Switzerland gained independence from the Holy Roman Empire in 1499. Swiss mercenaries had a fearsome reputation, but aware of its small it size became neutral. It was occupied by Napoleon in 1798 but, after his demise, it was guaranteed neutrality by an international treaty. By 1841, it had a federal constitution with 23 Cantons.

In August 1914, fearful of being used as a short cut by either France or Germany, the army was mobilised to avoid the fate of Luxembourg and Belgium. Like other neutral states, the next phase was the forming of trade links with the belligerents. However, by 1916 the war had caused a universal negative effect of inflation, civil unrest and shortages of food and raw materials.

Under the 1907 Hague Agreement, neutral countries could export goods, including arms, to belligerents. Sick soldiers could be transported through a neutral country, but not troops. Switzerland could sign alliances, but had to treat all states equally.

Some 73% of the Swiss population were German speakers, often with continuing links to Germany. Many studied in Germany and some army officers received training there. The French speakers (23%) had similar links to France. Initially, the general sympathy was towards Germany but this changed after the invasion of fellow neutrals Belgium and Luxemburg.

After an initial fear of invasion subsided, the Swiss became concerned over the interruption to food supplies. Trade was based on importing raw materials and exporting goods, but, like Serbia, it had no direct access to the sea which it needed to import and export to survive. The Allies and the Central powers with self-interest allowed trade to continue.

When Italy eventually joined the Allies, Switzerland was effectively landlocked. However, although Germany controlled the Rhine, it did not attack ships that were bringing material to Switzerland as they, too, needed high Swiss quality goods based on imported raw materials. Ports such as Sète (in southtern France) were not threatened by U-boats and remained open. However, the Allies would not export any goods to Switzerland that could be passed to Germany.

In terms of actual trade, the Allies needed as many shells as possible and the Swiss potential was significant. The British Ministry of Munitions opened an office in Berne in September 1915. Concurrently, the British Government and a Swiss company signed a contract for the manufacture and supply of 100,000 type-100 fuses per week for six months. This was the first of many orders. In September 1916 the Swiss agreed to make 5.2 million of the new 106 ‘graze’ fuse, vital for cutting wire.

By the Armistice, the Swiss had made 25 million fuses for Britain and 121 million fuse components, all made by highly skilled labour. Other items included 32,750 aeronautical watches, 19,000 aircraft barometers, 75,000 precision compasses and even parts for Rolls Royce engines. When Italy entered the war, it, too, purchased munitions from the Swiss. (Photo right - PoWs arriving)

As Swiss raw materials were limited, it had to purchase and import them from abroad. Steel was imported from Britain and the USA provided brass for the 106 fuse. Germany created a black list of factories making Allied munitions and ensured no coal, steel or iron was sent from Germany to Switzerland.

Germany did obtain munitions from the Swiss, but the financial value of the allied material produced was 32 times greater. After the 1915 shell scandal, the Entente was generally on the offensive (save for the 1918 Spring Offensive) and huge quantities of ordnance were needed. During 3rd Ypres, Britain fired 32 million shells from 3,500 guns and a significant amount was Swiss manufactured. The 106 fuse not only could cut wire, but it produced smaller craters allowing the advancing infantry better movement.

In review, British Inspectors who carried out quality control found that the excellent accuracy and precision of Swiss watchmaking companies was reflected in the 106 fuses’ performance.

Although the Swiss were held to be neutral, there were some scandals when one side was treated more favourably. One of the worst was the 1916 ‘Two Colonels Affair.’ Carl Egli and Maurice de Wattenberg had been sending intelligence reports and sensitive material to the Austrian and German Attachés in Switzerland for a year. They had intercepted traffic between foreign embassies and their governments. When the Swiss government found out, they were told that the officers had received information in return. The officers were sacked, but no further action was taken.

Many exiles came to Switzerland, including Czechs and Lithuanians who sought independence from their ruling overlords. King Constantine of Greece, Lenin and Trotsky were exiled there. It was from Switzerland in 1917 that the German sponsored ‘Sealed Train’ took Lenin to Sweden and allowed him to get to Russia and help organise the revolution that took Russia out of the war.

The Swiss Army had a military tradition. In medieval times, Swiss mercenaries were much sort after and the Swiss are also associated with the guarding of the Vatican. The Swiss Army’s last action had been in the Sonderbund (Civil War) in 1847. The Army was subsequently only mobilised twice against possible incursion. Once was when Prussia threatened invasion in 1856-57 and during the 1870-71 Franco- Prussian War. (Photo right - Swiss volunteers)

Out of a total population of 3.5 million, there were 220,000 front line troops and 250,000 reserves. The Army comprised 8 Divisions to cover its borders. There were 240 Officer Instructors and 100 fortification maintenance soldiers. The rest were conscripts aged 20-48. Initial training lasted 50 days with biennial two week refreshers. After 12 years, they joined the Landwehr (Reserves). Men aged 17-50 were eligible for the Landsturm (Militia) and to enable quick reaction, soldiers kept their rifles at home. (A practice still in use today but now the ammunition is kept in armouries). Officers had to initially serve in the ranks. The Army modernised as the war progressed and had some modern weapons. The uniform was changed from dark blue to field grey and a steel helmet similar to the French ‘Adrian’ was subsequently introduced

Frontier guards were kept up to strength well after the threat subsided, which caused some resentment in the ranks. Fear of invasion by belligerents, especially in the north-west using Switzerland for outflanking movements meant some places had strong defences, including bunkers and wire. In quieter sectors, there was little fortification. A Front totalling 870 miles was difficult to protect and there were one thousand violations during the war. All belligerents were interred, including some pilots of aircraft forced to land on Swiss soil.

Two Serbian soldiers escaped from a German farm in 1916 and 13 days later got into Switzerland. One British soldier, AJ Evans, arrived from Germany and one known casualty was a Russian soldier shot by the Germans whilst attempting to cross into Switzerland. It was estimated 9,000 German deserters fled to Switzerland.

Some areas near the borders suffered bombing. After German bomb damage to houses in Porrentruy, the town was forced to place a huge cross on the ground to show it was within Switzerland. Aircraft from France, Italy, Germany and Austria-Hungary were all liable to fly over Swiss soil.

Two French airmen, Sergeant Madon and Mechanic Corporal Chatelain, who had landed inadvertently and had not given their parole not to escape, managed to abscond. On 7 October 1918, a clearly marked Swiss observation balloon was shot down by a German aircraft and the observer, Lieutenant Walter Flurry, was killed, which created tensions.

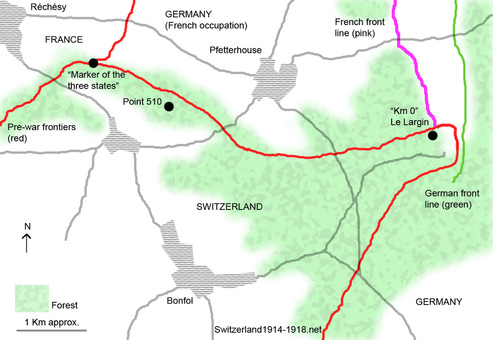

The Three Nation border at the southern end of the Western Front was relatively quiet. After the Franco-Prussian 1870-71 War, Germany (by then a unified state) had occupied French Alsace-Lorraine. By the end of 1914, at the southern part of this, the French had pushed into what was then Germany. This was the only part on the Western Front where the trenches were on German soil. Naturally, the French regarded this as taking back what was theirs and fought hard to retain it. Due to an anomaly in the national boundaries, the French southern trenches hit the Swiss border which ran west to east.

This was known as Kilo Zero. However, the Swiss boundary had a small protrusion (known as the Duck’s Beak) at its eastern end which meant the German lines continued slightly further south. (See map).

At the point where the three nations met in the west, there were 3 marker stones marking each country’s border. An interesting incident occurred. It was not far from this point that on 2 August 1914, one day before France and Germany were officially at war, that the first casualties of the conflict took place. Shots were exchanged between a German patrol that had crossed the French border and French sentries. The commanders of the two detachments, French Corporal Jules Andre Peugeot and German Lieutenant Albert Otto Walter Mayer, were both shot and killed. Generally, the frontier near the Duck’s Beak was relatively quiet.

Swiss army helmet, used from 1918 until post WWII (Swiss Federal Archives)

Alsace, the region stretching roughly 100 miles north from the Swiss frontier, had been absorbed into the German Empire in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War. Therefore in 1914, the French were determined to recover this territory. In the first month of the First World War, the French army managed to advance until they captured the city of Mulhouse (about 20 miles km north-east from this part of the Swiss frontier), but were swiftly forced back by a German counter-attack and the front lines then stabilised. The French retained control of the village of Pfetterhouse. On the German side, Moos was the nearest village. The two sides faced each other from either side of the valley of the Largue River.

As on the rest of the Western Front, a system of trenches grew up behind the front lines. After 1914, there was no longer any heavy fighting next to the Swiss frontier, but the vicious battles in the Vosges Mountains took place some 30 miles to the north. Like many other nations, Switzerland had difficulties after the war ended and in 1929 joined the League of Nations.

Terry Jackson