Last Month’s Talk

Greg Baughen presented an excellent and well sourced talk on how the Royal Flying Corps set about tackling the enemy air force

Long before the first shots were fired in the Great War, army generals knew that aircraft were going to play a crucial role in future wars. They also realised that some way of shooting down enemy planes had to be found. Designers and engineers were soon struggling to find a way of doing this.

Inspired by the Royal Navy's dreadnoughts, the Royal Flying Corps planned to rule the skies with their own aerial battleships. It was an approach that proved to be a mistake and would delay the development of the single-seater fighters that were needed to challenge the German Fokkers and Albatrosses. The Pup, Camel and S.E.5a eventually emerged and helped save the day, but the battleship fighter was never abandoned completely. Even at the end of the war, there were still plans to develop them and the concept would continue to influence British fighter design long after the First World War.

The talk also considered the technical problems that affected the design and stability of the aircraft. Reflecting the idea of an aerial gunship, the designers tried to create an aerial equivalent of a naval gunship. The problems of recoil from firing a cannon where all too obvious, and although ‘pushers enabled a gunner to be placed at the front of an aircraft it was not a satisfactory solution. A number of specialist gun ships were considered but all were far too cumbersome to be of use

To contest the skies with the enemy, a scout (fighter) would be limited by weight restricting designs to a single engine. The contemporary designs were extremely lightweight and could not support heavy ordnance. Lewis guns could be attached to the upper wing, but required the pilot to stand when firing. The ideal was to be able to straight ahead. The only problem was the propeller.

The French pilot Roland Garros experimented with deflector plates on the propeller that caused the bullet to shoot away at an angle when it hit the propeller. On 1st April 1915 Garros achieved his first success with this modification.

Garros was forced to land soon afterwards and the Germans captured his aircraft. They employed the Dutchman Fokker to consider this problem and he eventually came up with an interrupter gear that stopped the machine gun from firing when it was in line with the propeller. This proved a great success and gave the enemy the upper hand until the Allies were able to develop their own.

An excellent detailed talk that included some remarkable photographs of experimental gunships and the like. Ed

100 Years Ago

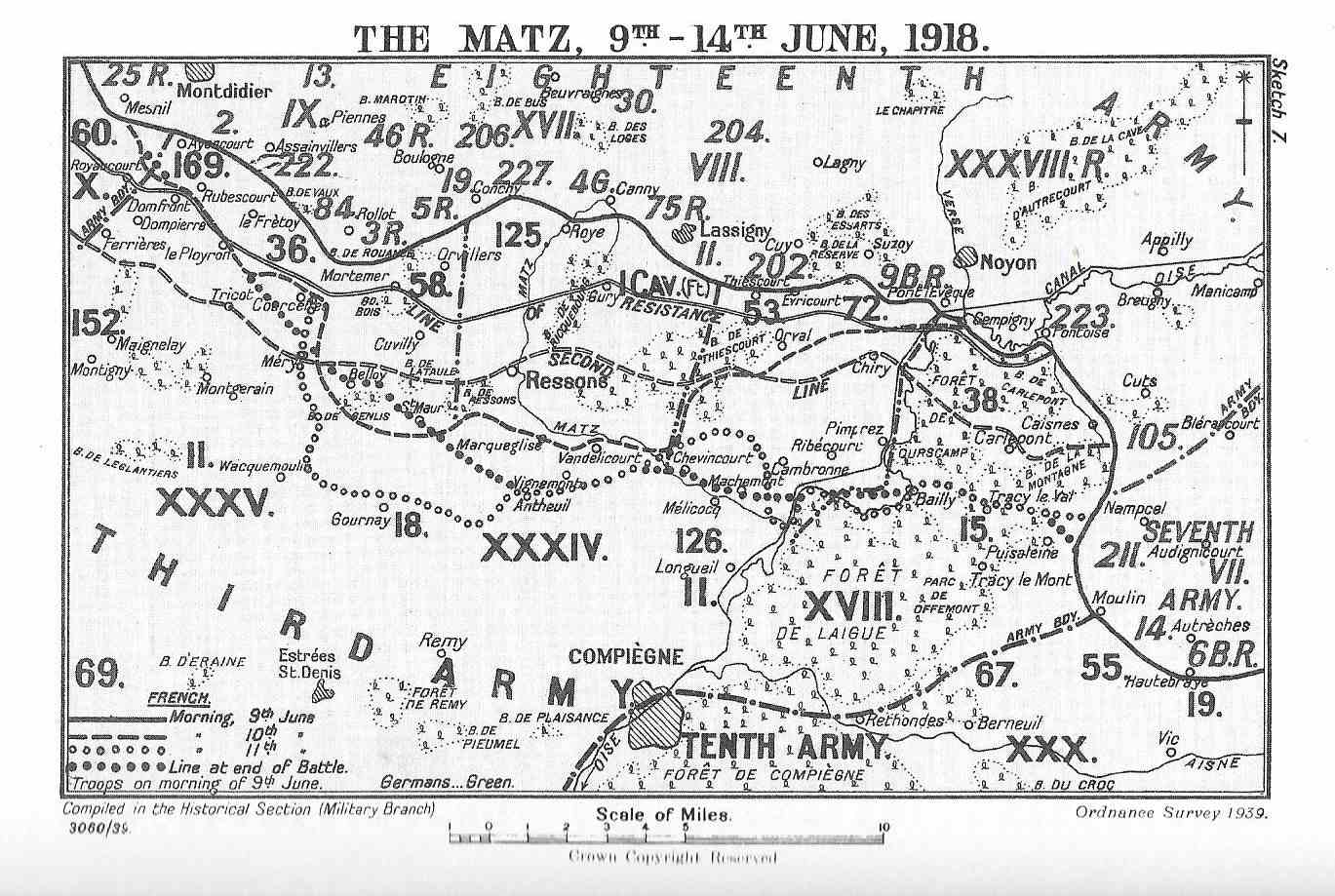

The Third Battle of the Aisne (Blücher-Yorck) had petered out on 6th June 1918. Victory seemed near for the Germans, who had captured just over 50,000 Allied soldiers and over 800 guns by 30 May 1918. But advancing within 56 kilometres (35 miles) of Paris on 3rd June, the German armies were beset by numerous problems, including supply shortages, fatigue, lack of reserves and many casualties.

Although Ludendorff had intended Blücher-Yorck to be a prelude to a decisive offensive (Hagen) to defeat the British forces further north, he made the error of reinforcing merely tactical success by moving reserves from Flanders to the Aisne, whereas Foch and Haig did not overcommit reserves to the Aisne. Ludendorff sought to extend Blücher-Yorck westward with Operation Gneisenau, intending to draw yet more Allied reserves south, widen the German salient and link with the German salient at Amiens.

The French had been warned of this attack (the Battle of the Matz) by information from German prisoners, and their defence in depth reduced the impact of the artillery bombardment on 9th June. Nonetheless, the German advance (consisting of 21 divisions attacking over a 23 mi (37 km) front) along the Matz River was impressive. It resulted in an advance of 9 miles (14 km) despite fierce French and American resistance. At Compiègne, a sudden French counter-attack on 11th June, by four divisions and 150 tanks (under General Charles Mangin) with no preliminary bombardment, caught the Germans by surprise and halted their advance. Gneisenau was called off the following day. Losses were approximately 35,000 Allied and 30,000 German.

Although the Germans tried one last offensive Friedensturm in mid-July, their force was spent and the Allies would be soon ready to launch their ultimate attack in early August, leading to the ‘100 days’ during which the Germans realised the game was up and ultimately sued for peace in early November

Ed.