Chairman’s notes

Good evening and welcome to the March meeting. It is good to be back and I must thank Phil Hamer for ably stepping in during my absence. Also, thanks to Alex and Maureen for bringing the equipment to the venue.

Naturally, we regretted that we could not experience Peter Hart’s talk, which, from all accounts was top rate. Nevertheless, Ann and I had a wonderful time in Rome, Venice and Padua. In the latter, whilst Ann visited the famous Giotto chapel, I had a look at the old part of the town. There is a war memorial with a list of servicemen, but it appears to be for the later conflict.

I am pleased to welcome back Clive Harris to the Branch. Clive is an experienced Battlefield Guide and many of our members have benefited from his unsurpassed knowledge of the Great War whilst on his tours. I have been with him in the locality of tonight’s talk and I know you will be fully entertained and enlightened.

Terry Jackson, Chairman

Last month’s talk

Peter Hart explained in his own inimitable style why he considered the Battle of Jutland was so important in the outcome of the Great War. As a maritime power, Britain had concentrated on its navy, ensuring Britannia ruled the waves. This was unlike our traditional enemies, France and Russia, who had created large armies.

However, towards the end of the Nineteenth Century, Germany, ‘The New Kid on the Block’, began to flex its muscles. The Kaiser was convinced that any extension of his colonial ambitions depended upon the strength of his navy. In response Britain began the development of the heavily armoured Dreadnought Class Battleship. The first ship was launched in 1906. It had a main armament of ten 12” guns and was powered by the latest turbine engines. A new Battlecruiser Class was also produced. This had eight 10” guns and a top speed of 24 knots.

Germany took up the arms race, almost as a personal affront. It built ships with thicker armour, although this resulted in a slower speed. Britain responded with the Super-Dreadnought which had eight 15” guns and 13.5” armour plating. This created stalemate at the outbreak of war, with the German High Seas Fleet remaining in port at Wilhelmshaven.

Traditionally, in the days of sail, Britain mounted a naval blockade on its enemies. In the modern era it was not feasible to lay siege outside the enemy’s ports. The need to refuel and the threat of underwater mines persuaded Admiral Jellicoe to mount a distant blockade. This involved the mining of the Dover Straits and patrolling the North Sea between Scotland, Orkneys, Shetlands and Norway. Thus the entire North Sea became a contested area, with the British Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow and the Battle Cruiser fleet in the Firth of Forth.

Admiral Scheer tried to provoke Britain with early forays, including the bombardment of Scarborough, Whitby, Sunderland and Hartlepool on the east coast. However, the Germans thought there was too much at stake to risk a major attack.

On 30th May 1916, the British Intelligence Service in Room 40 of the Admiralty Building decrypted a German message, using codes retrieved by the Russians from an enemy ship. This alerted them to an impending incursion by the enemy High Seas Fleet on 31st May. The British set sail at 11pm, 30th May, in advance of the Germans sailing at 2.00am the next day.

Peter then gave a detailed analysis of the progress of the battle which resulted in the sinking of the Indefatigable at 4.02pm. The ship sank within ninety seconds of being hit, with the loss of over one thousand lives. This was followed by the sinking of the Queen Mary and Invincible with a combined loss of over two thousand sailors.

By 7.30pm visibility was becoming affected by smoke and failing light. The battle petered out and the German fleet regained its home ports. Neither side gained for what they had aimed. The enemy claimed a victory, which was true in terms of tonnage sunk and lives lost. But the British achieved a tactical success. The status quo and blockade remained, the latter depriving the enemy of food and materiel.

‘Although the Germans had assaulted their gaoler, they remained in prison’.

Thanks to Phil Hamer for this detailed report on Peter’s presentation. Ed

100 Years Ago

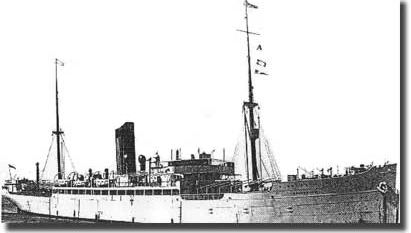

Losses in New Zealand shipping mounted alarmingly in 1917-18 when Germany stepped up its submarine warfare against Allied commerce. One action stood out, the epic 1917 battle between the Otaki and the German auxiliary cruiser Möewe (‘Seagull’).

Both were merchant ships, but there the similarity ended. The newly built 9800-ton Möewe carried four 150-mm guns, a 105-mm gun, two smaller pieces, torpedo tubes and mines. All were

concealed, for the ship operated disguised as a merchant ship. It carried a highly trained naval crew of 235 and was fitted with sophisticated radio gear. By contrast, the 7420-ton Otaki (built in 1907 - see photo right) had been given two Royal Navy gunners to man its stern 4.7-inch (120-mm) gun. This lone weapon could throw a shell less than half the weight of one from the Möewe’s guns. At heart, the Otaki remained a food carrier, crewed by 71 civilians.

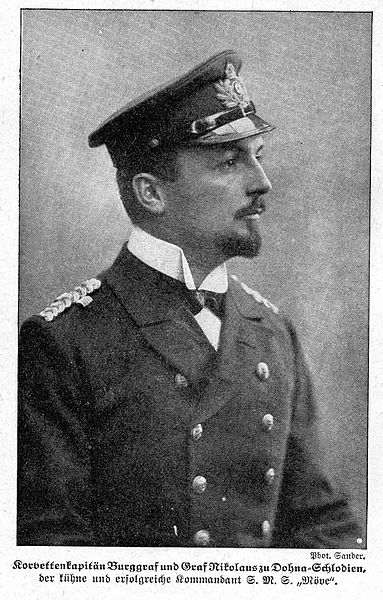

The Möewe’s commander was Korvettenkapitan Niklaus Graf und Burgraf du Donna-Schlodien. He had served in the Kaiser’s navy since 1896 and had been the navigator of a battleship prior to taking charge of the Möewe. The Otaki’s Scottish master, 39-year-old Captain Archibald Bissett-Smith, was about the same age and an equally experienced seaman, but in the Merchant Marine. The Möewe was a successful raider, sinking or capturing more than forty vessels in 1916-17

They crossed each other’s paths early in the afternoon of 10 March 1917 off the Azores in the North Atlantic. The Möewe had sunk a British freighter that morning and its officers went swiftly into action when they sighted another ship in murky conditions. Squalls and rising seas made pursuit difficult, but the Möewe had a slight speed advantage and closed the gap.

Even after the Möewe broke out its battle ensign and turned to clear its firing lines, Bissett-Smith refused to back down. Instead, his gunners sent a round sailing above the raider’s bridge. In the

gunnery exchange that followed, the Otaki did surprisingly well. But the British ship had no chance and sank stern-first a few hours later, still flying its colours and taking Bissett-Smith with it. Five of his crew were killed; the survivors were taken prisoner. The Möewe, though, was also on fire and in danger of sinking. Donna-Schlodien averted disaster by cutting holes in the ship’s side to flood a bunker fire. The Möewe (see photo right) spent two highly vulnerable days wallowing on the high seas before it was repaired sufficiently to resume its raids on Allied shipping.

Only after the war, when the Otaki survivors were released, did the full heroism of the incident emerge. In 1919, in a rare move, the King awarded Captain Bissett-Smith a posthumous Victoria Cross, the conditions for the award having been met by retrospectively giving him status as a temporary lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve. Several other crewmen were also given awards or Mentioned in Despatches.

Bissett-Smith and the Otaki subsequently entered the folklore of the Merchant Navy. In 1936 his family presented the Otaki Shield to his old school, Robert Gordon’s College in Aberdeen. It is awarded to the boy with the highest qualities of character, leadership and athletic ability. Two years later, to honour Bissett-Smith’s connection with New Zealand (as well as sailing for the New Zealand Company, he had married a Dunedin woman in 1914), the company added a travelling scholarship to the prize. The New Zealand government funded the Otaki Scholar’s stay in this country. Every year since then, apart from during the Second World War, the Otaki Scholar has visited New Zealand.

After the war the Möwe was taken to Britain under the Versailles Treaty and sailed as a merchantman. She eventually was returned to Germany and fittingly was sunk by Bristol Beaufighters of Coastal Command off Norway on 7 April 1945.

Ed.

Captain Bisset-Smith left, and

Captain Donna-Schlodien, right

Rome War Memorial

Whilst in Rome we visited the Vittorio Emanuele monument. This was completed in 1925. It dominates the central skyline and was not without its critics. (See photos below).

The monument holds the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier with an eternal flame, built under the statue of goddess Roma after World War I, following an idea of General Giulio Douhet. The body of the Unknown Soldier was chosen on 26 October 1921 from among 11 unknown remains by Maria Bergamas, a woman from Gradisca d'Isonzo whose only child was killed during World War I. Her son's body was never recovered. The selected unknown was transferred from Aquileia, where the ceremony with Madam Bergamas had taken place, to Rome and buried in a state funeral on 4 November 1921, before the final completion of the building. The dates (in Roman numerals) 1915-1918 are engraved in the frontpiece.

On the day of our visit it was flanked by two sailors, who had just completed a Changing of the Guard ceremony.

Ed.