Chairman’s notes

Good Evening and welcome to the first meeting of 2017. I trust that you have all had a good Christmas and New Year. We spent the former in Alicante and were fortunate to have a hotel overlooking the marina and sea. We also enjoyed excellent weather.

100 years ago the Allies were looking to force the Germans onto the back foot. The Somme had not provided the hoped for breakthrough for the Allies nor had the German offensive at Verdun been successful. The turn of the year was to see a change in leadership for both France and Germany. The Americans were beginning to arrive, but the plight of the Russians was increasing. Britain had a new Prime Minister who was to actively interfere in the workings of the military effort, often with severe results.

I am pleased to welcome back Taff Gillingham back to the Branch. Many of you will remember his talk on the personal equipment of the British soldier. I have a lasting picture of Taff proving how effective the pack was by completely inverting his colleague to show that even in this position the soldier would still remain securely bound to his webbing.

Taff, of course, is also an expert on the Western Front. During the Somme period last year, he appeared on several programmes. I was also pleased to meet him at the Suffolk Memorial, Le Cateau on 26th August 2014 at the 100th anniversary of that battle.

Taff will be analysing the ‘Christmas Truce’ of 1914, with particular emphasis on the ’International Football Match’. In a region where football still forms an important part of life with the two Manchester giants and numerous teams from professional to amateur level still active, the truce will be an interesting topic. Like much of the popular history of the war, a lot of added and unfounded details have been used to embellish the scene in the ‘Sun’ motto of ‘Never let the truth get in the way of a good story’. I am sure Taff will cut through the fog to reveal the true events.

Terry Jackson. Chairman

Last month’s talk

I was especially pleased to welcome John Hartley to the Branch. John had produced his work on Stockport Servicemen lost in the Great War, ‘More Than a Name’. The detailed records of these men have been essential in my research on Stockport Corporation employees who gave their lives.

John’s talk concentrated on the 17th Battalion Manchester Regiment, one of the Pals’ Battalions. Manchester had become the dominant world city during the cotton era. However, many of the early volunteers from the industrial cities had been workmen. An organised commercial and financial sector was essential to run the major industries in world trade.

By early September recruiting was ebbing and Kitchener targeted the middle classes. The North West was the home ground of Lord Derby, who was to implement an interim scheme of attestation before Conscription eventually came. Although the TAs did provide some of these men, many were unable to accommodate huge influxes, so Kitchener had decided to create a third strand behind them and the regulars. These became known as the Service Battalions.

As the war intensified the ‘pen pushers’ were in danger of being cast as avoiding the fray. However, their patriotism was as intense as their manual brothers and they too began to seek to serve the nation in the field.

Eventually after training the Battalion went overseas and their first casualty in the field was 2nd Lieutenant Robert Loudon Johnston. He was killed on 13 February 1915 after being struck by the casing ejected from a nearby artillery piece.

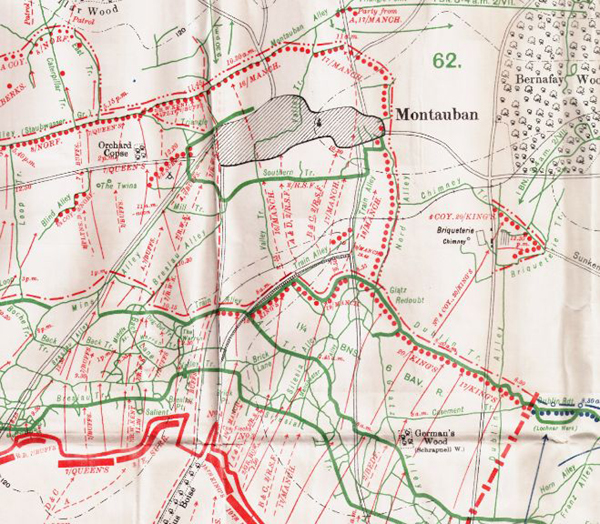

On 1 July 1916, 16,17&18th Manchester Regiment with 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers formed 90th Brigade of 30th Division (XIII Corps) at the southern extremity of the British line. The Division consisted of mainly New Army units from Manchester and Liverpool (Kings Regiment) plus four regular battalions.

The extreme right formed the junction with the French forces and with them the Liverpool units of 89th Brigade made a joint attack and captured Dublin Trench. The wire had been well cut, the French artillery having more experience and the overall aims not as demanding of those to the north of the Albert-Bapaume road. This prepared the way for the follow up by 90th Brigade. (16/17/18th Manchesters) and 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Despite casualties from an entrenched machine gun and the loss of all the commanders of the three Manchester units, a concerted effort was made. .A smoke barrage confused the enemy and the Manchesters entered the fortified village of Montauban. Seeing many of the enemy fleeing to Bazentin le Grand to the north, forward artillery observation officers directed fire on them. This also enabled the capture of La Briqueterie to the east, thereby removing the enemy observation post from its chimney. 20th Kings was then able to cut off Glatz Redoubt and capture the 62nd German Divisional colonel.

30th Division had been successful, clearing the Germans off a frontage of almost one mile and to a depth of 2000 yards. The next step would the advance and clearing of Bernafay Woods and beyond. For the whole of the BEF, the battle for the woods would involve some of the most vicious fighting of the whole battle.

An excellent in depth study of units from the catchment area of the Branch. Terry

100 Years Ago

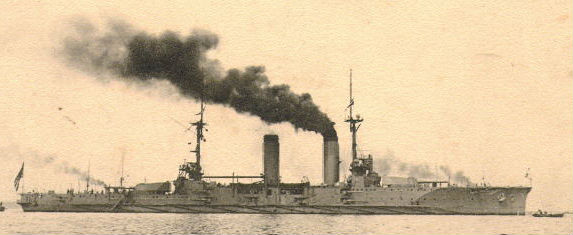

Construction of the Tsukuba-class cruisers was ordered under the June 1904 Emergency Fleet Replenishment Budget of the Russo-Japanese War. This was spurred on by the unexpected loss of the battleships Yashima and Hatsuse to naval mines in the early stages of the war. These were the first major capital ships to be designed and constructed entirely by Japan in a Japanese shipyard, albeit with imported weaponry and numerous components. However, Tsukuba was designed and completed in a very short time, and suffered from numerous technical and design problems, including strength of its hull, stability and mechanical failures. The ship was reclassified as a battlecruiser in 1912.

The Tsukuba-class design had a conventional armoured cruiser hull design, powered by two vertical triple-expansion steam engines, with twenty Miyabara boilers, yielding 20,500 shaft-hp, a design speed of 20.5 knots and a range of 5,000 nautical miles at 14 knots. During speed trials in Hiroshima Bay prior to commissioning, Tsukuba attained a top speed of 21.75 knots

In terms of armament, the Tsukuba-class was one of the most heavily armed cruisers of its time, with four 12-inch 41st Year Type guns as the main battery, mounted in twin gun turrets to the fore and aft, along the centerline of the vessel. Secondary armament consisted of twelve 6-inch (152 mm) guns and twelve 4.7-inch 41st Year Type guns, and four QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns.

Tsukuba was laid down on 14 January 1905, launched 26 December 1905 and commissioned on 14 January 1907 at Kure Naval Arsenal. Captain Takenouchi Heitaro was her chief equipping officer and first captain. Shortly after commissioning, and with Admiral Ijuin Gorō on board, Tsukuba was sent on a voyage to the United States to attend the Jamestown Exposition of 1907, the tri-centennial celebrations marking the founding of the Jamestown Colony. She then traveled on to Portsmouth, England and returned to Japan via the Indian Ocean, thus circumnavigating the globe.

After her return to Japan, Tsukuba was assigned to Captain Hirose Katsuhiko (the brother of the war hero Takeo Hirose) and escorted the United States Navy’s Great White Fleet through Japanese waters on its around-the-world voyage in October 1908. Captain Isamu Takeshita was captain of Tsukuba from July through September 1912, followed by Captain Kantarō Suzuki to May 1913, and Captain Kanji Kato from December 1913 to May 1914.

Tsukuba served in World War I, initially during the blockade of the German port of Tsingtao in China during the Battle of Tsingtao from September 1914, as part of Japan's contribution to the Allied war effort under the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. After the fall of the city, Tsukuba was sent out as part of the search for the German East Asiatic Squadron in the South Pacific until the destruction of the German squadron in the Battle of the Falklands in December 1914. Tsukuba remained in Japanese home waters in 1915 and 1916. On 4 December 1915, Tsukuba was in a fleet review off of Yokohama, attended by Emperor Taishō in which 124 ships participated. A similar fleet review was held again off Yokohama on 25 October 1916.

On 14 January 1917, Tsukuba exploded while in port at Yokosuka. Some 200 crewmen were killed immediately, and over 100 more were drowned as the cruiser sank in shallow waters within twenty minutes, with a total loss of 305 men. The force of the explosion broke windows in Kamakura, more than twelve kilometers away. At the time of the disaster, more than 400 crewmen were on shore leave, which is why so many survived. The cause of the explosion was later attributed to a fire in her ammunition magazine, possibility through spontaneous combustion from deterioration of the Shimose powder in her shells.

The masts, bridge and smokestacks of the vessel remained above water, and afterwards, her hulk was raised, and used as a target for naval aviation training. It was formally removed from the navy list on 1 September 1917 and broken up for scrap in 1918.