Chairman’s Comments

Strange Times!

In normal circumstances, this Friday the 17th was supposed to be our April meeting but the world changed forever in the weeks just before our last 13th March meeting!

Just a week prior, I checked with Les at the TA centre and our speaker, Dr Jessica Meyer, if they were okay for our meeting to proceed with the emerging uncertainty in the air. I, like everybody, was certainly worried about the level of threat to normality but the virus was already beginning to affect our population. It was evident as the week passed that the UK was on the brink of a disaster of epic proportions. The Covid19 virus onset had already taken its toll in Europe and more was to come. By the time of the meeting I had my own misgivings and the media frenzy during that week had given me more than enough to put doubt in my mind about going ahead. I expected a very poor turnout but twenty-eight attended and made it seem quite normal. All went well and we seemed to have got away with it, but unfortunately I had to announce the cancellation of the next three month’s meetings. I’ve since cancelled July as well but let’s hope things will have changed for the better by mid- July. We have our star speaker John Derry booked in August and I hope the lockdown will have ended to enable his visit.

As reported in the recent edition of Bulletin, the WFA cancelled the Spring Conference and AGM arranged for 25th April in Leeds. Please fill in and return the AGM notice flyer to the Hon Sec with your proxy vote on the four resolutions. By post or scan and email. Your voting form is appreciated.

Also cancelled is the Presidents Conference scheduled for 23rd May in Birmingham and all of our UK Branches have suspended their summer programme of meetings. To keep our Branch going from afar I have arranged with the relevant speaker to submit an article for an April edition of ‘Up the Line’. This based on his proposed talk. Stephen Roberts has given us a soldier’s story showing the hard times suffered by their families. I will do the same until our meetings start again. Terry Jackson has kindly volunteered to provide an article for each edition during our shutdown. As editor of the WFA Bulletin I was pleased to complete the production and distribution of the latest edition (116) which most members will have received last week. I hope this gives you some interesting reading.

I also recommend you look at the WFA website and I can particularly recommend the WFA YouTube section for video presentations by numerous historians speaking at WFA events and the Podcasts of which 140+ have been produced and made available by Dr Tom Thorpe, WFA Trustee.

Although the centenary years of the 1914/1918 conflict have passed, we will continue to be interested in this war that altered the futures of so many people and families, directly affecting all the population of the UK and its Dominions. The many aspects of this war will continue to be discussed for a long time to come. Our monthly meetings will recommence asap.

Ralph Lomas

A Land Unfit for Heroes:

The Sufferings of Great War Veterans in the North-West of England in the 1920s from Letters sent to the Earl of Derby of Knowsley Hall:

The Earl of Derby and His Letters

The Earls of Derby descend from a branch of the Stanley family, which has played a big part in English history since the middle ages. They began in Staffordshire, before moving to Storeton, Wirral, where a descendant became the Forester in the 13th century. In 1385 Sir John Stanley married into the Lathom family of Ormskirk and thereby initiated the family’s rise to power in Lancashire. Thomas, Second Baron Stanley, was given the title Earl of Derby in 1485 as a reward for assisting Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth. Successive Stanleys were amongst the richest and most powerful aristocrats in the land. The 14th Earl was the longest serving head of the Conservative Party and three times Prime Minister. The 17th Earl was Edward George Villiers Stanley (1865-1948), who was a soldier, politician and cabinet minister, serving as Secretary of State for War in the Lloyd George Coalition Government between 1916 and 1918. (Photo right)

The Earl is credited with the creation of the Liverpool Pals and the Liverpool Dock Battalions, as well as being associated with local Territorial units – the Fifth and Sixth Battalions of the King’s (Liverpool Regiment) – before initiating the Derby Scheme in 1915. During the first year of the Great War, by leading recruitment campaigns and acting as patron and benefactor to the aforementioned regiments, Lord Derby became a symbol of Merseyside’s involvement in the conflict. He even invited the Pals to train on his grounds at Knowsley Hall. During his many addresses to the troops before they left for the front, he often reminded them that they were fighting to defend their homes and families and would return as heroes to a grateful land. In 1922, in Morecambe, he went a step further and announced that any veterans who were not receiving their promised pensions should contact him for help and he would approach the ministry on their behalf. Embarrassingly for him and his staff, a great many unemployed, impoverished, sick and disabled ex-soldiers, mainly from Lancashire, interpreted this as an invitation to ask him for financial help if they were in need. Consequently, they wrote to him in their hundreds, outlining their pitiful and heart-rending circumstances and respectfully trying to hold the Earl to his word. Most of them were rejected with a curt standard letter from his private secretary; a minority of cases were investigated and resolved.

The Veterans’ letters were preserved and are now lodged at the Liverpool Record Office. They contain details of struggles which should never have been necessary, as these unfortunate people cried out for help. The promises made to the soldiers were not kept and the land was clearly not fit for heroes. As it is now the centenary of the post-war period, it seems fitting that we should look into the lives of our soldiers during those difficult years and discover who they were, what they went through and whether they ever won their battles against disability, illness and poverty or were ever able to lead anything like normal lives again. By analysing the letters and tracing their authors and their families, my aim is to bring the veterans, their neighbours and relations to life and thereby to offer insights into the medium-term impact of the Great War on British society.

Stephen Roberts

Sergeant Charles Speakman, Loyal North Lancashire Regiment

Recently, I discovered the papers of the 17th Earl of Derby in Liverpool Archives. They are voluminous and, upon being deposited in the archive were apparently chaotic. Some degree of order has been imposed, but serendipity is still possible and was exemplified by my discovery of several folders containing letters written to the Earl during the 1920s by ex-servicemen asking for help during the post-war slump. This was written during early February in 1922 by a working-class ex-soldier from Chorley in Lancashire and reads:

Kind Sir i write these few Lines hoping you will look into my case i am in a poor way for i have 4 little Childrens and a Wife to keep and i have been doing nothing for the last 9 months i had to pawn my DCM and my Other 3 War Medals for food for them and i do not no which way to turn i when through the War from 19-14 to 19-19 and then their were 6 Brothers of us and 3 was killed in 19-16 and i was wounded a few times and i have never had a pension i would be very please if you would look into my case for i have to turn my kiddies out many a day without any food and i do not know one day for the other i was a Sergent in the Loyal. N. L. Regt if i had been single i would have took on again i expect you look into my case for it is hard times for us now, yours faithfully, Charles Speakman, 14 Lyons Lane, Chorley, Lancashire

The Earl of Derby’s secretary, Mr Harrap, had pencilled some notes in shorthand at the foot of the letter and written in ink, ‘Draft Suggest Local Pension’. No copy of Harrap’s reply can be found and it is not known whether Ex- Sergeant Speakman received any help from his local pensions board.

The letter itself is a precious artefact – a record of a tiny moment in history, when an impoverished ex-serviceman addressed one of the most powerful aristocrats in England (the ‘King of Lancashire’ no less), on a tattered piece of paper, possibly rescued from a bin and upon which he probably wrote with a borrowed pen, on his foodless kitchen table. He expressed his agonies as well as he could in ungrammatical and yet respectful English and left us a provocation to further research. With the help of extant genealogical and military records we are able partly to reconstruct the story of Charles Speakman and his family during the era of the Great War and to learn more about the lives of Lancashire’s working-class, their contribution to Britain’s war effort and the effects the conflict had on their lives.

Charles Speakman was born on 7th November 1884 in Chorley, the son of Joseph and Elizabeth Speakman. Joseph had been born in Wigan in 1856 and Elizabeth in Bolton in 1853. When the couple had married in October 1879 in Wigan, Elizabeth was a widow with two sons – William and John Withnell (both born in 1876). The couple went on to have seven more children: Elizabeth (1881), Daniel (1883), Charles (the writer of the letter, 1884), Joseph (1886), James (1888), George (1891) and Mary (1893). In 1891 and 1901 the family was living at 16 Mill Street in Chorley. On both occasions, all the younger generation of working age were employed in cotton mills, while their father, Joseph Senior, was firstly a ‘General Carter’ and then a ‘Labourer in an Iron Foundry’.

The 1911 census gives more clues about the family’s living conditions. By then Charles was living in a four-roomed (‘two-up-two-down’) house at 8 Critchley Street in Chorley with his wife Jane (née Kellett, born in Bury in 1885), their children Elizabeth and Daniel and Jane’s widowed father, Daniel (aged 72). Charles was a labourer in a waggon works and Jane a carder in a cotton mill. At that time, Charles’s widowed father was also living in a ‘two-up-two-down’ dwelling at 18 Waterloo Street, along with his children, Joseph Junior (23), George (20), Mary (18) and John Withnell (33). Only Joseph Senior, Mary and John appear to have had jobs. Other family members lived nearby in similar homes and all worked either at coal mines or in the textile industry. The only other time, during the Edwardian era, when a member of the family’s doings impinged upon official records was in July 1910, when the Lancashire Evening Post reported that Joseph Speakman Junior had appeared in the Magistrates’ Court for fighting with James Entwhistle on Water Street, Chorley. Both were bound over ‘to be of good behaviour for three months.’

When war was declared in August 1914, the Speakman brothers were quick to respond. Daniel’s service records have survived and reveal that he joined the 10th Service Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, with the number 12770, in Chorley, on 1st September. Charles’s records have not survived, but, given that his service number was 12762 and that he sailed to France on the same day as Daniel – 31st July 1915 – it is highly likely that they signed on together and could even have served in the same company. George Speakman’s service papers have also survived and inform us that he joined the 9th Service Battalion of the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, with the number 16182, on 17th September in Chorley. Probably during the same month, if not earlier, James Speakman (with no service papers), joined the 7th (later 11th) Service Battalion of the East Lancashire Regiment (later to become known as the ‘Accrington Pals’) with the number 15673. He was one of 215 Chorley officers and men who formed ‘C’ (later ‘Y’) Company, which later received the soubriquet the ‘Chorley Pals’. See photo borrowed from the Chorley Pals Memorial Website. It shows the men parading outside Accrington Technical College in September 1914. James must be one of them. It is easy to generalise about why working class men joined the forces with such alacrity in 1914. It is certainly probable that military service was seen as a desirable alternative to the low-paid drudgery of life in an overcrowded industrial town and as an opportunity for travel and adventure. The power of working class patriotism must also be considered, but, ultimately, in the words of Catriona Pennell, there were probably ‘as many reasons for joining up as there were men who joined up’. Whatever their motivations had been for becoming soldiers, it is certain that the British establishment benefitted from the enthusiasm, bravery and resilience of millions of working class recruits, whom it is quite possible to argue, owed nothing at all to the ruling classes who now sought their services.

The Speakman brothers’ military records imply that they were all good soldiers. George was promoted to Lance Sergeant on 11th May 1915. Daniel became an ‘unpaid’ Lance Corporal in February 1916 and, as we know, sometime later, Charles became a sergeant. Indeed, in November 1916, Charles was awarded one of the highest medals for bravery – the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). The citation reads:

For conspicuous Gallantry in Action. When in a crowded trench he noticed smoke issuing from a box of bombs. He seized the box and threw it over the parapet where it immediately exploded thereby undoubtedly saving many lives

In addition Charles was wounded several times. As he also stated in his letter, three of Charles’s brothers died during 1916. George fell on 2nd May while his battalion was in the frontline trenches near Givenchy in Northern France. The battalion war diary does not mention his name; he is simply listed as the one ‘other rank’ who was killed on that day. He is commemorated on Bay 7 of the Arras Memorial. Daniel Speakman died on 2nd July whilst a prisoner of war in Croisilles, having been captured and wounded the day before. The battalion war diary states that the 10th Loyal North Lancs had been supporting the diversionary attack on Gommecourt, by the 46th and 56th Divisions, to the north of the Somme Front and had experienced only ‘light’ casualties. Daniel Speakman was not mentioned by name. He is buried at H.A.C. Cemetery, Ecoust St. Mein in the Pas de Calais (ref. VIII.A.5).

James Speakman fell on 1st July near Matthew Copse, opposite the village of Serre, at the top end of the Somme Front, during the Accrington Pals’ ill-fated attempt to capture the village at just after 07.30 on that day. He is one of the thirty-one Chorley Pals (men from ‘Y’ Company of the Accrington Pals) who were killed, out of a total of ninety-three casualties in a company which had numbered 175 at the start of the attack. His body was never recovered and he is named on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing (Pier and Face 6.C).

To begin with, the British press portrayed the attack on the Somme as a success, but soon the pages of local newspapers contained nothing but lists and portraits of the local young men who had fallen in the ‘Big Push’. The small windows of Chorley’s terraced houses were curtained while families sobbed around their kitchen tables, shattered by news of the loss of loved ones and neighbours. Over a century later, judging by the popularity of pilgrimages to the Serre Road Cemeteries and popular interest the Chorley Pals Memorial and similar endeavours throughout the country, it would seem that the pain has still not totally assuaged. The remaining soldiers, like Charles Speakman, who had lost brothers and comrades, simply had to carry on doing their duty until, if they survived the ensuing two and half years of increasingly costly fighting, they were discharged and returned home in 1919 or 1920.

Charles stated in his letter that, if he had not had a wife and children, he would have stayed in the army. Perhaps, in spite of it all, he enjoyed soldiering and knew he was good at it or perhaps he knew that as a soldier he was guaranteed an income – something which bitter experience had taught him might not be available in Chorley. As he subsequently made clear to Lord Derby, his fears had been well-founded, as by the time he wrote his letter to the aristocrat, he had been unemployed for nine months and had had to pawn his four precious medals. The post-war slump had killed Lancashire’s trade and industry. Thousands of ex-servicemen were laid off. Often hampered by illness and injury and in receipt of inadequate or non-existent pensions, many of them sought help from ex-servicemen’s associations, charities, local authorities, the government and the ruling class. Many fell by the wayside, dying of broken hearts, of disease and by their own hands, but many more, showing the same resilience they had demonstrated in the trenches, persevered and lived to old age. Charles Speakman was one of them. In 1939 he was living at his old address, 14 Lyons Lane, Chorley with his wife Jane and working as a ‘shell-filler’. Perhaps, what became known as the Second World War gave him six years of relative prosperity and the post-war Welfare State a reasonably comfortable retirement before he died, aged sixty-eight in 1952.

Stephen Roberts

Last Month’s Talk

Dr Jessica Meyer, Associate Professor, Leeds University gave the Branch an in-depth account of how wounded soldiers were treated on the Western Front

The first aid for a wounded soldier was his own dressing pack (photo right). These were very basic, but gave the soldier a degree of comfort. Casualties would either walk or be brought to the Regimental Aid Post situated in their trench lines and would receive initial first aid.

Regimental Aid Post (RAP)

The RAMC [Royal Army Medical Corps] chain of evacuation began at a rudimentary care point within 200-300 yards of the front line. Regimental Aid Posts [RAPs] were set up in small spaces such as communication trenches, ruined buildings, dug outs or a deep shell hole. The walking wounded struggled to make their way to these whilst more serious cases were carried by comrades or sometimes stretcher bearers. The RAP had no holding capacity and here, often in appalling conditions, wounds would be cleaned and dressed, pain relief administered and basic first aid given. The Regimental Medical Officer in charge was supplied with equipment such as anti-tetanus serum, bandages, field dressings, cotton wool, ointments and blankets by the Advance Dressing Station [ADS] as well as comforts such as brandy, cocoa and biscuits.

If possible men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground, and under fire, to the ADS, sometimes via a Collecting Post or Relay Post to avoid congestion.

Advanced Dressing Station (ADS)

These were set up and run as part of the Field Ambulances [FAs] and would be sited about four hundred yards behind the RAPs in ruined buildings, underground dug outs and bunkers. In fact, anywhere that offered some protection from shellfire and air attack. The ADS did not have holding capacity and though better equipped than the RAPs could still only provide limited medical care. Here the sick and wounded were further treated so that they could be returned to their units or alternatively, were taken by horse drawn or motor transport to a Field Ambulance. The Main Dressing Station [MDS] roughly one mile further back did not at first have a surgical capacity but did carry a surgeon’s roll of instruments and sterilisers for life saving operations only.

In times of heavy fighting the ADS would be overwhelmed by the volume of casualties arriving and often wounded men had to lie in the open on stretchers until seen to. ADS would also have comforts such as brandy, cocoa and bandages, field dressings, cotton wool, ointments and blankets. If possible men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground and under shell fire, to the Field Ambulance, sometimes via a Collecting Post or Relay Post to avoid congestion.

In times of heavy fighting the ADS would be overwhelmed by the volume of casualties arriving and often wounded men had to lie in the open on stretchers until seen to.

Field Ambulance (FA)

These were mobile front-line medical units for treating the wounded before they were transferred to a Casualty Clearing Station [CCS]. (Not an actual vehicle). Each Army Division would have three FAs which were made up of ten officers and 224 men and were divided into sections which in turn comprised stretcher-bearers, an operating tent, tented wards, nursing orderlies, cookhouse, washrooms and a horse drawn or motor ambulance. Later in the war fully equipped surgical teams were attached to the FA and urgent surgical intervention could be performed to sustain life. By the autumn of 1915 some FAs had trained nurses posted to them.

In these early stages men were assessed and then labelled with information about their injury and treatments. As in a Casualty Clearing Station, medical officers had to prioritise casualties using a procedure known as triage. Many of the wounded were beyond help; morphine and other pain killing drugs were the only treatment.

Female ambulance staff

Female ambulance staff

Casualty Clearing Station (CCS)

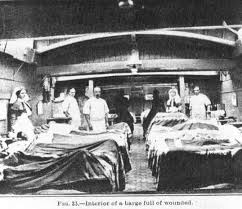

These were the next step in the evacuation chain situated several miles behind the front line usually near railway lines and waterways so that the wounded could be evacuated easily to base hospitals. A CCS often had to move at short notice as the front line changed and although some were situated in permanent buildings such as schools, convents, factories or sheds, many consisted of large areas of tents, marquees and wooden huts often covering half a square mile. Facilities included medical and surgical wards, operating theatres, dispensary, medical stores, kitchens, sanitation, incineration plant, mortuary, ablution and sleeping quarters for the nurses, officers and soldiers of the unit. There were six mobile X-ray units serving in the British Expeditionary Force [BEF] and these were sent to assist the CCSs during the great battles. CCSs were often dangerously vulnerable with large depots containing munitions and supplies alongside which were targeted by enemy aircraft and artillery.

A CCS would normally accommodate a minimum of fifty beds and 150 stretchers and could cater for 200 or more wounded and sick at any one time. Later in the war a CCS would be able to take in more than 500 and up to 1000 when under pressure. In normal circumstances the team would consist of seven medical officers, one quartermaster and 77 other ranks, a dentist, pathologist, seven QAIMNS [Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service] nurses and non-medical personnel. Major surgical operations were possible but sadly, men who had survived this far often succumbed to infection. The CCSs were usually in small groups of two or three to enable flexibility. One might treat cases for evacuation by train, ambulance or waterways to the base area, leaving one free to receive new casualties and another was able to treat the sick who could be moved, in order to receive battle casualties in an emergency.

Casualty Clearing Station

Casualty Clearing Station

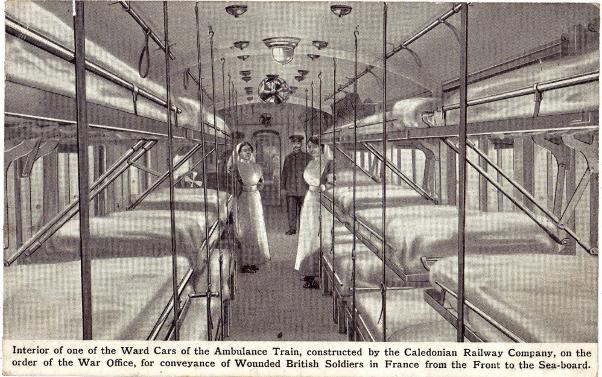

Hospital Train

Hospital Train

Initially the wounded were transported to the CCS in horse-drawn ambulances – a painful journey and over time motor vehicles or even narrow-gauge railways were used. Often the wounded poured in under dreadful conditions, the stretchers being placed on the floor in rows with barely room to stand between them. The admissions and evacuations were incessant and almost all that could be done in the time was to feed the patient and dress his wounds. One of the greatest boons was the provision early in 1915 of trestles on which the stretchers were placed. Comforts such as sheets, pillow cases and bed socks were obtained from such organisations as the BRCS [British Red Cross Society]. As the number of casualties grew, so the need for experienced staff increased. In the first Battle of Ypres difficulties were highlighted with an influx of between 1,200 and 1,500 casualties in twenty four hours and in the Battle of the Somme of July 1916 there were between 16,000 and 20,000 casualties on the first day of the offensive. By August 1916 selected CCSs had as many as twenty five nurses on the staff.

Hospital Barge

Hospital Barge Base Hosipital

Base Hosipital

Brighton IV hospital ship

Greek Street school Alexandra Park military hospital

Alexandra Park military hospital

Gas was first used at Ypres in April 1915 and thereafter as a weapon by both sides. Patients were brought in to the CCS suffering from the effects and poisoning of chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas amongst others.

The seriousness of many wounds and infection challenged the facilities of the CCSs and as a result their positions are often marked today by military cemeteries. Kate Luard (photo right) was posted to a number of CCSs including one as Head Sister of No.32 CCS which specialised in abdominal wounds and which became one of the most dangerous when the unit was relocated in late July 1917 to Brandhoek to serve the push that was to become the Battle of Passchendaele, and where she had a staff of forty nurses and nearly 100 orderlies.

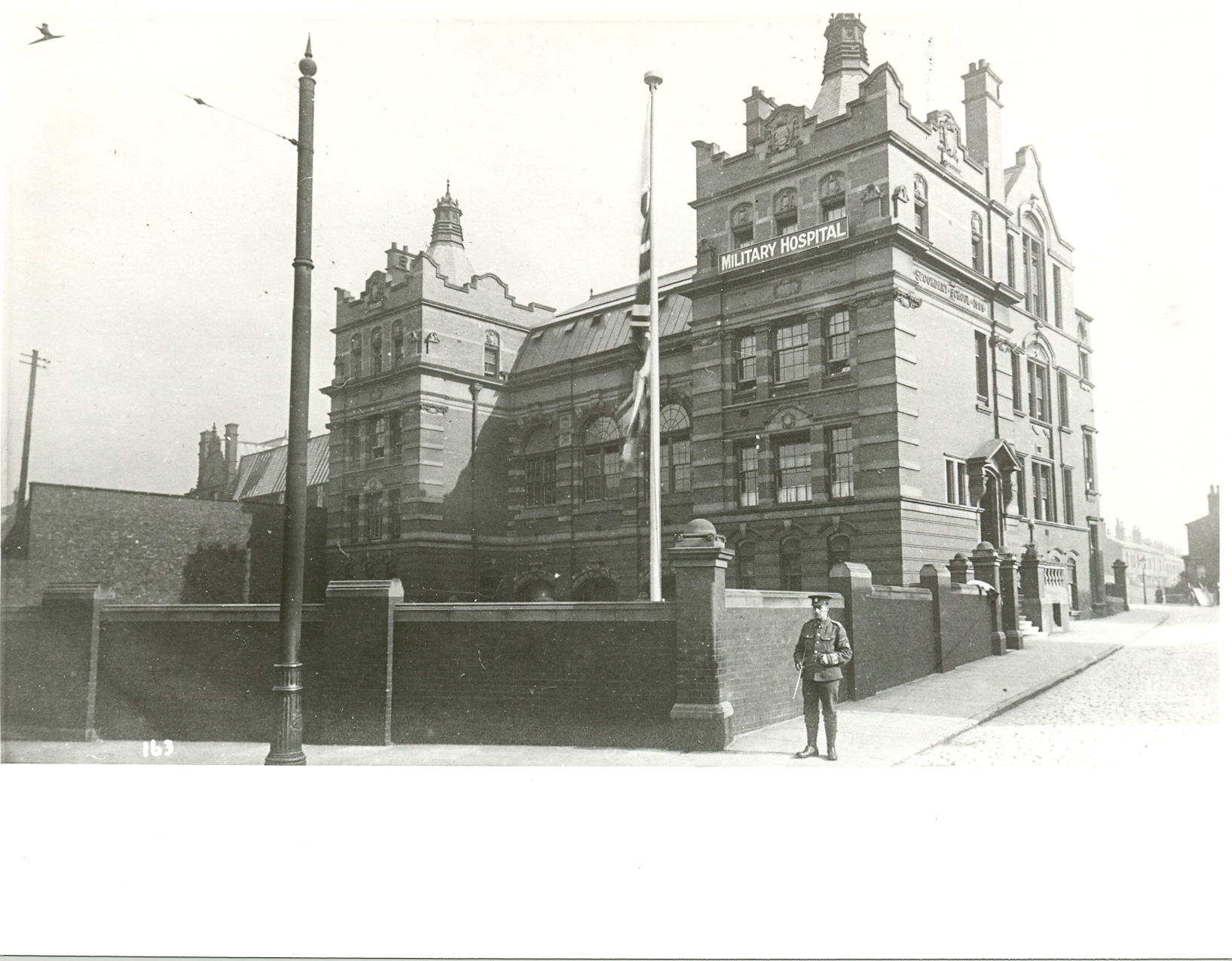

From the CCS men were transported en masse in ambulance trains, road convoys or by canal barges to the large base hospitals near the French coast or to a hospital ship heading for England. Back home men would be sent to a local hospital unless they needed specialist treatment. These would often be schools or similar institutions

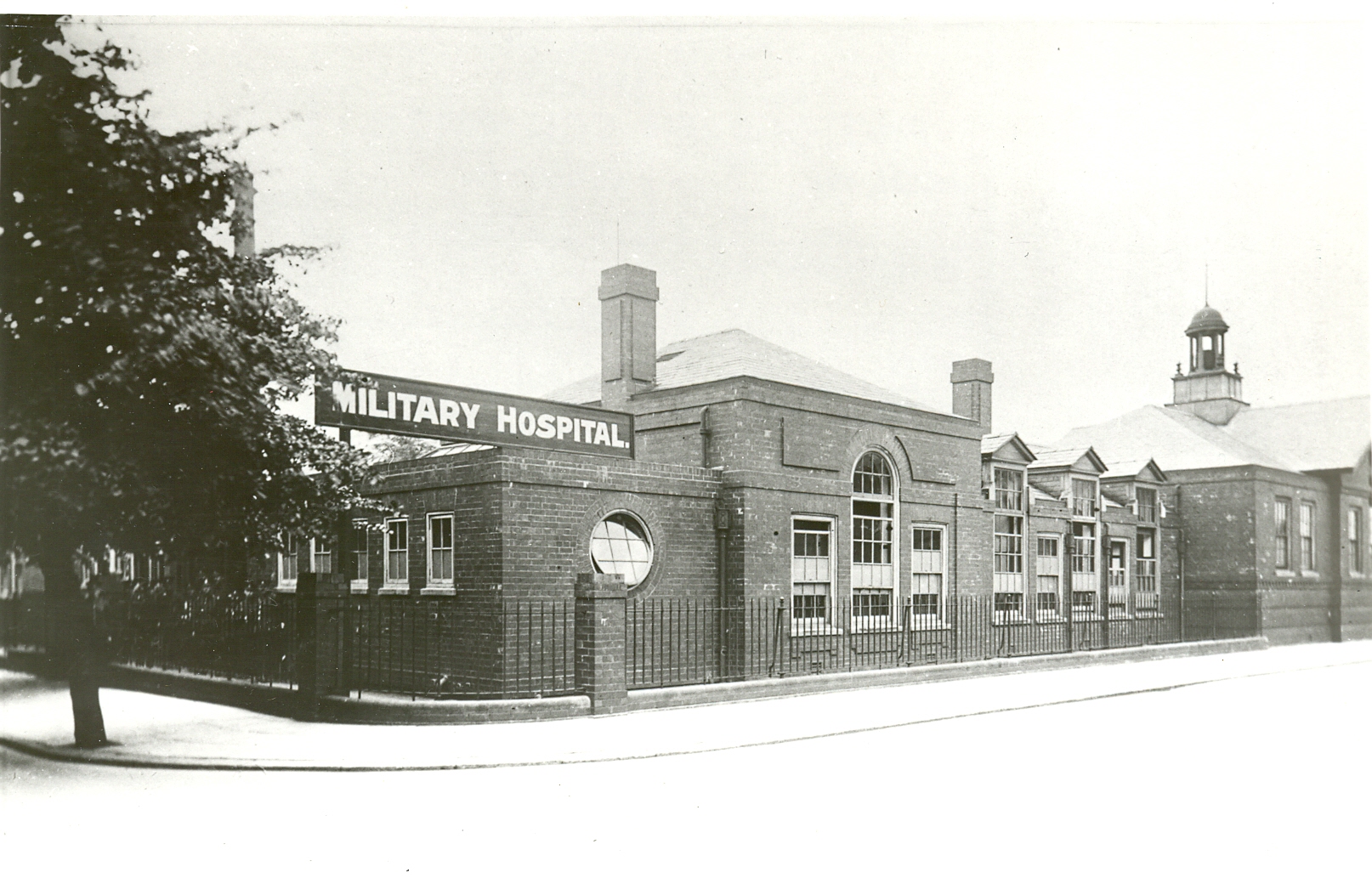

The Victorian Building on the junction of Greek Street and Royal George Street was used as a Military Hospital (diagonally opposite the TA) as was Alexandra School further down Castle Street.

The system worked for the early years after the relativity of static trenches but in the 100 days advance it was increasingly difficult to move the aid facilities forward to keep up with the progress of the front line units.

A fascinating study of probably the most essential non combative service in the Great War

Terry Jackson

PS Jessica Meyer's book on the RAMC in WWI can be read free of charge: go to this link and click on "open access".

Additional Article from Terry

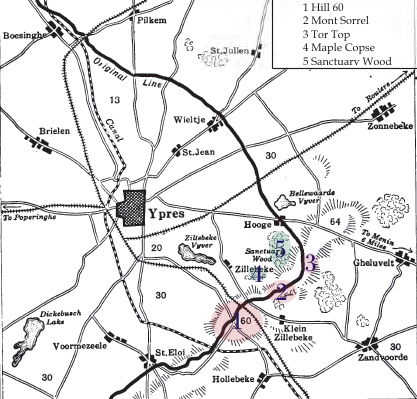

In view of the postponement of meetings due to the virus, I am looking at actions that occurred on the actual date of the meetings. The first is below and is a report on the Actions at Hill 60 which occurred just before the commencement of 2nd Ypres when gas was used for the first time. The report has been extracted from the National Archives.

Hill 60

1. Report on action at Hill 60, 17-21 April 1915.

2. Hill 60, a small, steeply-escarped hill, enabled the enemy to see into the ground behind the 5th Division lines, and was useful to him as an observation station. Its capture would strengthen position.

3. Mining operations had been begun in the early part of March by Major Norton Griffiths RE and the 171st Mining Company, whilst the 28th Division was holding the line which the 5th Division now holds.

It is due to the ability with which these mining operations were carried out that the assault on the hill was so immediately successful, and that the loss during the actual assault was small.

4. For some days before the attack, the 15th Infantry Brigade – then holding the trenches – were engaged in preparing positions to enable the assaulting columns to assemble.

The 13th Infantry Brigade who were in reserve and part of which under Brig. General R. Wanless O’Gowan was to carry out the assault, were employed in rehearsing the assault on plans of our own and the enemy’s trenches, spitlocked out on the ground.

5. During the night 16th/17th, troops destined for the attack (2nd KOSB, 1st Royal West Kent Regt, and 2nd Home Cos. Co. RE), under command of Brig. General R.Wanless O’Gowan, were moved into position.

Mines were exploded at 7pm on April 17th, and the assault immediately took place and was successful. (Operation Order No.50 of 5th Division attached.)

6. Severe fighting ensued all night. The enemy kept up a constant and heavy artillery fire and attacked incessantly, using hand grenades freely, and with great effect.

At 1.30am on 18th, the Officer Commanding 1st Btn Royal West Kent Regt who had carried out the assault, reported that he had firmly established a good fire trench on the hill and dug two good communication trenches.

7. At 3.30am, the 2nd Btn KOSB relieved the 1st Btn Royal West Kents in the new trench. Owing to casualties amongst several senior officers at the time, it would appear that a little ground was lost during this relief.

At [in pencil – 5.30am] the 18th two companies of the 2nd Btn Duke of Wellington’s Regt were pushed up from ZILLEBEKE pond to the trenches, and were replaced at the latter place by two companies of the 2nd Btn KOYLI from YPRES.

8. At about 7am, from reports received it appeared to me that our troops had been pushed from the crest of the hill. I informed the GOC 13th Infantry Brigade that, if the hill had been lost, it must be recaptured and that all available reserves are placed at his disposal for this purpose. (Telegrams G.393 attached).

About this time the 9th Btn London Regt was ordered to march from OUDERDOM to YPRES and the 1st Btn East Surrey Regt at KRUISSTRAAT were directed to hold themselves in readiness to move.

Both these battalions were placed at the disposal of the GOC 13th Infantry Brigade.

By 7.30 am, the 2nd Batn Duke of Wellington’s Regt had reached the front and were engaged in relieving the 1st Batn Royal West Kent Regt and the 2nd Batn KOSB; the latter two battalions were afterwards withdrawn into reserve.

9. During the 18th, our troops held their positions on the Hill under a tremendous bombardment and constant attacks by hand grenades but were slowly pushed back below the crest.

Brig. General Wanless O’Gowan considered a counter-attack should take place in the evening. In this I concurred, stating that I considered it better that the attack should take place that evening rather than later when the enemy could have had time to strengthen his position. Orders were issued for the recapture of the crest.

The Bedfordshire Regt (15th Infantry Brigade) and the 1st Btn East Surrey Regt (14th Infantry Brigade were ordered forward during the afternoon to take the place of the 1st Btn Royal West Kent Regt and 2nd Btn KOSB).

The 59th Field Company Royal Engineers were also placed at the disposal of General Officer in Command, 13th Infantry Brigade and were employed throughout the remainder of the operation.

10. At 6pm, (instead of 5pm as originally arranged) on the 18th, the hill was again attacked, the assault being carried out by the 2nd Btn Duke of Wellington’s Regt and the 2nd Btn KOYLI, and at 6.55 pm the hill was once more held in strength by us.

11. At 11.30 pm, the position of the 2nd Btn Duke of Wellington’s Regt and the 2nd Btn KOYLI on the hill was now satisfactory and that they were firmly established, but that the losses had been heavy and the men were a good deal exhausted.

It was ordered that these battalions should be relieved by the 1st Btn East Surrey Regt, 1/2 Btn 1st Bedfordshire Regt and the 9th Btn London Regt, and that on completion of relief Brig. General E. Northey should take over command from Brig. General R. Wanless O’Gowan.

This relief was successfully accomplished.

12. During the 19th, the hill and vicinity were held by the 1st Btn Bedfordshire Regt, 1st Btn East Surrey Regt, and 9th Btn London Regt, under a bombardment of tremendous intensity; officers who have served throughout the war describe it as the heaviest they have experienced.

Terry Jackson

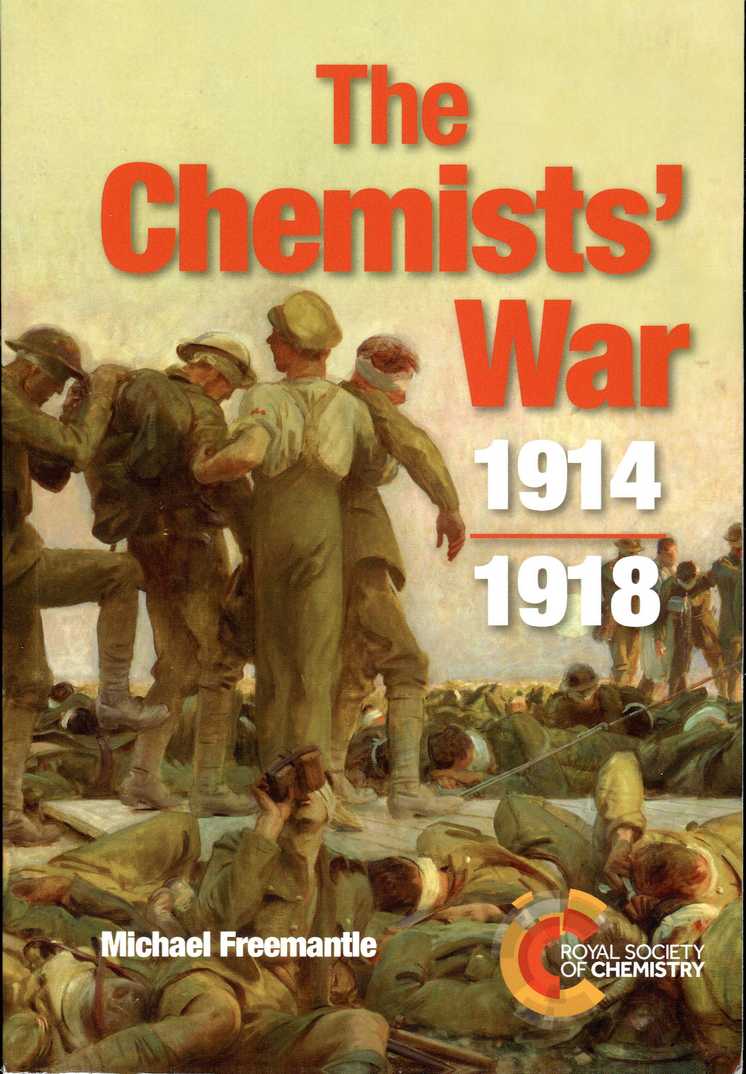

Book Review

The Chemist’s War 1914-1918

Michael Freemantle

Royal Society of Chemistry, London, 2015

This book was a prize in a WFA raffle, the previous owner having been none other than John Richardson of the Stockport branch, a former national committee member.

WWI was in many ways the first technical war. Rob Thompson always says it was an engineers’ war, and to that I would add the chemists.

The big advances in explosives happened before WWI but had major impact, as it were, during the war. Nitrate-based explosives, both as propellants and as explosive charges, were developed in the 1880 to 1914 period. The importance of nitrate is that it is composed of nitrogen and oxygen atoms which will decompose to give two very stable molecules, that is oxygen gas (two oxygen atoms linked by a double bond) and nitrogen gas (two nitrogen atoms linked by a triple bond). So, going to two very stable entities means that a lot of energy is released.

This facilitated the development of rifle cartridges that propelled the bullet faster and with a flatter trajectory. Shells went further and had a bigger bang. This made possible the modern rifles used in WWI and the machine guns and fast firing artillery. The book gives details on the chemistry and metallurgy of the Lee Enfield round, as one example. These developments swung the balance from the attacker to the defender well before WWI, a development not understood by the military leadership of any of the eventual protagonists of WWI. So, the strategy and tactics of the war, especially in 1914 were fatally flawed on all sides – fatal especially for the soldiers of all sides.

That brings us to a key character in the book – Fritz Haber. He was an eminent German chemistry professor and arguably the most important figure in chemistry in the 20th century. In 1909, he developed a method for producing ammonia from nitrogen (which is present in air) and hydrogen. Nitrate can be made from ammonia. Carl Bosch turned Haber’s research into an industrial process. In 1913, BASF starting making ammonium nitrate near Ludwigshafen, primarily as an agricultural fertiliser. Haber was awarded the 1918 Nobel prize for chemistry. In WWI, ammonium nitrate production was turned to military purposes.

The less happy side of Haber is that he is seen as the father of chemical warfare. The author details the development of chemical warfare in WWI from the crude beginnings of using chlorine, which was not very effective, through to mustard gas, which was. The use of poison gas was a leapfrog between the Germans and the Entente, in that one side would use a new gas, and the other side would produce a new gas mask to counter it. The game changer was mustard gas which could be absorbed through the skin and did not blow away in the wind. The first use of mustard gas in 1917 by the Germans produced results which astounded both Haber and the army command. The author points out that gassing was rarely fatal, as only 1.5% of the casualties died. Indeed, the “justification” for using gas which was put forward by protagonists such as Haber was that it caused fewer casualties than an artillery barrage would have done.

The author points out that, in modern times, Saddam Hussein used gas attacks in Iraq, but omits to say that the RAF used gas against Iraqi civilians first, in 1924. The author describes an obscure incident in WWII at Bari in Italy when an American cargo ship, which was loaded with a secret cargo of mustard gas bombs, was damaged in an air raid. Some of the gas escaped, and poisoned sailors and civilians. The medical staff did not know initially that they were dealing with mustard gas, so many people died. The tragedy was hushed up both during WWII and for many years thereafter.

The positive use of mustard gases was their use as anti-cancer agents. This was the beginning of cancer chemotherapy. Post-war uses of poison gases include the development of anti-oxidants to preserve rubber, and foodstuffs. Others have been used as pesticides, for example in grain silos.

Other aspects of the war dealt with in the book include the following. Have you heard of the 1915 shortage of artillery shells? Well, it was actually a shortage of acetone, a solvent used to make cordite. Chaim Weizmann, later a Zionist politician, developed a fermentation method to make acetone from plant material. Robert Robertson changed the method of production of cordite to make “cordite RDB”, which was produced using alcohol, from late 1916. The alcohol came from British distilleries. Robertson was a Scot!

Another, happier, use of technology was aboard hospital ships. Henry Dakin suggested the installation of a water tank in which sea water could be electrolysed, that is an electric current passed through it. The product is a solution of sodium hypochlorite, a disinfectant. The provision of unlimited quantities of disinfectant improved wound and disease treatment aboard the ships. Dakin was also responsible for Dakin’s solution, a mixture of sodium hypochlorite and boric acid used to treat wounds by flushing the wound frequently with the solution. This was widely used to treat wounded soldiers.

Overall, the author has produced an authoritative book on many aspects of the chemistry used in WWI. WFA veterans may find the passing remarks to wartime events a tad superficial but the point of this book is the chemistry and the men and women behind it.

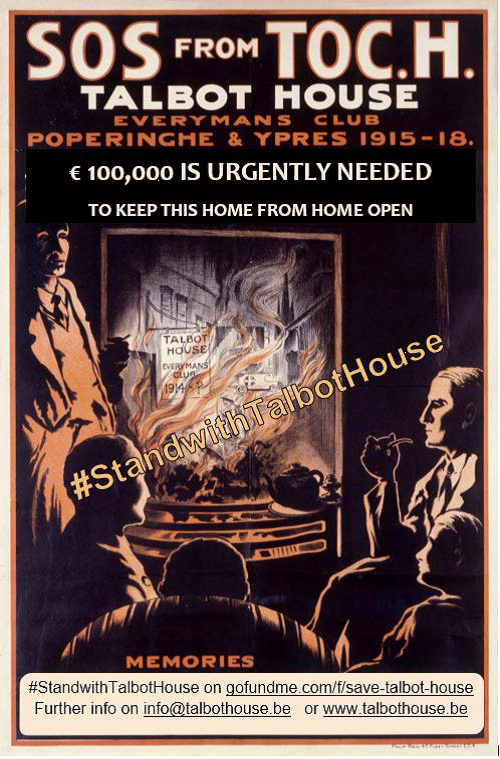

Save Talbot House Fundraising to keep historic WW1 soldiers club open

The Every Man’s Club

In December 1915, British army chaplains founded a club in Poperinge, Flanders. Their goal was to create a home from home for over half a million weary and homesick troops that were in the area. Here, they could meet up with friends regardless of rank, have a cup of tea, write a letter home, enjoy a well-kept garden or play the piano. In the attic, a chapel offered some comfort and provided hope for the men who had to return to the trenches. The club was so successful that soon after the war, some 500 TocH clubs sprang up throughout the Commonwealth. Since the reopening of the club in 1931, it has served as a living museum where one can also stay the night. Every year, thousands of pilgrims and tourists find a warm home from home and a cup of tea, like the soldiers back then. It’s an authentic British pearl from the war years. Last winter, work on a new permanent exhibition commenced. In ‘A House of People’ countless new tales of our rich history are told linked to some 500 artefacts from our collection, most of these never having been shown to the public before.

Shut Up!

Since 1930, Talbot House has been owned by a small non-profit charity and run mostly by volunteers. The major investment in our new permanent exhibition, paid out of our own pocket, and the forced closure due to the corona outbreak, has left us without an income, which is no less than a financial nightmare. With cancellations till the autumn, we see our income fade away. A historic House of more than 250 years old requires almost constant maintenance and renovation. As things stand at the moment, it is going to be a struggle to make it till the end of the year. When in the spring of 1918, our founding father Rev. Tubby Clayton was about to be evicted due to the advancing German forces, he didn’t give in without a fight. Several eviction orders followed, to which he invariably replied “Shut up!”, before he was eventually forced to set up a new club in a few huts in a meadow amongst the cows; incidentally, the hut he lived in is part of the new exhibition. Talbot House doesn’t close quietly…

We certainly have no intention to throw in the towel easily these days. A new campaign has been launched to save the House. In the first few hours, some 6,000 EUR has been donated. The funds will help us to survive while we have to remain closed, keep the House in good shape and help us to bridge the gap till we have sufficient income from visitors and guests again. In exchange for a donation, we offer all sorts of rewards ranging from free overnights stays and story tours to free breakfasts and membership of our Talbotousian family.

The future

Just like after the liberation in 1944, we hope to welcome everyone once again after a period of forced closure, this time with a brunch guests can sign in on. Obviously no date can be set for now, but together we can overcome this crisis. Talbot House has a lot of plans for the future still. Our new permanent exhibition needs to be officially opened, new story tours for groups and schools launched and a new virtual guided tour for individual visitors is in the pipeline.

In the meantime, we try to keep the club open ‘virtually’ with lots of films and stories of the House on our social media. That way, everyone around the world can enjoy the club. We hope you too can help us convince people to support our appeal so that we can preserve this precious piece of heritage for future generations. We remain available for questions, photos and interviews. The crowdfund campaign can be found on GoFundMe.

Simon Louagie, Talbot House Manager