Chairman’s Notes

Good evening and welcome to the November meeting. As usual we shall be holding a short ceremony in the Drill Hall before the meeting to reflect the forthcoming Remembrance weekend. We must also thank our friends from the Sea Cadets for their playing of the Last Post.

I shall be representing the WFA on Remembrance Sunday at the local service in St Georges, New Mills and will be laying a wreath. It is more relevant this year as 6th Battalion Cheshire Regiment suffered heavy casualties on the opening day of Third Ypres.

I also intend to lay a wreath at the Menin Gate on 18th December, with the added fact that that day will be my 70th birthday.

I am pleased to welcome back Mike Stedman to the Branch. I am sure we will be fully entertained by his account of the attack at Thiepval on 1st July 1916. It saw some of the heaviest fighting on that historical day.

Next month we will be having our annual hot pot supper after the talk to be given by Mike O’Brien.

Terry Jackson, Chairman

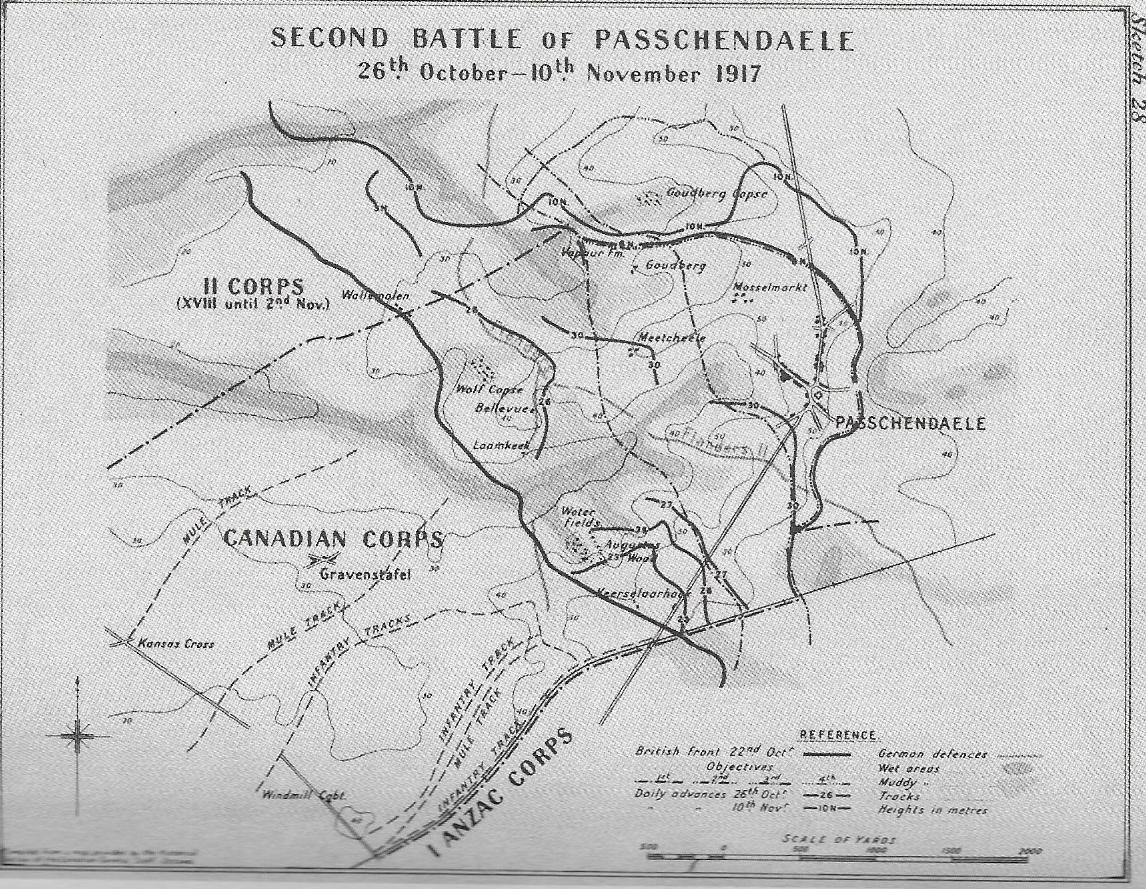

100 Years ago 10th November 1917

On this day, the last major assault in the Third Battle of Ypres was made. The Canadians had made a successful assault on 6th November against Passchendaele, with flanking protection by I Anzacs Corps to the right and II Corps to the left. The weather was fine but cold with later occasional showers. The attack started at 06.00.

Improved techniques such as the silencing of pill boxes by Lewis guns and grenades enabled the Canadians to stream through the village exacting a heavy toll of the enemy with the bayonet. A ’splendid’ barrage enabled the eastern crest beyond the village to be taken. The garrison at Mosselmarkt was surrounded and over 50 of the enemy were captured.

At 09.30 enemy reinforcements tried to advance but were taken out by artillery fire. Despite increased enemy artillery shelling, the Canadians used shell holes as protection and suffered few casualties.

Preparations were then begun for further advance, during which General Plumer handed Second Army command to Rawlinson as the former left to command British forces in Italy.

On 10th November the 1st Canadian Division pushed a further 500 yards northwards with flank protection by British 1st Division and elements of the Canadian 2nd Division. Despite the enemy concentrating its artillery on this narrow frontage the Canadians resisted, repulsed a counter attack consolidated a system of outposts which did not offer a good target.. VIII Corps subsequently took this over. The rain began to fall. Unfortunately the 1st South Wales Borderers allowed a gap to develop on the right, enabling the enemy to exploit it.at the expense of the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers who suffered 384 casualties. Subsequently 1st SWB had to retreat to their starting position.

The relative success of this action was reflected in good staff work and training in the Canadian Corps. This had previously been manifested at Vimy and Hill 70 earlier in the year.

The intention to capture the main ridge northwards was thwarted by the intervention of Lloyd George and his cabal. The loss of units and Plumer to Italy removed any chance of further progression and also weakened the plan for Cambrai. The four divisions of Fourth Army were politically allocated to take over forty miles of French units frontage south of the Somme.

It would be these units that would feel the full force of the March Offensive in 1918.

From Official History 1917 Vol II

A further attack at night was made on 2 December. This will form the topic for one of our speakers next year. Ed

Last Month’s Talk

The role of nurses in the Great War has always featured in its historiography and Dr Phylomena Badsey provided the Branch with details of its organisation and persons involved.

The men of the BEF were always under medical supervision. When a soldier was wounded the nursing profession were tasked with the aim of treating the wounded and where possible returning them to their units to carry on the fight.

Dame Maude McCarthy was the Principal Matron in France and Flanders and served throughout the conflict. She was born in Sydney and took up nursing when in London. Following her experiences in South Africa, she eventually took up her role at the very outbreak of the war in 1914. She served for the whole of the conflict and was to oversee a vast expansion of medical facilities. Her nursing staff expanded from 516 in 1914 to over 6000 by the end of the war.

Katherine Furse became head of the Red Cross VAD nurses in France. Her success brought her back to London to be its head. In 1917, being frustrated by the lack of control over her units, she accepted the position of head of the Women’s Royal Naval Service.

Nurses were often within the range of enemy action, especially by aerial attack. The hospital at Étaples was bombed and nursing staff were killed. However, the town housed many able bodied soldiers undergoing training. It also had excellent rail links and it could be expected to be vulnerable to this new form of warfare.

Hospital ships were also subject to enemy attack mainly by submarines. In a number of cases the enemy justified their actions by claiming the ships were also carrying arms or soldiers on their outbound voyages.

Nursing was a major link in the chain of treatment of casualties. At the front, drafted civilian doctors worked in Regimental Aid Posts as the first point of treatment. First aid and basic first aid was given. More serious cases would then begin a trip up the chain of care. Ultimately hospital ships and ambulance trains could move substantial numbers. The latter were vital in evacuating the sudden surge of casualties at the start of a major battle.

The aim of nursing was to give the patient early and continued treatment. Whilst the ‘Golden Hour’ thesis may be exaggerated as a universal thesis, in combat many wounded soldiers will undoubtedly benefit from early treatment. As the war progressed better method were developed to help wounded men. Some complaints were not specifically related to combat-trench feet and venereal diseases did not specifically come from combat.

Treatment and duties of nursing staff were varied. Once a casualty was stabilised nurses would have to ensure treatment continued. Initially soiled clothing had to be moved. Each patient had his own recovery programme. Some wounds such as gas infection, were more difficult to treat than others. Nurses in the major hospitals could be very busy. Sometimes one nurse might be responsible for the welfare of up to 17 patients.

Nursing practice varied with the terrain. Casualties at Gallipoli had to be treated on offshore hospital ships due to the narrowness of the allied frontline from the sea. In the more stable land campaigns a system of treat, return or move on developed. On land wounded men needing specific move back to a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). Here men be would stabilised and given treatment as necessary. If they were not able to be returned to their units they would be sent to a base hospital on the coast. CCS also became synonymous with war cemeteries as those badly injured failed to survive

Our thanks go to Dr Badsey for a detailed account of the nursing of casualties during the conflict. Ed

Photos: Dame Maud McCarthy

Katherine Furse (WRNS)