Chairman’s Comments

This coming Friday we welcome Military Historian and WFA Hon. Vice-President, Mungo Melvin, who, I’m sure, will give us an interesting talk on his research and travels to the battlefields of WW1 to investigate what the modern British Army could learn from it.

As our meeting comes to order, but most importantly when the speaker commences his talk, can I respectfully ask that all members turn off their mobile devices until after Q&A’s have finished.

Joan continues to do great job with the raffle and she has enabled an increase in the quality of the book prizes as well as the odd ‘special’ prizes. Any donations of bottles of wine, chocolates and boxes of biscuits, greatly appreciated. Please liaise with Joan.

We have yet to hold an AGM to cover the year 2018/2019 so we will do this as expediently as possible at the 9th August meeting. The meeting will start at 7.45pm prompt so please try and arrive in good time. We don’t wish to delay John Derry’s much anticipated ‘Aftermath’ talk. The AGM needs to approve the 2018/2019 accounts, available at the door this Friday, also to re-confirm continuance of the current Branch committee members and consider any new volunteers.

Currently we have myself as Chairman, Andy McVeety as Treasurer, Joan Tomlinson as Social/Raffle Secretary and Phil Hamer General Support. We also have Terry Jackson as Branch Website Editor and Trevor Adams, Branch Website Manager, ensuring we maintain an online presence. Neil Morrow is our national website editor ensuring our branch speakers and talks are regularly updated. Anybody wishing to be the next Chairman or just come on the committee please speak/email myself asap. If you have any questions or complaints please contact myself asap. Tel: 01625 511645(W) or Email:

May I repeat the purpose of the WFA and these Branch meetings. First remembrance and with this the WFA’s intention to educate, or promote education, about the Great War to the general public, both young and old, unfortunately the latter seems to be more prominent, but that’s the way it is. The WFA try to do this through its magazines, website and conferences but most significantly its network of Branches throughout the UK and overseas. We currently have 53 branches throughout the UK. The WFA have just under 6000 members who have paid all £29 each to tap into the network and receive the two publications, Bulletin and “Stand To!”

This will be the fourth meeting of our fiscal year and I can report that we now have speakers arranged right through until next May with John Derry, Peter Hart, Jack Sheldon, Clive Harris and Rob Thompson taking us up to Christmas. As good a list of top military historians as you’ll see anywhere?

May I remind you that the 8 November meeting includes our usual brief but meaningful remembrance ceremony at 7.45pm.

Please also be advised that the December meeting will be on the first Friday (6th) not the usual second so a note in your diary please. Last year various members cried off due to office parties etc therefore a change seems to make sense.

The 6th December meeting has historically been a special social night with a hot-pot supper/glass of wine after the speaker. This year we intend to change to a buffet supper with wine and soft drinks also available, and I hope, with Rob Thompson as our guest speaker, we will have a good turnout of members.

Ralph Lomas

Speaker Profile

Major General Mungo Melvin CB OBE MA. Mungo Melvin retired from the British Army in 2011, having served in the Royal Engineers and on the General Staff. As a reservist, he advised on the First World War centenary commemorations. He is a senior visiting research fellow of the War Studies Department of King’s College London and a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute. Emeritus President of the British Commission for Military History, he is an Honorary Vice President of the Western Front Association and Chairman of the Royal Engineers Historical Society. Mungo edited the British Army’s Battlefield Guide to the Western Front of the First World War (2015); authored Manstein: Hitler’s Greatest General (2010) and Sevastopol’s Wars: Crimea from Potemkin to Putin (2017); and has contributed to many other historical works. Since 1992 he has designed and run a series of battlefield tours and staff rides.

Last Month’s Talk

Major Paul Knight PhD VR gave the Branch a detailed account of the campaign in Mesopotamia. Whilst the Western Front and Gallipoli have been considerably studied, the Middle East has, in modern times, been the centre of world political attention. The area then known as Mesopotamia has tended to be regarded historically as a backwater area. However, several future political and military icons were to serve there. This included Clem Atlee, Wavell, Slim and Hobart (he of the ‘Funnies’).

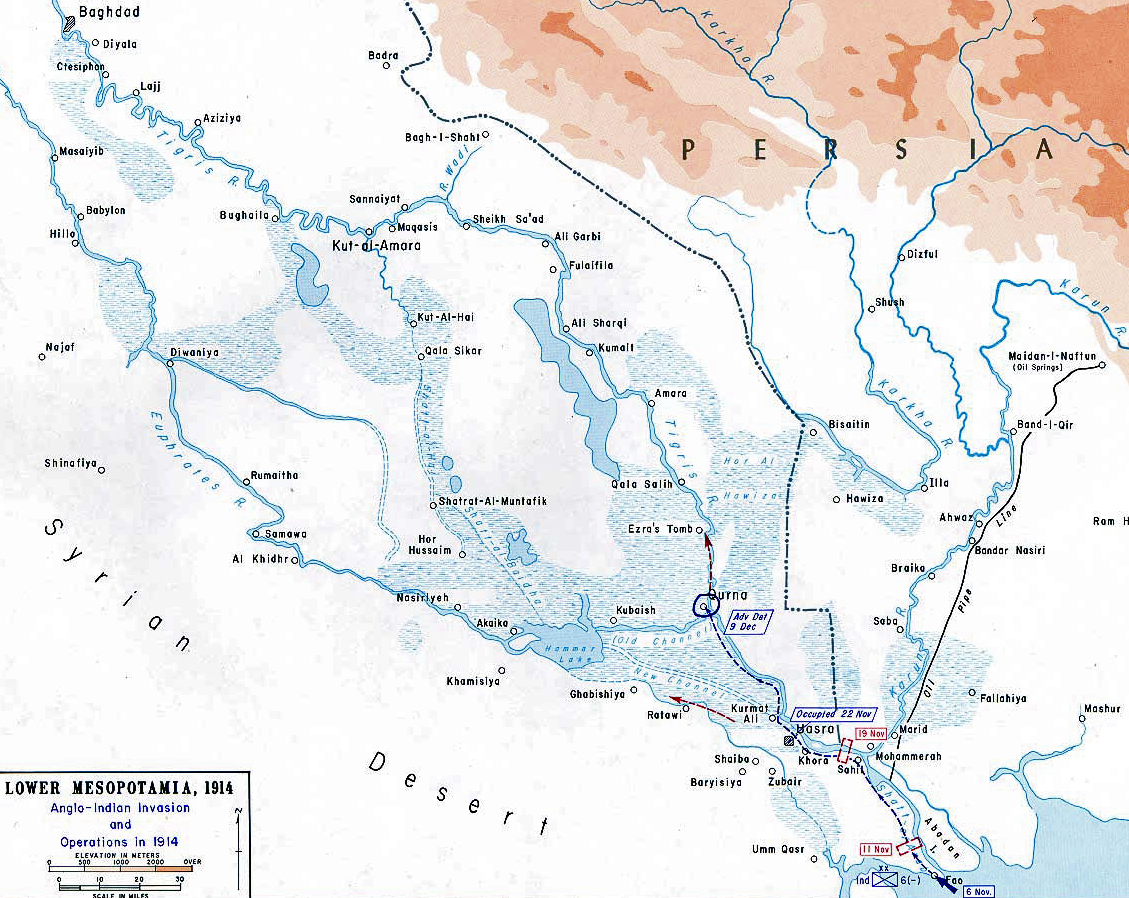

After Turkey entered the war on Germany’s side, Britain sent troops to protect its oil supplies in the Ottoman province of Mesopotamia. In November 1914, an Indian division occupied the port of Basra. Later a second division arrived and the British commander, General Sir John Nixon, advanced deeper into Mesopotamia. Britain believed a successful campaign here would help rally the Arabs against the Turks.

One division moved up the River Euphrates to Nasiriya. The other - the 6th (Poona) Indian Division- under the command of Major-General Charles Townshend - advanced 100 miles along the River Tigris to Amara, capturing it on 4 June 1915. From Amara, Townshend was ordered to push on; first to Kut al Amara and then to Baghdad, the provincial capital, some 250 miles away. His division entered Kut on 28 September 1915, having inflicted heavy losses on the Turks. By mid-November, it was only 25 miles from Baghdad.

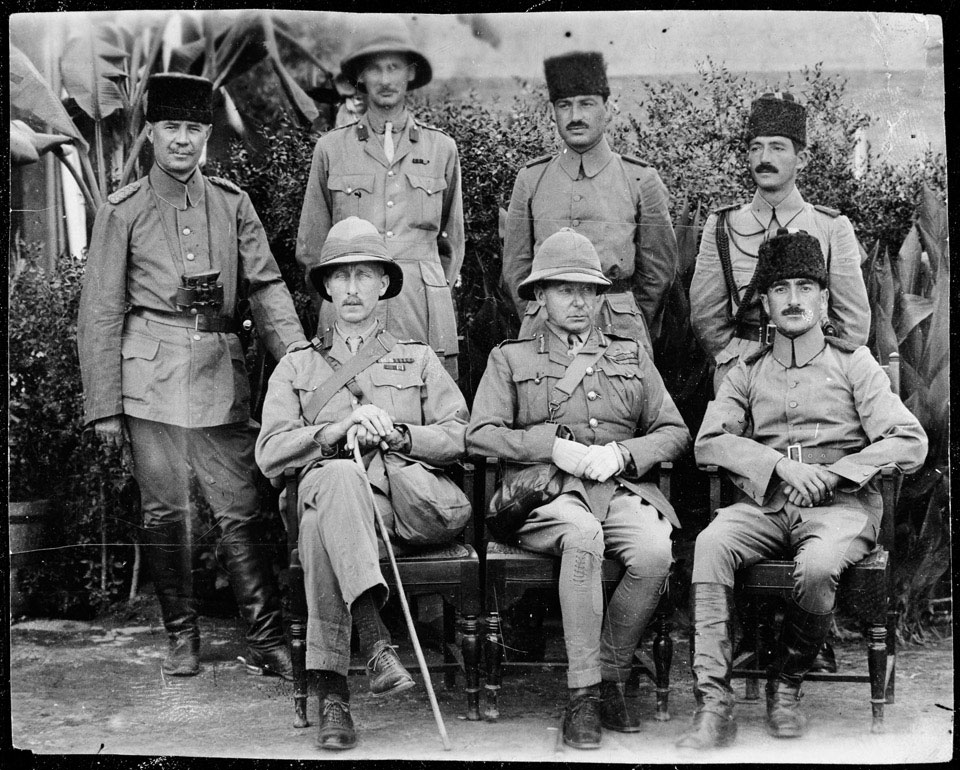

A single division was not strong enough for such an operation. Sickness and a lack of artillery, ammunition and supplies had seriously weakened Townsend's force. Even if he had been able to capture Baghdad, he did not have the necessary resources to retain it. On 21-23 November 1915, Townshend was blocked by the Turks at Ctesiphon. Suffering heavy losses, he decided to retreat back to Kut. (Townsend is pictured centre as a prisoner of the Ottomans.)

On 7 December 1915, the Turks surrounded Townshend’s 10,000 troops and 3,500 camp followers. For the next few weeks, they launched attacks against the Kut defences. Along with the regular shelling, this took a steady toll on the garrison, which only had food and supplies to last two and a half months. The defenders slowly starved. In early January, two Indian divisions, known as the Tigris Corps, were despatched under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Fenton Aylmer to relieve Townshend’s beleaguered forces.

Tigris Corps’ 19,000 troops fought their first major action at Shaik Saad, where 22,000 Turks had set up defences astride the River Tigris. Major-General Sir George Younghusband’s 7th Division attacked on both sides of the river – the 35th Brigade on the left bank, the 28th on the right – with a flotilla of gunboats and supply vessels in support.

The assault began at dawn on 6 January 1916. Lacking any elevated ground, effective aerial reconnaissance or enough cavalry, the attacking troops had to feel their way through mist to discover where enemy positions started or ended. Trying to manage the battle on both sides of the river, Younghusband was unable to control his forces properly. His attack failed with heavy losses on both banks.

Aylmer arrived with reinforcements, so another attack was launched the next day. But this too was beaten off. Attacking again during the night of 8-9 January, the British were then surprised to discover the Turkish trenches unoccupied. In fact, the Turks had withdrawn overnight, perhaps overestimating British strength. Aylmer pushed on and rapidly reached Hanna, about 16km (10 miles) from Kut. However, he was unable to break through during the Battle of the Wadi and the Battle of Hanna between 13 and 21 January 1916. Further attacks by the relief force in March and April all failed with heavy losses. In attempting to rescue the men at Kut, the relieving force suffered around 23,000 casualties.

By the end of April 1916, the Kut garrison was starving and sickness was rife. With no prospect of relief, Townshend was ordered to begin negotiations with the Turks. At the same time, the garrison started to destroy its ammunition and equipment. On 29 April, the garrison surrendered and 13,000 men marched into captivity. A third would die from disease, malnutrition and cruel treatment. The episode was one of the British Empire’s worst defeats of the war.

Tigris Corps retreated to Basra, where the British spent the remainder of the year rebuilding their forces. The extreme heat in Mesopotamia - alongside poor medical facilities, lack of clean water, flies, mosquitoes and vermin - led to appalling levels of sickness and death from disease. Despite the best efforts of medical staff, thousands of soldiers died, especially in the early part of the campaign.

Medical arrangements for the Kut relief forces were completely inadequate, made worse by rain and mud. Provision had been made to handle 250 casualties. By 9 January 1916, there were 4,000 in Tigris Corps. Many wounded had to wait 10 days before they were assessed at field ambulances and sent to hospitals at Basra. The British Government now took over control of the campaign from the Indian General Staff. In July 1916, it placed Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Maude in charge. Unlike his predecessors, Maude was a methodical leader whose force was boosted by increased artillery and improved logistical, medical and transport support.

On 13 December 1916, Maude began a second advance up both banks of the Tigris with an Anglo-Indian force of 150,000 men. At first, he made slow progress. An attack on the Khadairi Bend, a fortified river loop, which started in early January 1917, was held up. But by early February, British troops had begun to close in on Kut. They secured the river bank to the south of Kut. But the advance on the north bank of the Tigris was delayed downriver at Sanniyat. Maude decided to cross the river at the Shumran Bend, upstream of Kut, to cut off Turkish communications with Baghdad and besiege the town. In turn, this would force the enemy to abandon Sanniyat, and allow the force on the north bank to continue its advance.

The amphibious attack at Shumran began on 23 February 1917. It was spearheaded by 37th Indian Brigade. They overcame the defenders and pushed them back far enough to allow construction of a pontoon bridge to move men and supplies across the river. By nightfall, two divisions were across the river and pushing on to Kut.

A diversionary attack downstream at Sanniyat also managed to break through, increasing the pressure on the Ottoman defenders. They abandoned Kut the following day and began retreating towards Baghdad, pursued by Royal Navy gun boats. On 4 March 1917, Maude reached the defences on the Diyala River, just south of Baghdad. Here, he deployed his men so skilfully that the Turks were forced to abandon their lines without a major fight. On 11 March, British forces marched into the city.

However, lessons were being learnt. Between July and September Ramadi was attacked. The RFC provided maps. Water supply was prioritised. Lorries were used in lieu of horses which could consume up to 10 gallons each per day. Troops were allocated water supplies and the town was captured after a desert march.

The Turks withdrew north and established their headquarters at Mosul. The British resumed their offensive in late February 1918, but this petered out in April after they had to divert troops to Palestine to support the operations there. As armistice negotiations began, the British attempted to strengthen their bargaining position by renewing their advance. They defeated the Turkish 6th Army at the Battle of Sharqat (23-30 October 1918) a week before the signing of the Armistice of Mudros, which ended the war. Unfortunately, Maude died of cholera a week after the European armistice.

Although the Armistice said both sides were supposed to retain their current positions, the British pushed on to secure oil-rich Mosul on 14 November 1918. The campaign had finally been won, but at great cost. With over 200,000 British Empire troops committed against far fewer Turks, the whole deployment was arguably a drain on British resources that could have been used on other fronts.

The British suffered over 85,000 battle casualties in Mesopotamia. Many more men were hospitalised for non-battle causes, like sickness. Nearly 17,000 men died from disease. Despite Maude’s claims of liberation, the Army remained in the region. The new state of Iraq became a British mandate against the wishes of its inhabitants. In 1920, a major revolt broke out in the country, which the British eventually suppressed.

A well-presented and detailed account of a much neglected area of study.

Terry

Book "British Prisoners of War in WW1 Germany"

Over 185,000 British military servicemen were captured by the Germans during the WW1 and incarcerated as prisoners of war (POWs). In this original investigation into their experiences of captivity, Wilkinson uses official and private British source material to explore how these servicemen were challenged by, and responded to, their wartime fate. Examining the psychological anguish associated with captivity, and physical trials, such as the controlling camp spaces; harsh routines and regimes; the lack of material necessities; and, for many, forced labour demands, he asks if, how and with what effects British POWs were able to respond to such challenges. The culmination of this research reveals a range of coping strategies embracing resistance; leadership and organisation; networks of support; and links with ‘home worlds’. British Prisoners of War in WW1 Germany offers an original insight into soldier captivity, the German POW camps, and the mentalities and perceptions of the British servicemen held within. Oliver Wilkinson, University of Wolverhampton

Review: ‘In this meticulously researched book, Oliver Wilkinson tells us why military captivity in the First World War mattered. Significantly, he demonstrates that POW camps were not a separate universe, divorced from fighting front and home front, but intimately connected with both. This is a story told with passion, but also with scholarly precision and close attention to detail.’ Matthew Stibbe, Sheffield Hallam University

1919 Peace Day March in London

On 30 June 2019, high above Hyde, on Werneth Low (240m) a small crowd gathered at the war memorial there to commemorate the centenary of Peace Day, the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28th June 1919. They marked it with a small service which the Rev. Jeremy Bentliff of St. George’s led, with music from the Hattersley Brass Band.

The location of the war memorial was quite apposite as the view to all of Hyde can be seen easily and conversely the memorial at the Cenotaph there is visible from most of the town. The borough lost 710 men and amongst those buried in the local cemetery is Harry Whittaker, aged just fifteen, one of the youngest to enlist. “My Country Needs Me”, a short poem composed by Aimey Saxon and Evie Thompson, was read as part of the service. Wreaths were laid, then the Last Post followed by the exhortation. A century ago on 19th July men from Hyde had a procession and sang war-time melodies including “It’s a long way to Tipperary”, the song supposedly written in Staybridge for a bet, was part of the act of remembrance here too.

The Hyde War Memorial Trust has a constitution that states two annual events must be held, Remembrance Day and Peace Day. A century on Hyde remembered the signing of the Treaty on 28th June 1919 on a wind-swept hill, a far cry from the ‘Hall of Mirrors’.

Neil Shuttleworth

Memorial at Werneth Low

12th Manchesters Remembered: Contalmaison July 2008

On the morning of July 7, 1916, the men, and boys, of the 12th Manchesters stepped out of their trench in sunlight and headed across open ground towards the German guns. By the end of the morning sixteen officers and 539 men would be dead, missing or wounded. This from an initial roll call of around seven hundred.

Like so many others before and to follow, the bodies of many of the dead were never recovered from the battlefield and they are commemorated by name only on the Thiepval Memorial to the missing of the Somme. In the small village of Contalmaison, the presence of two military cemeteries tell their own story, while a Croix De Guerre attached to a deceptively weathered building shows that this village was reduced to rubble in the 1914-1918 war. There are only third-hand memories left in the village of those turbulent times.

The carnage of July 7, 1916, had resulted in an oak cross being unveiled by survivors of the 12th Manchester battalion in 1927. This was replaced two years later with a granite monument in the public cemetery. However, after battlefield tour guides pointed out that few people were aware of its existence, the Lancashire and Cheshire branch of the WFA decided that something should be done. An appeal was launched to provide road marker signs and a smaller ‘sister’ monument that explained, in English and French, what had happened on the site of the memorials.

In July 2008 a coach party from Manchester travelled to the village for a ‘rededication’ ceremony at the existing monument and the unveiling of its newly-completed companion.

Led by the Somme Battlefield Pipe Band, a platoon of the Khaki Chums living history group in WWI infantry uniforms – badged 12th Battalion Manchesters, a colour party from the 1914-18 Manchester Regiment, standard bearers made up of veterans from the Second World War and officers of the 75th Royal Engineers of Failsworth, a large crowd paraded to the communal cemetery for the rededication and unveiling ceremony.

The two memorials, at the rear of the plot, sit proudly on part of the old German trench system that the 12th Manchesters had as their objective.

Then Mayor of Contalmaison, Madame Patricia Leroy, ex-Branch Chairman, John Richardson and Clive Harris, spoke poignantly of the sacrifices of a previous generation before a lone piper played a mournful lament. John Richardson said “I feel that we have finally paid due respect and thank the people of Greater Manchester, and members of the WFA, for their donations to help make this possible. The new memorial was important. It not only marks the events of July 7, 1916, but pays tribute to all of the men from the battalion who went on to give their lives in the Great War – more than 1,000 of them.

The ceremony was very moving, but it will soon be forgotten. What is important is that in 60 years - and maybe 600 years – this memorial will still be here to tell future generations what happened to men from their own local communities.” Martin Purdy

Photo of John Richardson, Martin Purdy and Tom Willis are flanked by two captains representing the 75th Royal Engineers who delivered the new memorial to its destination

UK’s biggest second and first world war prisoner camp unearthed in Yorkshire

The forgotten history of what was once Britain’s biggest prisoner of war camp has been unearthed by archaeologists in the Yorkshire countryside.

At its peak in the second world war, Lodge Moor camp near Sheffield held more than 11,000 mostly German captives.

Its extraordinary stories have been overlooked for more than 60 years as its moss-covered remains were shrouded in thick woodland.

Research by archaeology students shows the camp was used to hold the most fanatical of prisoners during the second world war, many of whom were from Germany, Italy and the Ukraine.

Analysing camp records, witness statements and surveying the prison’s weathered remains for the first time, the University of Sheffield students found the camp held more than 11,000 people at its peak in 1944.

But it was during the first world war that the prison, formally known as Prisoner of War Camp 17, held its most infamous inmate. Admiral Karl Dönitz was the captain of several German U-boats who was captured by Allied forces when his vessel, U-boat 68, was forced to surface in October 1918.

The admiral spent about six weeks at the Sheffield camp, according to the research, before feigning mental illness to avoid being treated as a war criminal. Dönitz was released back to Germany, where he rose to become commander of Hitler’s U-boats and head of the German navy, before going on to succeed Hitler as president of the German Reich.

Lodge Moor was one of about 1,500 prisoner of war camps in Britain during the second world war but its significance, in terms of its huge size and type of prisoner, was not widely known.

In common with other prisoner of war camps in Britain, Lodge Moor saw its share of drama. On 20 December 1944 a group of German prisoners managed to escape the site – but were captured in nearby Rotherham just 24 hours later.

Another escape plan ended in grisly fashion. One prisoner, Gerhardt Rettig, was chased around the Nissen huts by hundreds of inmates and beaten to a pulp after being suspected of tipping off Allied guards about a planned break-out in March 1945. Rettig later died in prison and his alleged killers were put on trial in London later that year. Two men, Armin Keuhne, 18, and Emil Schmittendorf, 31, were found guilty of his murder and executed by hanging at Pentonville prison in November 1945. The Guardian