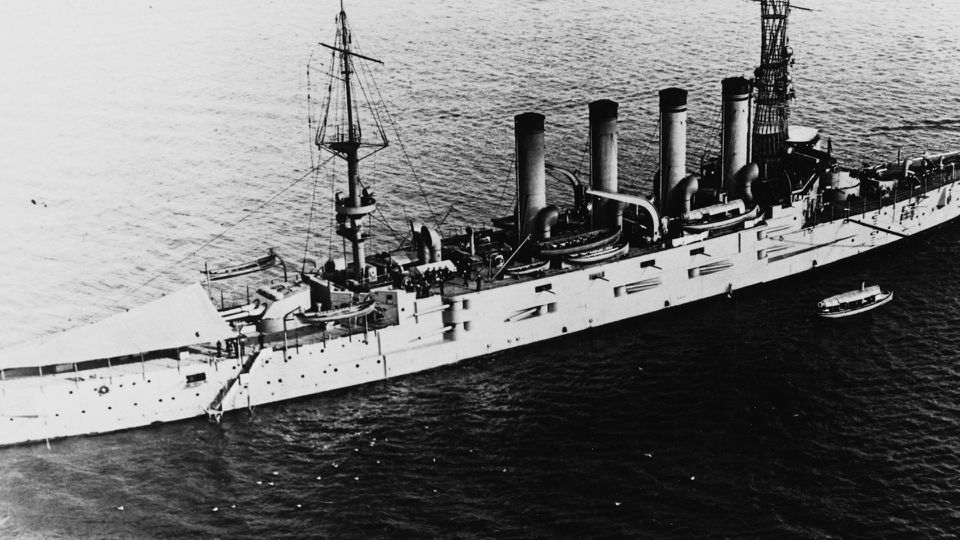

USS San Diego

The Americans did not deviate from their strategic point of view that the centre of gravity of the naval war was on the other side of the Atlantic. They might have been tempted to do so in the summer of 1918 when the German Navy sent large submarines to operate off the North American coast. The six U-cruisers eventually achieved a number of successes between May and October 1918, sinking ninety-three ships, more than half were American, but almost two-thirds were either sailing craft or small fishing vessels.

Convoys were for the most part unscathed. The most notable event was the sinking in July of the large armoured cruiser San Diego, sunk by a mine off Fire Island, near New York harbour. This demonstrated that the war had come to America's doorstep. Indeed, there was even a partial blackout of New York City for a period of time. Importantly, the US Navy did not recall forces from European waters, and reassured America's Allies that this policy would not change. Furthermore, the German Navy was unenthusiastic about these operations. The limited number of large submarines and the long transit times involved meant operations off the American coast were uneconomic compared to operations in European waters.

The prospect of a major naval battle similar to Jutland in 1916 may have receded, but could not be completely discarded. If such a battle ensued, the American Navy was understandably anxious to contribute with its most powerful warships. Consequently, Battleship Division Nine of the Atlantic Fleet, consisting of four dreadnoughts under the command of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman joined the Grand Fleet on 7 December 1917 and was designated Battle Squadron Six. The Americans, at British request, deliberately sent coal-powered battleships, as the British Isles had abundant sources of coal but had to import oil. The American dreadnoughts added to British naval superiority, although they never participated in the major fleet action for which they were designed. Later in the war, in September 1918, another three American dreadnoughts were stationed at Berehaven, Ireland, to counter a possible threat of German raiders in the North Atlantic. Once again, however, they never actually fired their guns in a hostile engagement.

The war against submarines required a different type of warship, one small and suited for escort or hunting duties. The American Navy developed craft commonly called “sub chasers”. These were 110-foot wood hulled vessels of seventy-five tons displacement, each armed with a three-inch gun and a few depth charges and powered by a gasoline engine. They were far less complex to build and operate than the larger craft and were therefore ideally suited for construction by smaller private yards. The Americans eventually built more than 400 of these ships. Unfortunately, they were far from ideal for their purpose as they were too slow to effectively escort convoys. Admiral Sims recognized their deficiencies, but made the best use of them possible. As he admitted to a French naval officer, he did so simply “because we have them.” The Americans placed great hopes on an innovative method of hunting U-boats with hydrophones or sound detectors. The sub chasers in theory would operate in groups of three. Two chasers would locate the submerged submarine by cross bearings while the third would execute the “kill” with depth charges. The British had experimented with hydrophones with indifferent results and the Americans were also disappointed with this strategy. The experiments in underwater detection continued after the war, leading to the development of ASDIC (sonar), widely used in the Second World War.

Sub chaser

The number of sub chasers in European waters steadily increased, as did the areas that they covered; by the end of the war, there were over one hundred in use. One squadron of thirty-six chasers operated from Plymouth in northern waters. Another group of chasers operated in the Strait of Otranto at the entrance to the Adriatic. This was a natural choke point through which Austrian and German submarines, operating from their bases at Pola and the Gulf of Cattaro, had to pass in order to reach the Mediterranean. The British, French and Italians were attempting to close this passage to submarines through a constantly expanding mine net barrage (the Otranto Barrage) patrolled by drifters and destroyers as ‘chasers’. Unfortunately, while the theory was fine, results were disappointing. The war ended without any chasers destroying a single submarine. The barrage was credited with two submarine sinkings: one submarine was ensnared in a net, and one was sunk by a mine.

The American effort in naval aviation was at least somewhat more successful than the Otranto Barrage. The rapid development of aviation was one of the notable features of the war, and the US Navy exploited its potential. The US Naval Air Service began operations at the British air station at Killingholme, near the mouth of the Humber, in July 1918 and eventually established four seaplane bases and a kite balloon station in Ireland. In France, there were six seaplane stations, three dirigible stations, and two kite balloon stations. Additionally, there was a large assembly and repair base at Pauillac, near Bordeaux, under construction at the time of the Armistice. In Italy there were another two seaplane stations on the Adriatic. Naturally this growth took time and accelerated in the closing months of the war. The numbers by then were impressive: 2,500 officers, 22,000 men, and over 400 aircraft. The Navy relied primarily on foreign-designed and foreign-built aircraft.

The lack of suitable aircraft slowed the development of a Navy and Marine “Northern Bombing Group” of land planes in northern France, whose mission was to bomb German submarine bases on the Belgian coast. The range of aircraft over the high seas was still relatively limited, but in coastal waters they were effective. This was especially true after German submarine commanders responded to the extension of the convoy system by moving closer inshore to attack ships after convoys had dispersed and ships headed to their final destinations. Because World War I aircraft could not carry a bomb load sufficient to sink a submarine, aircraft were perhaps most useful in harassing submarines and making it difficult for them to stalk ships on the surface or take up favourable firing positions. Naval use of aircraft therefore prevented losses rather than destroyed submarines.

The Navy also developed a more effective anti-submarine craft than the 110-foot chasers. These were the 200-foot, 430-ton “Eagle” Boats sometimes referred to as “Ford” Boats because they were built by the Ford Motor Company of Detroit. Over one hundred of these were ordered. Ford applied the industrial techniques of mass production to their construction when possible. A non-traditional ship builder like Ford, with yards on the Great Lakes (and thus far from the ocean) was a notable example of the industrial potential of the United States applied to the war effort. However, no ships were finished before the end of the war. The same techniques of mass production were applied to the building of standardized classes of cargo ships. One of the largest complexes of shipyards in the world was constructed on the undeveloped mud flats of Hog Island, near Philadelphia. There was also a large class of so-called “Lakers”; the “Lake” class of smaller freighters built in shipyards on the Great Lakes. Their size was limited by the necessity of passing through the Welland Canal in order to reach the high seas. Again, relatively few of these ships had entered service by the time of the Armistice.

The debate on instituting the convoy system began within the Royal Navy just as the United States entered the war. The British had already experimented with local systems. Extension of the convoy system proved to be slow, with the relatively ineffective patrol systems continuing at the same time. Convoys had their doubters in the American as well as British naval commands, and even the role of Admiral Sims, long credited with their adoption, is unclear. Nevertheless the United States was an invaluable source of anti-submarine craft, whether the craft were used on patrols or in convoys.

The American naval contribution to logistics was also great. By the end of the war there were over a million American soldiers on the Western Front, transported with only minor losses across the ocean. The American merchant marine did not have the large liners found in the European fleets, but the Americans were able to make use of British, French and Italian liners and eighteen interned German liners, the most famous of which was the Hamburg-Amerika Line's Vaterland, renamed Leviathan. That ship on one record voyage carried 10,860 troops. American convoys, including troop convoys from New York were sent directly to the Bay of Biscay and French ports, and joined the existing British convoy system. The older warships of the Navy, notably cruisers or even gunboats dating from the Spanish-American War, may not have been of much use in a formal naval battle, but were useful enough for ocean convoy escorts. On the other side of the Atlantic an escort of four destroyers usually met a convoy at the 15th meridian. In January 1918, the Naval Overseas Transportation Service was established to run these movements, controlling as many as 375 ships at a time.

K class submarine

In the course of the war, both sides laid extensive mine fields in the North Sea. The largest and most ambitious was generally known as the “Northern Barrage.” The Americans were the primary movers behind the project, which involved a series of minefields across the North Sea, extending from the Orkneys to the Norwegian coast. The US Navy was responsible for laying Area A (130 miles), the longest of the three areas, while the British were responsible for the westernmost Area B (fifty miles) and the easternmost Area C (seventy miles). The idea was to close or hamper the exit of submarines north of the British Isles. The Americans employed a newly developed “antenna” mine, as opposed to the widely used “contact” mines. A special loading dock was prepared near the Norfolk Virginia Navy Yard for the fleet of over twenty “Lake” class cargo ships that transported the mines across the ocean. The American mine force was commanded by Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss. The formation charged with laying the mines, Mine Squadron One of the Atlantic Fleet, consisted of the old cruisers San Francisco and Baltimore and eight coastal steamers or merchant ships converted for mine laying. The American mine laying capabilities were greater than those of the British, with some ships laying over 5,500 mines in a four-hour period.

Consequently, they eventually joined the British in laying areas B and C. The Americans lay over 56,000 of the 70,000 mines eventually installed. The technical preparations for the project took considerable time. The British did not begin their mine laying until 3 March 1918, while the Americans did not begin until 8 June. The Americans had similar plans for the Adriatic and Mediterranean after the Northern barrage was completed, but the war ended before they could be implemented. The project was controversial. Certainly a few submarines - estimates are six - might have been sunk, but whether these results were commensurate with the immense effort and resources expended is debatable. Moreover, by the time the barrage was laid the convoy system had already been effective in decreasing the losses to submarines.

The US Navy in the First World War did not participate in any major action, and its role has been overshadowed by the hard fighting associated with the much larger military forces on land. Nevertheless, the Navy contributed significantly at a critical moment in muting the German submarine threat, and played an equally important role in assuring the logistical demands of the American Expeditionary Forces in France. By the end of the war, the United States had committed considerable naval and maritime forces to Europe. The time needed for those substantial forces sometimes seemed too slow to the hard pressed Allies. Nevertheless, the scale of the American effort became apparent in the final six months of the war. Much of this effort, such as the large building programs, was of potential importance and would likely have played a considerable role had the war lasted into 1919. The potential of American industrial strength was clear and foreshadowed the American naval program during the Second Word War.

*In 1920, Queenstown reverted to its original name of Cobh (pronounced “cove”) which is near Cork, and Kingstown reverted to being Dun Laoghaire, near Dublin, and where US destroyers were also based in the later stages of WWI.

- Details

- Category: Articles

Terry Jackson

In 1914 the German Army went to war with the traditional spiked helmet made of leather. As with the other belligerents, the rapid increase in artillery firepower meant that something more resistant to shrapnel and flying debris was needed.

The first attempt to give some protection was by the Army Group Gaede* in early 1915. (*The unit’s commander). They were active in the Vosges. It is a very rocky area and many of the trenches were in rock cuttings. This led to a high level of splintering from shell explosions with the inevitable effect of wounding, especially to the head.

With no immediate developments at the national level, the group decided to design one themselves. Lt-Colonel Hesse the Chief of Staff headed the project. This was a specialised skull cap somewhat more developed than the French calotte and included a nose-guard. It was quite heavy and a small cloth and leather cap was worn underneath for comfort. The steel was 5-7mm thick and weighed 2.05kg. Most were subsequently melted down and are rare nowadays. (Photo right: Gaede helmet: see end of article for other helmets).

At a more national level, in 1915 Professor Friedrich Schwerd of Hannover Technical Institute and also a Captain in the Landwehr, was in contact with Professor August Bier, the Naval Doctor-General and an army consultant. Schwerd had set up an electromagnet with which he intended to extract splinters from the brains of injured soldiers. During their conversation Schwerd assured Bier that a helmet could be produced to protect against splinters and shrapnel, but not bullets, A study of 100 head wounds showed only 20% were from bullets, the remainder being from shell fragments or shrapnel. A very small splinter could cause massive brain damage and most head wounds were sufficiently severe to take the soldier out of army service. Bier sent this information to 2nd Army. Both experts were of the opinion that a protective helmet could and should be developed. (Photo right: Professor Schwerd)

Copies were sent to the various Army doctors and von Falkenhayn then Chief of General Staff. He in turn advised the Prussian War Ministry that this should be acted upon. After high level discussions in August the War Ministry informed informed Krupp Essen that the Juncker Foundry in Berlin would develop the helmet and Krupp were to provide the steel.(Junker had already been experimenting with steel helmet designs). By September 1915 after taking expert advice Schwerd reported to the Clothing Section of the War Ministry that a helmet should be produced.

The helmet was to be of 0.5mm thick steel with neck and forehead protection. 5% nickel steel was preferred, but 11% manganese steel could be used. It would be able to protect against shrapnel and small splinters but not bullets. Two side vent lugs would allow ventilation. Anti-rusting paint and a top coat would be applied. Consideration was then given to design based on the statistics-. 80% of head wounds were from artillery fragments/shrapnel and only 20% from rifle fire.

By September 1915 Schwerd had determined what rationale was required for the production of a helmet and had discussed the matter with several specialist companies. It would be designed to give protection against shrapnel and splinters. Protection against rifle bullet penetration was not feasible as the weight of the extra protection would make the helmet too heavy to be worn. Splinter fragments would threaten from any angle. The helmet also had to allow for soldiers firing whilst lying down. Thus the characteristic shape of a bowl with a peak, a dip by the ears and neck protection produced its recognisable shape, which was similar to knight’s helmets of the past. The helmet would have two proud lug holes to the sides for ventilation and a liner with three pads and a chin strap attached to the internal part of the lugs. After much discussion a separate metal forehead shield was developed which could be strapped from the side lugs. In theory this would assist snipers as they would be firing from a fixed spot and muzzle flash might reveal their position. It proved to be unpopular and was not extensively used.

Various factories were employed in the trials and manufacture of the helmet and liner, reflecting Germany’s abundance of specialist engineering and military equipment companies.

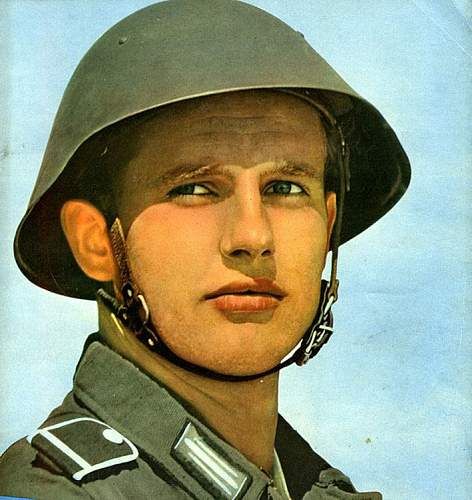

Eventually after many reviews, it was aimed to produce a one piece helmet of 5% nickel steel or 11% manganese steel. After considerable testing, the first shipment of helmets for field study was sent to Captain Rohr’s 1st Assault Battalion in December 1915. These proved satisfactory and by February 1916 they were being used at Verdun. Following good field results, von Falkenhayn authorised a general issue in the same month. The Allies soon became aware of this development and the Parisian newspaper ‘Le Temps’ carried an article on the helmet on 10 March 1916. Gradually more units were issued with the helmet. Austria purchased 416,000 in late 1916 and began producing its own model in May 1917 and manufactured 534,000 themselves. Minor adjustments such as the toning down of light reflection and liner improvements were made over time. (Photo right: Willy Rohr).

In September 1916, through its Military Attaché in Washington DC the Americans attempted to purchase a specimen, but the Prussian War Ministry were unable to oblige. However, one was eventually given to the Americans via Paris.

Turkey also ordered helmets from Germany in 1918. The front visor was removed and the sides trimmed. It was suggested that was to enable the soldier to touch his head on the ground during prayer, but it was to give better ventilation. Only 5400 were delivered. (Photo right: helmet with visor)

In 1918 a variation was introduced with cut outs at the side. This has often been identified for use by wireless operators to accommodate headsets. However, it was to give better ventilation and only limited numbers were issued. As Germany struggled towards the end of the war, recycling of used or damaged helmets was common due to the shortage of material caused by the Allied blockade. It has been estimated that about a million helmets were produced during the First World War

After the War various organisations wore the helmet during the internal struggles in Germany. Prior to the Second World War the helmet was redesigned. It retained the traditional shape but with a shallower bowl of thicker metal. The external lugs were removed, the side air vent being flush. Various internal organisations (Fire/Police etc) had adapted designs. German paratroopers were issued with a brimless helmet.

Towards the end of the Second World War a new design was being tested. Although similar to the original it had no turned curves which were a structural stress weakness. It was the helmet adopted by the East German Authorities until re-unification. Like most other nations Germany is now using a composite material helmet.

(For further information see ‘The History of the German Steel Helmet 1916-1945 by Ludwig Baer-ISBN 0-912138-31-9. Several other books are available that cover helmets and body protection).

Cut-out helmet

Cut-out helmet

Body armour

Current German Helmet

East German Helmet

Sniper shield

Square-dip Helmet

Visorless Helmet

- Details

- Category: Articles

Terry Jackson

When war broke out, Norway had been an independent country for only nine years. With fewer than 2.5 million inhabitants in 1914, more than half of Norway’s population depended on farming or fishing for their livelihoods. Industrialization was still ongoing. The Liberal Party had been in government since the election in 1913. Universal male suffrage had been established in 1898, and universal female suffrage in 1913. Of the Scandinavian countries, only Finland was ahead of Norway in this respect,

Peaceful dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905 had an obvious consequence: Norway had to establish a foreign service, as the foreign policy of the united kingdoms of Norway and Sweden had been run from Stockholm. Norwegian diplomats and bureaucrats stepped down from the “old” service and joined the “new”. However, it was still necessary to establish a Norwegian foreign policy and to decide what role the Foreign Service and the diplomats were to play. The Foreign Minister Jorgen Løvland outlined the two main directions to be pursued in the country’s foreign policy in a major talk to the Norwegian parliament on 26 October 1905: ‘Neutrality in combination with an active trade policy’.

Løvland outlined a foreign policy rooted in a perception of Norway’s geographical remoteness from the areas of conflict on the European continent, and a wish to be left alone in order to get on with building a new nation. The policy focused on active international trade relations. Neutrality became the cornerstone of this policy, with an emphasis on no political alliances that might drag the country into other peoples’ wars. However, at heart the Norwegians believed that Britain would protect the country and its economic assets in the case of a European war between the great powers. Thus, in 1914, Norwegian foreign policy was understood to be essentially trade policy, and the Norwegians were well aware that they were within the British sphere of influence.

The Norwegian foreign trade policy was based upon a belief in international law. As an early promoter of arbitration, Norway had been at the forefront of promoting international cooperation and arbitration as a means to settle conflicts peacefully. The First World War represented a huge blow to this belief. Still, Norway believed that the rights and duties of neutral countries, as they were drawn up in The Hague Peace Conference in 1907 and in the London Declaration of 1909, would be respected. It took only a couple of months of war to prove them wrong.

The summer of 1914 was very hot. In Kristiania (Oslo). There had been a great exhibition celebrating the centenary of the Norwegian constitution. Everything seemed normal. The crisis in late July 1914 took the Scandinavian countries by surprise. On that fateful day in July, Prime Minister Gunnar Knudsen was out sailing when news of the Austrian ultimatum to Serbia broke. As a result, the Norwegian Prime Minister cut his holiday short.

When Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August, Norway, along with Sweden and Denmark, issued a declaration of neutrality. On 4 August the Norwegian government issued an additional, separate statement again emphasizing its neutrality. Two days earlier, the Norwegian navy had been mobilized and soldiers were sent to man the coastal fortresses; the neutrality guard was thus established. Norway was ready to defend its neutrality, despite being both politically and militarily unprepared for war. The armed forces had not fired a shot since 1814, and the political authorities had no experience of international crises.

The first priority of the government was to keep Norway out of the war; the second was to provide supplies in order to feed the population and maintain economic stability. The catastrophic effect of the British blockade during the Napoleonic Wars was still a part of the collective memory. Keeping the country out of war and providing the country with necessary supplies was a fine balancing act between two interwoven objectives. Thus, the policies of neutrality and the nation’s economic policies were inseparable.

The awareness that war was coming created a short-lived panic. There was a huge increase in the demand for certain foodstuffs; prices rose dramatically for flour during the last days of July. By 1 August, several of the large importers in Christiania were sold out. In response, the Bank of Norway raised the rate on discount from 5% to 6%. On 3 August the panic hit the banking sector. Due to the limits imposed two days earlier, the Bank of Norway was able to meet the demands for currency and could continue to pay out gold. That same day the interest rate was raised again, this time to 6.5 percent.

In August 1914 the first Norwegian declarations concerning export prohibitions and price regulations had been published. Further declarations were to follow. These declarations made it possible for the state to control much of the economy. The government issued an export ban making it impossible to sell Norwegian ships to other countries. The government was able to regulate the merchant navy and keep it sailing.

Due to the economic precautions taken during the autumn of 1914, the government shifted towards new policies, intervening in the market in a way previously unknown. The primary goal was to secure the necessary chain of supplies. Neutrality soon became essential. Most other countries adopted similar policies, but in Norway, the merchant fleet’s crucial role was unique. Heavily dependent on the income generated by the merchant fleet and needing to import supplies, the war at sea had a large impact on Norwegian daily life. When Britain issued the first Order in Council on 29 October, the grip on the neutrals tightened. The North Sea Declaration on 2 November completed this step. Through militarizing the North Sea, the neutrals were forced to follow British instructions and thus come under British control. Those who did not follow British instructions ran the risk of sailing into minefields.

The British policy of commerce towards Norway was established as early as 15 October 1914. On that day the Norwegian Foreign Ministry received a letter from the British stating that the Norwegians had to stop the re-export of goods that, according to the British definition, were contraband. The intent was to make the blockade of Germany more effective. The Norwegian government was put in a difficult position. On the one hand, the Norwegian government had already established its own export prohibitions. These were based solely on domestic needs. To include a set of new prohibitions based on British demands put Norway’s neutrality at stake. On the other hand, the Norwegians could not afford to ignore the British demands as Norway was heavily dependent on Britain to keep the economy stable.

At first the British measures towards neutral shipping and trade were tolerable, although they conflicted with international law. When Norwegian ocean liners were given safe sailing routes north of Scotland, allowing them to bypass British harbours, the British granted an exemption from the Orders in Council. However, the basic problem still remained: British interference and attempts to regulate neutral shipping provoked German reactions.

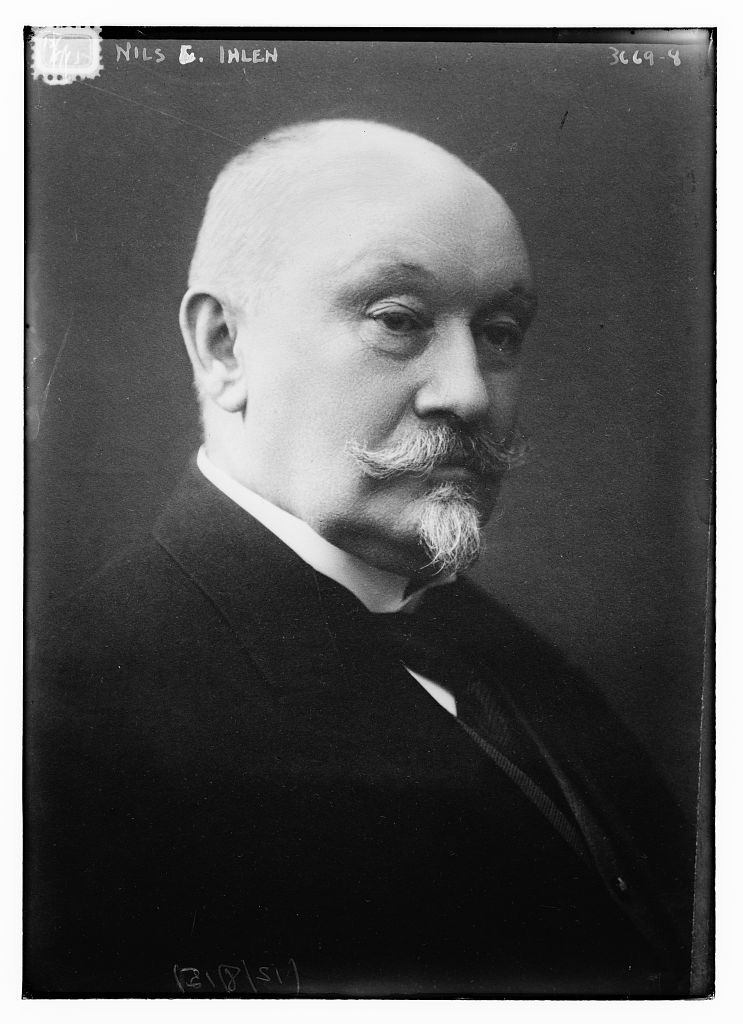

When the Scandinavian governments met in Gothenburg in the middle of December 1914, the problems caused by the belligerents were at the top of the agenda. Shortly after this meeting, the Norwegian foreign minister, Nils Claus Ihlen met the German minister to Norway, Alfred von Oberndorff. Ihlen dismissed the idea that Britain was a threat to Norwegian neutrality, but he expressed concerns about the consequences of British pressure on Norway. Given its dependency on Britain, Ihlen indicated that Norway could be forced to stop exporting certain Norwegian products to Germany.

When war broke out, the Norwegian government, like most European governments, believed that it would be short. As the war dragged on the lack of planning for a longer war became problematic. (Photo right: Nils Claus Ihlen)

From an economic point of view, the history of Norway during the First World War can be divided in two periods: before and after autumn 1916. Through the autumn of 1916 business had remained relatively normal, given that most of Europe was at war. Ihlen had been able to deal with Norway’s difficulties, but his somewhat ad hoc policy was based on his belief that the war would be short. A successful businessman fluent in French and German, he firmly believed that peace was near and that his main object, therefore, was to avoid acute conflicts. It would be foolish to push any difficult situation to the extreme if the war came to an end at any moment. This was a pragmatic approach, but as the war continued, the room to manoeuvre decreased, making his ad hoc approach untenable.

Economically, Norway’s position as a neutral country was favourable, but politically it was vulnerable. Unable to feed itself and heavily dependent upon overseas imports which were completely under British control, Norway was in an exposed position. IIhlen told the Storting (Parliament) that Norway was the weakest of the three countries because it was not under threat of German invasion or likely to join the Central Powers, and was hence wholly exposed to British pressure. While Germany was interested in keeping Norway neutral and thus continuing to receive supplies from it, Britain wanted Norway to become a part of the economic blockade of Germany and thus deny Germany the supplies it needed. The “weapons” used against what the British wartime naval attaché in Scandinavia called “our best friend, and from whom there were no political consequences to be feared,” gave Norway the “worst treatment of the three Scandinavian States at the hands of the British Government”. Norwegian neutrality was thus at risk from the outset.

Believing that it would be possible to continue to trade with the belligerents according to the Declaration of London of 1909, Norway and the other neutrals faced a number of challenges as early as 20 August 1914. On that day the British government issued an Order in Council stating that conditional contraband would be subject to capture if the goods were consigned to an agent of any enemy state, or to any person in territory belonging to or occupied by the enemy. It also made conditional contraband en route to enemy countries subject to capture, even when it was to be discharged in an intervening neutral port. Conditional contraband was liable to capture to whatever port the vessel was bound and at whatever port the cargo was to be discharged. In practice, therefore, all transport of goods to the Central Powers that had to pass the British Navy came to an end.

Norway had fewer problems with this than other neutral powers did. The Norwegian fleet was able to sail from Norwegian through Swedish territorial water into the Baltic Sea, where the German Navy was in command. But it soon became more difficult. A new Order in Council, issued on 29 October, increased British pressure on the neutrals; most of the raw materials Germany needed were transferred from the conditional to the absolute contraband list. A few days later, on 2 November, the British Admiralty declared the whole of the North Sea a military area. Coming into effect on 5 November, all ships passing a line drawn from the northern point of the Hebrides through the Faroe Island to Iceland did so at their own peril. Ships wishing to trade to and from Norway, the Baltic, Denmark, and Holland, were advised to come, if inward bound, by the English Channel and the Straits of Dover, where they would receive sailing directions which would pass them safely, as far as Great Britain was concerned, up the coast of England to Farne Island.

The Norwegian government protested, but even though negotiations resulted in some adjustments – such as the course north of Scotland given to Norwegian liners – the end result was an ever-increasing British control over Norwegian shipping and foreign commerce.

Through the economic policy initiated by the Norwegian government in early August 1914, the government intervened in economic life in a new and more active way. The most pressing problem was to secure the necessary supplies of food and fuel. A provisional statute from 4 August imposed a prohibition on the export of necessities. Price control was imposed and a “food commission” was established which had the power to requisite supplies. Large-scale imports of grain were undertaken. However, the Norwegian government was reluctant to set up a central import agency controlled by the government, as Britain wanted to reduce friction with the neutral states and to achieve more systematic control over German trade. The government shied away from any direct involvement which might make it a party to anti-German and hence non neutral trade restrictions. Instead, the government left the issue of handling the different arrangements with the British to shipping companies and import/export firms.

If the war had been short, this ad hoc response might have been a viable solution. Unfortunately for Norway, as Germany turned to submarine warfare after Britain tightened the blockade, the impact on the Norwegian economy made this solution inadequate. It soon became necessary to reach an understanding with the British government that would ensure Norway’s ability to receive supplies.

The British blockade was based on denial – denial of resources that the other party needed. As Britain tightened its blockade, the Germans grew increasingly worried about their access to fish, copper, pyrites, and similar items from Norway. Since Germany, unlike Britain, was unable to exert direct pressure, they were left with diplomatic protests – and their submarines.

In the long run it was too burdensome for Britain, especially for their representatives in Norway, to keep track of the firms that had signed guarantee agreements. Thus, a system of “branch agreements” developed, whereby the different branch associations of Norwegian producers or importers acted as middlemen between the British authorities and the individual Norwegian firms. These arrangements covered most of the Anglo-Norwegian trade and were later supplemented by direct government export bans.

In the spring and summer of 1915 Germany started to purchase large quantities of fish, essentially buying everything they could get hold of, thereby driving up the prices. For the Norwegians, the result was two-fold. First, fish became so expensive that fish products suddenly became a luxury. Secondly, because of the German demand for fish, it became difficult for Norwegians to get hold of fish at all. The Fishermen no longer brought their catch to land, but sold it to German boats whilst still at sea. The British wanted this trade with the Germans to stop. Since they controlled the necessary supplies for the Norwegian fisheries – coal and oil – they were able to influence the Norwegians.

However, fish and fish products were of vital importance for the Norwegian economy, constituting approximately one-quarter of Norway’s export earnings. Sensing that its fish industry was threatened, Norway managed to persuade Britain to agree to buy Norwegian fish through secret agents and thus create a “buying blockade”. The purchases started in February 1916 and went on for about two months. However, this plan had its own difficulties, as the presence of a buyer with seemingly unlimited financial resources had an explosive effect on prices. It soon became clear that this could not continue. Having spent £11 million on fish they neither needed nor wanted (The only purpose being to keep the fish from reaching Germany),the economic cost was too high for the British. In August 1916 the “Fish Agreement” between Norway and Britain was signed. As had been true with the branch agreements, Norway received the supplies it needed, and – despite the prohibition on exporting fish, fish oil and other fish products – the right by treaty to export 15 percent of its fish to Germany. Britain was obliged to buy all fish that was not required for home consumption in Norway at fixed prices.

The conflict over Norway’s export of fish coincided with the conflict over the Norwegian export of pyrites to Germany. Norway both exported and imported copper; it exported cupreous pyrites and imported electrolytic copper. After Britain gained control of American copper exports around Christmas 1915, the pressure on Norway increased. In April 1916 Foreign Minister Ihlen received a lengthy note from Mansfeldt Findlay, the British envoy to Norway. The letter was written in an unusual diplomatic tone:

I wish to point out that, as far as my Government is aware, no other neutral State is exporting to the enemies of Great Britain material for the manufacture of munitions of war, and is at the same time expecting Great Britain to facilitate the importation of the same material. It is practically certain that the copper exported from Norway is used for the manufacture of the shells which day after day are causing the death and disablement of the soldiers of Great Britain and her Allies. It is even probable that copper dug in Norwegian mines is part of the material used in the construction of submarines by which so many Norwegian ships have been destroyed 'with due considerations for the rights of neutrals', and not a few Norwegian sailors killed or wounded. The inflated price of Norwegian copper is, in fact, the price of blood, – the blood of the friendly people to whom Norway would necessarily look for assistance in time of need, and on whom she depends, not only for the continuance of her present prosperity and independence, but for her existence as one of the foremost sea-faring nations of the world.

Ihlen replied a few days later, claiming the right of neutral states to trade with both sides in wartime. Nevertheless, the summer meetings between Britain and Norway, which resulted in the “Copper Agreement” on 30 August 1916, cut off Norway’s export of copper pyrites to Germany. Its terms became the subject of misapprehension which proved nearly catastrophic for Norway’s relations with both belligerents.

The agreements on fish and pyrites represented a turning point in Norway’s relations with the belligerents. Through these agreements Britain gained control over two of Norway’s main domestic products in direct cooperation with the Norwegian government. But it can also be argued that this was just one of many small steps during the war. Norway moved in the same direction throughout the war, always towards Britain.

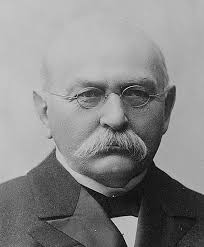

One of the first measures taken by the Norwegian government in August 1914 was to appoint a committee of experts to decide how to keep the Norwegian merchant navy sailing as the risks increased from floating mines and submarines. The war offered many opportunities to transport goods, but the old insurance policies did not cover war risks, and it proved impossible to buy proper insurance with reasonable premiums. (Photo above right; Fridtjof Nansen in later years)

The Norwegian merchant navy was quite large; in relation to its population it was the largest in the world, with 1,031 tons per inhabitant (and the fourth largest in absolute terms with 2,559,000 gross tons). Moreover, the Norwegian ship owners were known for their inclination to charter their ships for dangerous voyages when high profits were tempting. With a large fleet and ship owners eager to take on the risk, the Norwegian government could not let the Ministry of Finance take over a substantial share of the risk, as had occurred in Denmark and Sweden. The solution presented by the expert committee was a mutual but compulsory insurance. A new institution – Krigsforsikringen for Norske Skib (the Bureau of War Insurance) – was established to cover the ships; a limited company – Varekrig ("War of Commerce") – was later formed to take over the insurance on commodities against war risks. The risk was split between Varekrig (20 percent) and the Norwegian state (40 percent), while private interests reinsured the rest.

Thus the Norwegian merchant navy was able to keep on sailing. Indeed, for the first eighteen months of the war the amount of cargo continued to increase. One of the “specialties” was to carry coal from Great Britain to France. At the outbreak of the war much of the Norwegian merchant navy was engaged in tramp traffic. While this brought in a lot of money as the amount of cargo increased, the risk was also large. Norway lost 889 ships during the war (1,296,226 tons), almost half of them, 423 in 1917 alone. Additionally, some 2,000 sailors were drowned.

However, in May 1916 the British and French authorities announced that they had reached an agreement imposing maximum rates on the coal trade. Furthermore, the neutrals had to accept these terms if they wanted to bunker coal. After threatening to stop sailing, the Norwegian ship owners negotiated somewhat better conditions. This was in many ways the turning point, the period when the prosperous era for Norwegian shipping ended. The pressure began to increase; dependent upon the British and subject to German submarines, the Norwegian merchant navy faced a stormy sea.

In the autumn of 1916 German submarines made their way to the Arctic Sea. They caused an uproar in Norway when at the end of September they started to sink ships engaged in traffic with Russia through Archangelsk. The Norwegian newspapers ran headlines such as, “De døde kalder” (“The dead are calling”). Publishing details from the Marine Enquiries, the press pressured the Norwegian government to act. On 13 October the government issued a Royal Decree, stating that “Submarines, equipped for warfare and belonging to a belligerent Power, must not navigate or stay in Norwegian maritime territory. If they violate this prohibition, they risk being attacked by armed forces without warning”. The only exceptions were for bad weather or shipwreck to help save sailors, but even then the submarine was to stay on the surface flying its national flag and have a signal showing the cause of its presence.

It was no surprise that the reactions in Germany were harsh, of which the Norwegians were scared. Internationally this was also perceived as a crisis. Germany used this perception as leverage to push for better conditions in trade negotiations that had been opened before the Submarine Decree was issued. Germany also wanted the decree to be withdrawn, as it was pushing for the use of submarines to be recognized as a legitimate means of economic warfare – that is, as a tactic equivalent to the British blockade.

For Norwegian shipping, the autumn of 1916 was a disaster. Krigsforsikringen insurance took heavy losses as merchant ships were sunk, and in October the Bureau refused to insure voyages to the Arctic Sea. At the same time, there were rumours that the insurance premiums were going to increase and that the Anglo-French coal trade was in jeopardy. That worried the British government, which thought that Norway might give in to German demands. The crisis with Germany calmed down as negotiations proceeded in November and December 1916. Formally, however, it was not settled until the end of January 1917 when a trade agreement was signed and changes to wording of the Submarine Decree were made.

For Norway, the situation went from bad to worse as Britain imposed a ban on the export of coal to Norway at the beginning of January 1917. The British claimed that Norway had not fulfilled its obligations towards Britain based on the agreements on fish and pyrite exports to Germany. Four days after Norway failed to reply to the British memorandum of 18 December, the British government ordered an embargo on coal exports to Norway. For Norway this was a catastrophe; the winter of 1916/17 was quite cold. Thus, it was not only a question of economic survival but would also severely strain the civilian population if it continued.

The Anglo-Norwegian conflict did not end before mid-February 1917, when Norway informed the British government that they were willing to cease all pyrite exports to Germany. The German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare made this choice easier, while the German arguments for doing so seemed less valid. But the Norwegian Prime Minister still questioned the British motive behind the coal embargo. Nevertheless, the Norwegian Merchant Fleet had been brought into play.

Britain had long been afraid that all neutral shipping could be brought to a standstill. In February, Britain made gestures towards several neutral countries regarding a possible purchase of neutral ships by the British government. The British initiative was discussed and rejected, but the problem remained unsolved: Was it possible to reduce the merchant navy’s huge losses?

The alternative to buying (and thereby arming) a merchant fleet was simply to charter and switch the unarmed Norwegian ships with armed allied ships on the most exposed routes where losses occurred. The Norwegian government suggested this. Towards the end of April 1917 the Norwegian parliament accepted the transfer of ships by chartering or requisitioning. The deal between Norway and Britain was signed by representatives from the Norwegian Ship Owners Association (Rederforbundet) shortly thereafter, and thus camouflaged the Norwegian Government’s role which indicated::

As a return for and conditional on the concessions embodied in the agreement as regards the supply and transport of coal to Norway, the Rederforbundet has declared itself willing to enter into this understanding, with a view to increase the Norwegian tonnage employed in allied trade, while at the same time safeguarding as far as humanly possible Norwegian seamen’s lives and Norwegian shipping property by the substitution of British ships for Norwegian in the Anglo-Norwegian trade.

Norway had become the neutral ally. As it turned out, it was the (re-)introduction of convoys that reduced the losses from the peak in March 1917, when sixty-six ships – more than 100,000 tons – had been sunk or damaged. From the end of April 1917, all trade between Britain and the Scandinavian ports sailed in organized convoys escorted by the Royal Navy. By July the losses had been reduced by more than 50 percent.

Keeping Norway out of the war and simultaneously providing the supplies needed to feed the population and keep the economy running was a complicated task. Norway did not wish to be dragged into the war, but at the end of the day it was up to the belligerent parties. The crucial question was if any of the belligerents wanted to involve Norway in the war. In that sense, Norway and the other Scandinavian countries were more fortunate than most other European countries. Both the Entente and the Central Powers were persuaded that they had more to gain from Scandinavian neutrality than from drawing the Scandinavian states into the war. Scandinavia proved marginal to the military and naval strategies of the belligerents to an extent unforeseen by pre-war planners.

But although the conflict between Norway and Germany from the Norwegian submarine decree in October 1916 had calmed down, Germany wondered how it would cope if Norway joined the Entente. In 1916 Germany had no answer to this question. In December 1916 the German Admiral Staff started to think through how Germany would respond.

During the first few months of 1917, the German Naval Staff completed “Kriegsfall Norwegen,” a plan for war with Norway. The plan was based on a situation in which Norway had joined the Entente – whereby Britain gained access to the Norwegian coast. “Kriegsfall Norwegen” concerned Norwegian territory only indirectly, with the possible exception of the bombing by Zeppelins of towns and factories in southern Norway. The operational orders included the laying of minefields and occasional advances of the High Seas Fleet. The German army was not to participate in this plan. Because of the German naval strategy during World War I, the naval staff did not regard the opening to the Atlantic in the same light as it did in 1940. All it saw in 1917 was the entrance to the North Sea. Because the south coast of Norway is geographically closer to Germany than Britain, British naval bases here could be used not only to control the North Sea, but also as a base for an invasion of Denmark. Danish territory could then be used as a base from which an attack on Schleswig-Holstein could be launched. The Norwegian coast was also important for controlling the exits from the Baltic. The combination of the German naval strategy and the British influence on Norwegian foreign policy created a situation in which the Norwegian position was never as threatened as when Norway requested or was offered British support – the picture of safety in the politicians’ minds. That was the only scenario that could trigger “Kriegsfall Norwegen.” (Photo above right: Gunnar Knudsen).

The Tonnage Agreement could have triggered harsh German reactions if it had become known, but even that would probably not have led to a situation for which “Kriegsfall Norwegen” would have been activated. As negotiations between Great Britain and Norway were taking place in the spring of 1917, rumours were flying in Berlin about a British interest in establishing bases in Norway. Erich Ludendorff expressed concern, but the situation calmed down after about a month. In Christiania, the Norwegian Foreign Minister claimed that “there is not a single word of truth in these rumours” (“an den Gerüchten kein Wahres Wort sei”).

One could argue that the Tonnage Agreement established Norway as the “Neutral Ally”. However, Norway had been drifting towards Britain from the beginning of the war, a process that continued as the war lasted for another year. Even though US President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) had viewed Norway as a special case – he drew a distinction between Norway and other neutral countries – the negotiation of a trade agreement between the USA and Norway became difficult. The Norwegian delegation, led by Fridtjof Nansen arrived in Washington in July 1917, but an agreement was not signed before the end of April 1918. In the autumn of 1918, Norway gave in to Anglo-American pressure and completed the Northern Barrage, closing “the gap” by laying mines in Norwegian territorial waters.

As was true in neutral Denmark, the war created favourable conditions for Norwegian business. After the short panic in August and a period of uncertainty in the autumn of 1914, unemployment decreased in 1915 and was remained quite low for the rest of the war. But government intervention in the market, including the establishment of maximum prices for certain vital commodities and the prohibition against using grain or potatoes to produce alcohol (a temporary prohibition on the selling and retailing of liquor was introduced in 1914 and made into law in 1918), could not prevent shortages of certain foodstuffs and fuel. Black markets flourished and basic foodstuffs became both expensive and scarce. Nevertheless, rationing was not introduced until January 1918, and then only due to demands by the USA.

Government regulation could not stop the war from creating an economic boom that led to changes within Norwegian society as wealth became more unevenly distributed. Thus, while a few became very rich (the stock market boomed and shipping trade went through the roof) and farmers and fishermen earned good wages due to the blockade, the lower level civil servants and the labour class suffered as their wages struggled to keep pace with the increasing prices. From the outbreak of war in August 1914 until the summer of 1918, the cost of living rose by about 250 % (and a new boom in 1919 and 1920 worsened the situation) Society was divided between those who were able to pay for goods, whatever the price, and those who could not.

As a consequence of this divide, the year 1917 saw the greatest demonstrations in Norwegian history. Over 300,000 people took to the streets in June to demonstrate against a lack of food and money to pay for necessities (dyrtid). In Christiania (Oslo), more than 40,000 demonstrators participated. The Labour Party – which had its breakthrough in the parliamentary elections in 1912 – was radicalized during the war. From 1918 on, the Labour Party considered revolution to be a possible answer to the challenges the country faced.

What is the legacy of the First World War within Norwegian society? The answer to that question remains unclear, In comparison to its Scandinavian neighbours, it is striking how few long lasting effects the war had on Norwegian culture. Print media and public opinion were pro-British; few voices supported Germany.

Norway’s history during the First World War is a history of change, both externally and internally. Within the history of foreign policy, it is the history of how Norwegian politics and neutrality adapted to the war; how Norway became an important contributor to the allied blockade of Germany, given that Norway’s aim was to preserve its neutrality. This occurred out of necessity – there was simply no other way to secure the economic welfare of the country. But as the German submarines continued their missions, it became much easier for the Norwegian government to follow a policy that favoured the Entente. From 1917 onwards the nation’s sympathies were firmly aligned with its policies.

The war forced the Norwegian government to take measures to secure production and commerce. The government intervened and regulated the economy more than ever before in order to secure the import of food and other essential commodities. This intervention could not prevent Norwegian society from being split between those who were able to adapt to the situation because they had the means available, and those who suffered from the hardship created by the increased cost of living. Growing support for – and a radicalization of – the Labour Party followed. One consequence of this radicalization was that the electorate system was reformed in 1919 to meet the claims on representation from the working class. The old system of single constituencies had strongly favoured the governing parties, while the new electoral system, based on the principles of direct election and proportional representation in multi-member electoral divisions, paved the way for the first Labour government in 1928.

The war drained the Norwegian government financially. Financing the neutrality guard was costly, as thousands of men were mobilized for more than four years. However, the real cost of government regulations (the purchase of supplies, etc.), was hidden in the irrational bookkeeping of the Ministry of Finance. Deprived of knowledge of the latent losses, the National Assembly believed that the finances were in a flourishing state. It was not until two years after the war that the real situation – that Norway had accumulated a massive debt during the war – became known. In the 1920s, shifting Norwegian governments were left with a troublesome economic situation. This became even more difficult because of the decision to re-establish the gold standard of 1914.

In addition to the economic consequences, the main legacy of the First World War was that it confirmed Norway’s perception of its security. It was possible to stay neutral in a war between the great powers. Situated at the European periphery, with both Germany and Russia (the Soviet Union) reduced from their former glory there was no threat to Norway’s independence. This became the foundation for Norwegian defence policy in the interwar period, a perception that was to be proven wrong in 1940.