Chairman’s notes

Good Evening and welcome to the November meeting. As usual, there will be a small commemorative ceremony in the Drill Hall prior to welcoming our speaker. I am also greatly indebted to our friends from the Sea Cadets, for yet again, agreeing to provide the Last Post.

I am also pleased to confirm that after the December meeting we will be holding our annual hot pot-trench stew supper. Once again our in house chef, Simon Cooper will be in action.

I am pleased to welcome back Anne Pedley to the Branch. Her talk is on men in the mountains during the Great War and I am sure it will be an enjoyable and illuminating experience. Anne is the curator of the Royal Welch Fusiliers and also a regular speaker on the circuit. She is also a member of the North Wales WFA.

Last time Anne was here, I was able to take her on a tour of the memorials we visit on our Manchester City Centre tour. Despite terrible weather, including at one point a thunder storm. she found it most interesting.

I expect there will be a lull in media interest in the war over the winter. Of course, 1917 was a pivotal year in the War. The new French commander Nivelle was to promise certain victory, but unfortunately his plans failed. The subsequent French mutiny caused the BEF to have to take over more of the frontage, without being given the sufficient resources by the perfidious politicians at home.

Arras was to be the bloodiest British battle on the Western Front. Although it did not last as long as the Somme or Third Ypres, its daily casualty rate was much higher. Later in the year, Third Ypres was to bring the relations between the Military and Government to breaking point, despite a degree of success at Cambrai. Whilst the Americans finally decided to join the fray, the Russians were to collapse. Would we cope in 1918?

Terry Jackson, Chairman.

Last month’s talk

The Brigade formed an important role in the structure of the BEF, but its composition and function have rarely been understood by many. Rob Thompson set about explaining its role in the Great War.

The War was the first truly modern war based on the industrial system. The developed world had undergone a second industrialisation based on power such as electricity, gas and oil. Controlled organisation involved interdependency, management and administration. The ‘pen pusher’ though often derided, was necessary to ensure smooth and efficient running.

There are few publications on the Brigade. It is not as readily researched such as Battalions with their connections to local towns and villages, nor the Division which often embraced a defined area, such as the 18th (Eastern). Professor Peter Simkins regards the Brigade as the key component of the army structure and the main building block for attacks.

In 1914 the Division was the main self-contained fighting organisation. As well as fighting men and administrative staff, it comprised everything necessary to function independently including artillery to medical units, supply and transport. Its basic fighting unit was the one thousand strong Battalion. However, in order to progress a substantial attack, the Battalion was part of the Brigade structure. There were four Battalions to each Brigade and three Brigades to form the heart of the Division. (Later, due to losses, Battalions were reduced to three per Brigade).

The Brigade was the basic single tactical unit. It formed the major link between the higher levels of command- Army, Corps and Divisions- to the fighting units (Battalions) on the ground.

A Brigade was usually commanded by a Brigadier General. The principal working officers were the Brigade Major and the Staff Captain. The former was responsible for operations and interpreted the Corp Commander’s orders. He also identified the objectives and co-ordinated actions of the various units in the Brigade as well as liaising with other units where necessary. The Staff Captain was responsible for the every-day running of the Brigade including supplies, transport and discipline. This included looking after the smooth running of the trenches within which the soldiers had to occupy on a daily basis. Both these officers had subordinate ranks to act as Staff Officers as appropriate.

The Brigade controlled machine gun units and all aspects of trench life. The Staff Captain supervised the daily running of the unit. His remit included planning raids and the increased use of signals, bombs and gas. The mundane but vital organisation of transport, salvage, sanitation and pack (mules) expanded to oversee Chaplains, who increasingly stayed in the trenches and amusements for the men when not on duty.

In 1917 the Brigade was responsible for the wholesale movement forward to catch up with the Germans as they carried out their planned retreat to the Hindenburg Line. An important requirement was to ensure liaison with the French units on the British flank.

The Brigade role changed as the war developed. In 1914, the BEF was an old colonial force primarily fighting native uprisings. The Division and Battalion were the main units. The Brigade was virtually a post box between the two. There was little chance of promotion for the Brigade officers. However, as the BEF increasingly became an army in being. Huge numbers of men were involved and until an offensive answer was found, primarily it had a long term presence along an expansive frontage. The troops were engaged in the new field of warfare, whilst living in the trenches.

The Brigade increasingly took on more importance as it had to control the sharp end of the front line right back to the artillery lines and beyond. The Brigade began to take on more roles previously associated with Divisions. It was at the scene of the fighting and the fighting units were relating their experiences to Brigade Command. This was the increasing realisation that High Command had to learn from bottom up. It was the Corps and Army commanders who now had to interpret this information and co-ordinate it for application in the field. Divisions were now too far away from the front line fighting and beyond. They had also become one of many. As the BEF learnt from its fighting, Battalions ceased to be the main fighting unit. Smaller units such as Platoons fought more efficiently when equipped with a cross section of weaponry including Lewis Guns, Rifle Grenades and Bombs.

The Brigade was of the ideal size and in the right position to coordinate assaults. It developed its own Staff. It could see the Big Picture and organise troops which it knew. It oversaw new techniques, intelligence, technology and communications. It was a clearing house for collation of practice. It was also well positioned to deal with unrest in the front line by understanding its men. By the end of the war, the Corps had virtually taken over the Brigade’s role as a post-box as the latter fed more information direct to High Command.

As the war progressed the British developed the hand held bomb from a jam tin to purpose designed grenade. A bomb making school was developed and rifle grenades gave fighting units some effective artillery on the spot. Much of the work was done at Brigade level, from field experiences. Schools of instruction were set up and results sent to Division and beyond.

Between major assaults, it was the Brigade who organised trench raids. It was able to construct the size of unit involved across the individual battalions and co-ordinate intelligence. Brigade Staff worked long hours and officers suffered heavy casualties. Nearly 60 Brigadier Generals were killed on the Western Front, and more Brigade Majors and Staff Captains also suffered fatalities.

This was yet another fascinating insight by Rob into the complex nature of the role of organisation, logistics and officers in the field. It shatters the illusion of the comfortable Chateau Generals so loved by the press.

Terry

100 years ago

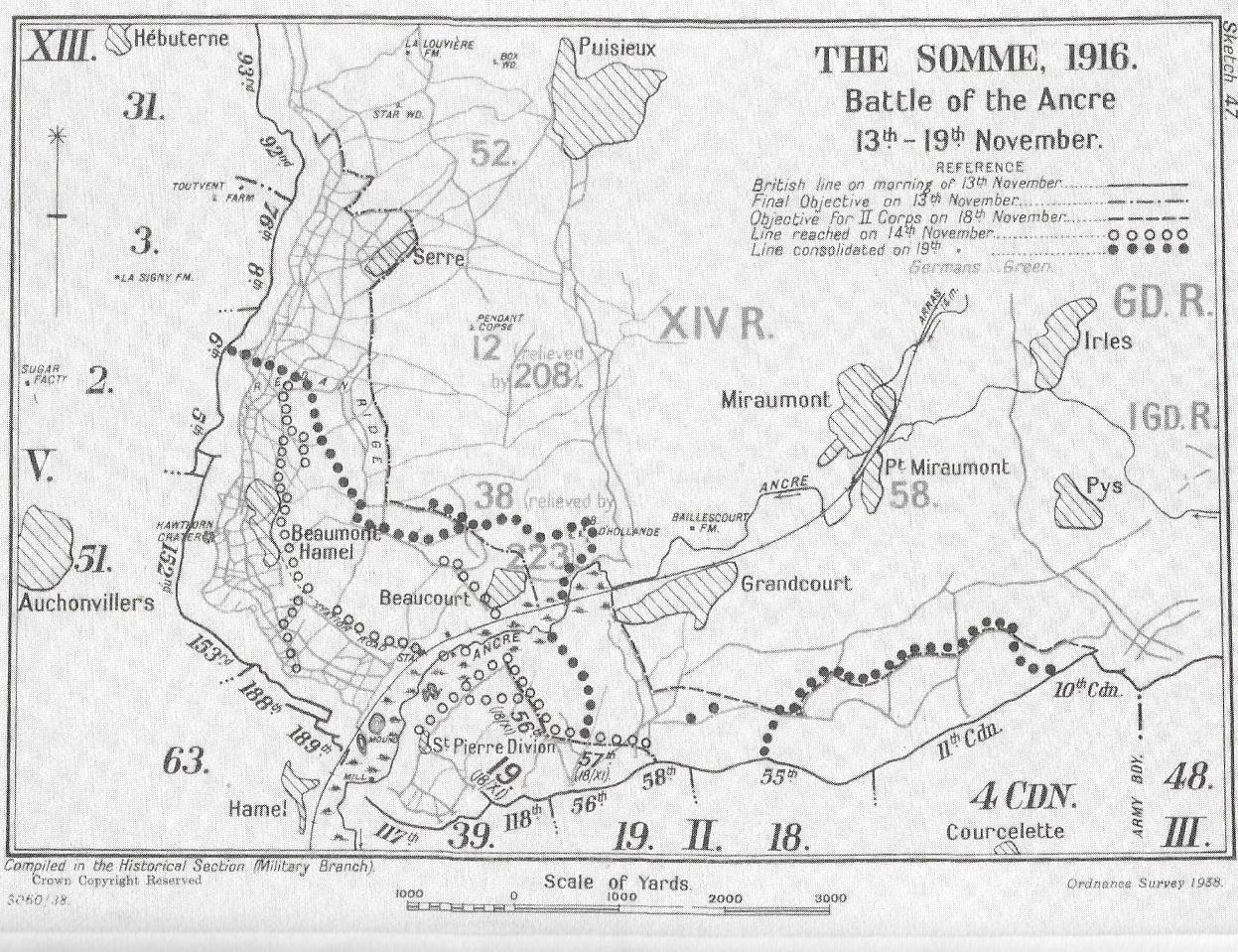

The 11th November was dull with much low cloud but no rain; little could be seen either from the air or from ground observation posts and heavy mist persisted upon the 12th. At 5am on this day No. 2 Special Company RE fired 180 lachrymatory bombs into Beaumont Hamel using 4” mortars. At 3.30pm, 47 gas drums were projected into the village and 39 into Y Ravine, causing the enemy, (62nd Regiment), as was found afterwards, considerable loss. Certain groups of tanks had moved forward from Beaussart, three miles behind the centre of V Corps front. However, on the evening of the 11th the officer commanding the tank company felt obliged to report next day that the bad state ground would prevent the machines from taking part. He was therefore directed to withdraw them at night. This was a difficult and fretful business to undertake whilst the troops were moving up. Therefore some tanks had to be left in their forward positions.

Most of the infantry had a long and trying march to the front, but the men’s sprit was remarkable considering they had spent weeks cold and often wet to the skin in muddy trenches. Billets and bivouacs were poor. As well as preparing for battle they had to scrape mud off the road.

The attack was constantly postponed but never cancelled, causing tension in all ranks. The relief came when they knew the attack was at hand. Movement to the front began in clear moonlight, the moon being above the horizon the early hours of the 13th. However, the battlefield had become shrouded in dripping fog. The enemy was unaware of their presence as the troops waited in close packed ranks until 5.45am. The barrage commenced and movement began. There was some confusion and in some places a loss of direction as visibility was barely 30yards. The Battle of the Ancre had begun. This was the last big British operation of the year and was the final formally notated assault of the Battle of the Somme. The Fifth (formerly Reserve) Army attacked into the Ancre valley to exploit German exhaustion after the Battle of the Ancre Heights and gain ground ready for a resumption of the offensive in 1917. Political calculation, concern for Allied morale and Joffre's pressure for a continuation of attacks in France to prevent German troop transfers to Russia and Italy also influenced Haig. The battle began with another mine being detonated beneath Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt.

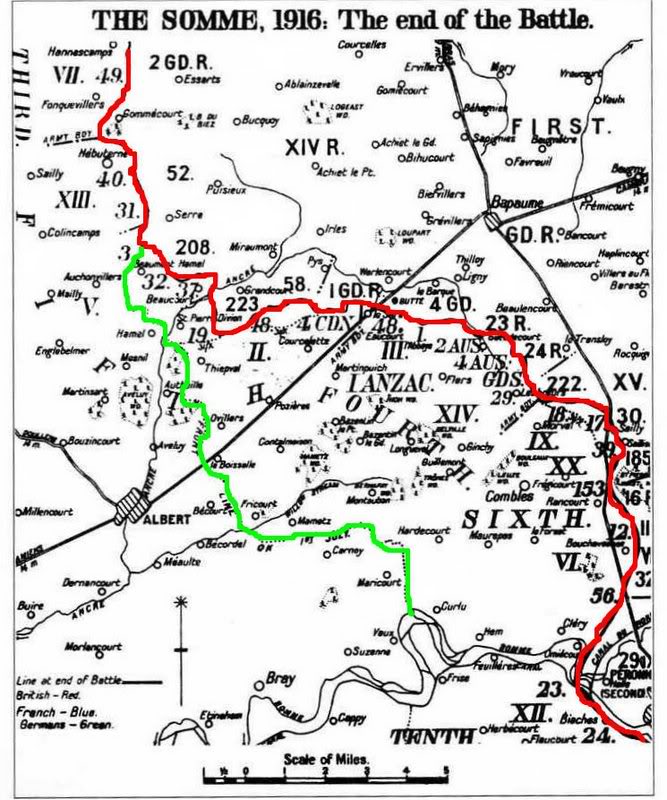

The attack on Serre failed, although a brigade of the 31st Division, which had attacked in the disaster of 1 July, took its objectives before being withdrawn later. South of Serre, Beaumont Hamel and Beauourt-sur-l’Ancre were captured. South of the Ancre, St. Pierre Division was captured, the outskirts of Grandcourt reached and the Canadian 4th Division captured Regina Trench north of Courcelette. They then took Desire Support Trench on 18 November. Until January 1917 a lull occurred, as both sides concentrated on enduring the weather.

Part of the above has been extracted from the Official History 1916, Volume 2.

The attached maps show the progress of the Battle of the Ancre (left) and the start and finish lines of the BEF on the Somme (right). These are represented in the latter by green and red lines respectively. Terry.