Chairman’s notes

Good Evening, welcome to the September meeting.

I am pleased to welcome Mike Coyle to the Branch. He will be explaining how memorials of the Great War can be compromised if not carefully monitored and will give us an insight to the problems that can beset the existence of these important markers of the conflict.

As a Branch we have on a number of occasions taken a walking tour round Manchester City Centre to look at some of those that are still there to remind us of this heritage. Also, you may recall that recently a new memorial to railwaymen was opened at Piccadilly Station. The fact that the original was lost in the original refurbishment in the seventies is a warning that memorials are often removed without warning and disappear often for ever. Terry

Last month’s talk

The prospect of a talk by Professor John Derry ensured a large audience. They were not to be disappointed. Professor Derry identified the three most important events of 1916. They were Verdun, the Somme and Jutland. He carefully analysed the effect of each.

Verdun lives on in French memory. It was a terrible battle that lasted from February to December. The estimated casualties were three hundred and seventy seven thousand French casualties and three hundred and thirty thousand German.

For Britain 1st July on the Somme is entrenched in British folk memory with fifty seven thousand casualties. Of these, over nineteen thousand were fatal. However, on 22nd August 1914, twenty seven thousand French were killed in the Battle of the Frontiers. Historically, the Napoleonic wars saw similar rates of attrition .However, unlike the modern industrialised war, actions rarely exceeded three days. The Somme spanned five months.

Jutland was the only major capital ships battle of the war. On 31st May the two fleets met with an inconclusive decision. Some historians have described Jutland as the unfinished battle. The merits of the actions of Jellicoe and Beaty have been the subject of much debate amongst historians.

The reason for the German attack at Verdun is not clear cut. Falkenhayn stated it was to bleed France white and force it to the conference table. Britain was Germany’s worst enemy, but in 1916 it had not developed a major army. By taking out France it removed Britain’s main sword. However, this aim was only made known after the war and there is no known evidence of his claim that he had informed the Kaiser of this.

It is unlikely France would have agreed to a cessation. Germany’s oppressive treatment of the occupied population was well known. (The treaty of Bret Litovsk was subsequently punitive). Verdun had been the last fortress to fall in the Franco-Prussian War and was therefore symbolic of French resistance. The citadel was a Vauban fort. A series of modern fortresses had been built beyond the Meuse to stem the advance of France’s traditional enemy on her eastern borders. However the Belgian fortresses had been taken and the French ones had been denuded of their main guns early in the war to boost its field artillery.

The two main forts of Douamont and Vaux were taken, but Pétain eventually stemmed the surge. He was critical of the French official doctrine of all-out attack, but was aware that artillery firepower ruled the battlefield. Pétain realised massing defensive troops in the front line was a recipe for disaster. Defence in depth was able to buffer the German attacks and they had made a fatal error of leaving the west bank of the Meuse initially untouched. This allowed the French to take retribution by their artillery situated there.

Petain also rotated the front line troops, unlike the Germans. This gave the whole French Army the sense of involvement in the national struggle, whereas the German units slogged it out without much relief. The French made a dedicated supply route to the city along La Vie Sacrée. The war became an attritional struggle, but eventually much of the taken ground and forts were recaptured. The symbolic nature of Verdun was obviously a stronger influence and inspiration on the French.

However there was to be a later knock on effect in 1917. George Nivelle commanded well and was able to convince the French politicians that his tactics at Verdun could be repeated and finish the war almost overnight. By 1917 British politicians had seen the losses of the British Army on the Somme. Lloyd George, by then Prime Minister, hated Haig and like Churchill was a committed ‘easterner’. They were convinced that knocking out Germany’s partners would undermine their ability to hold the Western Front against the combined French and British effort. Nivelle spoke our language perfectly, his mother being English. He was also a Protestant which immediately endeared him to the Welsh Wizard. Of course, Lloyd George had conveniently forgotten the Churchill sponsored disaster at Gallipoli. The Brussilov offensive in 1915, against the Austrians also promised the possibility of overstretching German commitments to her allies, but it had run its course by the end of the year.

The French offensive in April failed and brought about mutinies in the French army. Nivelle was replaced by Pétain. This was the beginning of the gradual take over as the prime army in the west by the BEF. However, it too was suffer. The Kitchener volunteer army was to have its baptism of fire prematurely in 1916 as a result of the degrading of the French Army at Verdun.

The Battle of the Somme was always going to be fought. It was planned when the BEF was still very much the junior partner. Politics always ensured that the British would have to fight alongside the French. Unfortunately, the two forces met just north of the Somme. The French therefore insisted that this was the place where a great joint assault in 1916 could push the enemy back. Unfortunately, Verdun removed much of the French forces from the scene, but they still called the tune. Haig would have preferred to have fought in Flanders, with realistic goals of reducing the Ypres salient, targeting the German submarine bases in northern Belgium, protecting the channel supply ports and threatening the German railhead at Roulers. The attack along the Albert-Bapaume road had little strategic merit.

To enhance the situation of the mainly untested volunteer units, a long bombardment was planned. Its aim was to obliterate the enemy in the front line, so the inexperienced volunteers could cross no man’s land. However, the calculation of the number of guns needed per yard of the attack was insufficient, being based on previous assaults on a smaller trench system. By 1916 the Germans had two main lines each of three rows of lines- lightly manned surface posts front line with deep dugouts, support lines behind with units waiting in deep shelters and a third line incorporating a rear shelter line for supplies and reserves.

The bombardment although lengthy was also poorly managed. Shrapnel was the main component, but this generally failed to cut the wire in front of the enemy trenches. High explosive shells buried themselves into the ground before exploding, creating craters, but generally having little positive effect. The whole artillery system needed improving. Scientific methods such as allowing for wind and temperature affecting the flight of the shell were ignored. Much of the ammunition was of poor quality with poor fuses and many were duds. The guns’ ranges were also affected by individual conditions. Guns set to a uniform range often fired long or short depending on the wear of the barrel.

Rawlinson advocated that the citizen army attacked in rows as they had not been fully trained. (Although some field commanders encouraged their men to adapt and get across the killing ground of no man’s land as quickly as possible)

The casualties on day one were of course high and have always been used to castigate a dim witted command chain. But this was not the real case. Tactics were revised and the artillery was improved. Artillery support for assaulting troops was vital and the benefit of the creeping barrage to supress rather than destroy enemy positions was realised. The whole artillery performance was enhanced. The introduction of the graze fuse meant that shells exploded on impact and not after burying themselves into the ground. Shells now exploded horizontally with maximum effect and without creating a moonscape of shell craters. The provision of sheer numbers of guns rained shells down on the suffering enemy. Air co-operation was improved, although air superiority would wax and wane over time.

Although the technology was primitive, the appearance of tanks in September would add a new dimension to assaults. The untried soldiers also became veterans and learned how to attack enemy posts. The need to protect the foot soldiers from enemy artillery also encouraged the development of counter battery tactics.

The Somme also had a negative on the German Army. Many of its best soldiers were lost and the continuation of the Verdun offensive stretched their human resources. The blockade was now beginning to bite. It had a serious effect on the morale on the front line troops as shortages now became critical, coupled with the bad news of its effect on the home front.

The Somme showed that the BEF could be persistent in its attack, giving Germany no respite. It added to the pressure to remove Falkenhayn. His successor, Ludendorff feared a resumption of fighting on the Somme, which he described at the muddy grave of the German Army. The assault on the Somme enabled the Blockade to effectively cripple the enemy. Germany had used much of its material and human resources in resisting the BEF. Previously their resources had been sufficient, but they would now suffer shortages in men and material at the front and in the homeland.

The Somme was vital in the decision of Germany to withdraw to the Hindenburg Line. Although it had a huge and formidable defensive system, Germany had to relinquish tracts of land in order to shorten their lines and man them with a depleted total of men. This had a double effect on future actions. Germany laid waste to the land during its retreat in order to hamper the allied follow up. However, it now had to try to hit their enemies, especially Britain by resorting again to unrestricted submarine warfare. However, this had the effect of bringing the USA into the war.

The threat of the eventual introduction of a large American army, backed by vast industrial resources, also caused the panic attack of the March 1918 German assault. Notwithstanding the additional manpower from the Eastern Front, it would never succeed and eventually only acerbated the problem. The Germans also were hoist by their own petard as they struggled over the land they had recently ransacked. A lack of strategical policy eventually wasted the resources of the German Army and set it up for a fatal repost beginning with the ‘Hundred Days’ assault at Amiens in August 1918.

The Battle of Jutland had a demoralising effect on the British public. It appeared that the world’s greatest navy had been given a bloody nose by a junior upstart. However, the material result in terms of tonnage sank did not ultimately prevent the Royal Navy from ruling the waves.

Germany’s admirals were faced with the conundrum of how to challenge the power of the Royal Navy. Germany’s High Seas Fleet was of good quality, but was always second in size to the British, which had a greater Dreadnought flotilla. Germany had some success in minor engagements, but the Kaiser’s fear of losing his precious navy kept it mainly in port, with a negative effect on its sailors’ morale. Scheer, who had succeeded Tirpitz, wanted an aggressive policy.

A German plan was devised to isolate part of the Grand Fleet so as to deny its numerical superiority, whilst the Royal Navy aimed to isolate Hipper’s Battle Fleet. In the initial encounter Beaty’s Battlecruiser Squadron was badly mauled by the Germans. British tactics had been based on rapidity of fire and safety precautions were ignored. Magazine doors were open for fast movement of shells and propellant cartridges were stored within turrets. The Royal Navy had become complacent but the enemy had endlessly practised gunnery procedure. This caused both Queen Mary and Indefatigable to be torn apart as enemy shells caused their main magazines to explode. Jellicoe subsequently twice crossed the T of the German fleet, but was unable to annihilate the enemy

In pure statistical terms of losses, those of the Royal Navy exceeded those of the Germans both in men and ships. However, the Royal Navy still commanded the seas and the German fleet having safely returned to base, never again seriously threatened British hegemony of the oceans. This caused Germany to resort to submarine warfare in order to try to starve Britain of essential foodstuff and materials and also relieve the effect of the blockade on its own imports. Unfortunately, their plan backfired. The sinking of unarmed ships, often carrying American civilians riled the USA. Whilst submarines initially sank much tonnage of vital supplies, the Royal Navy gradually learnt and adopted the convoy system. Eventually the isolationist America called time and declared war on Germany.

It was, therefore, Jutland that was the most important action of 1916. It forced the German Navy to stay in base. Ultimately as the tide turned, its sailors mutinied and undermined the political system. It was a major factor in bringing the world’s richest industrial nation to align with the Allies. The continuation of submarine attacks on neutral shipping was too much for America to tolerate. Although the US Army would take months to become effective, the writing was on the wall. It caused the Germans to waste the advantage of success in Russia, by the ill-conceived March offensive of 1918. This attack, although often spectacular, lacked strategic logic and ultimately failed. The blockade also caused anguish at home, which in turn was transmitted to the men at the front. This ultimately caused the German High command to force the Kaiser to abdicate and to accept Armistice terms in November 1918.

Yet another absorbing analysis of the War by Professor Derry.

Terry

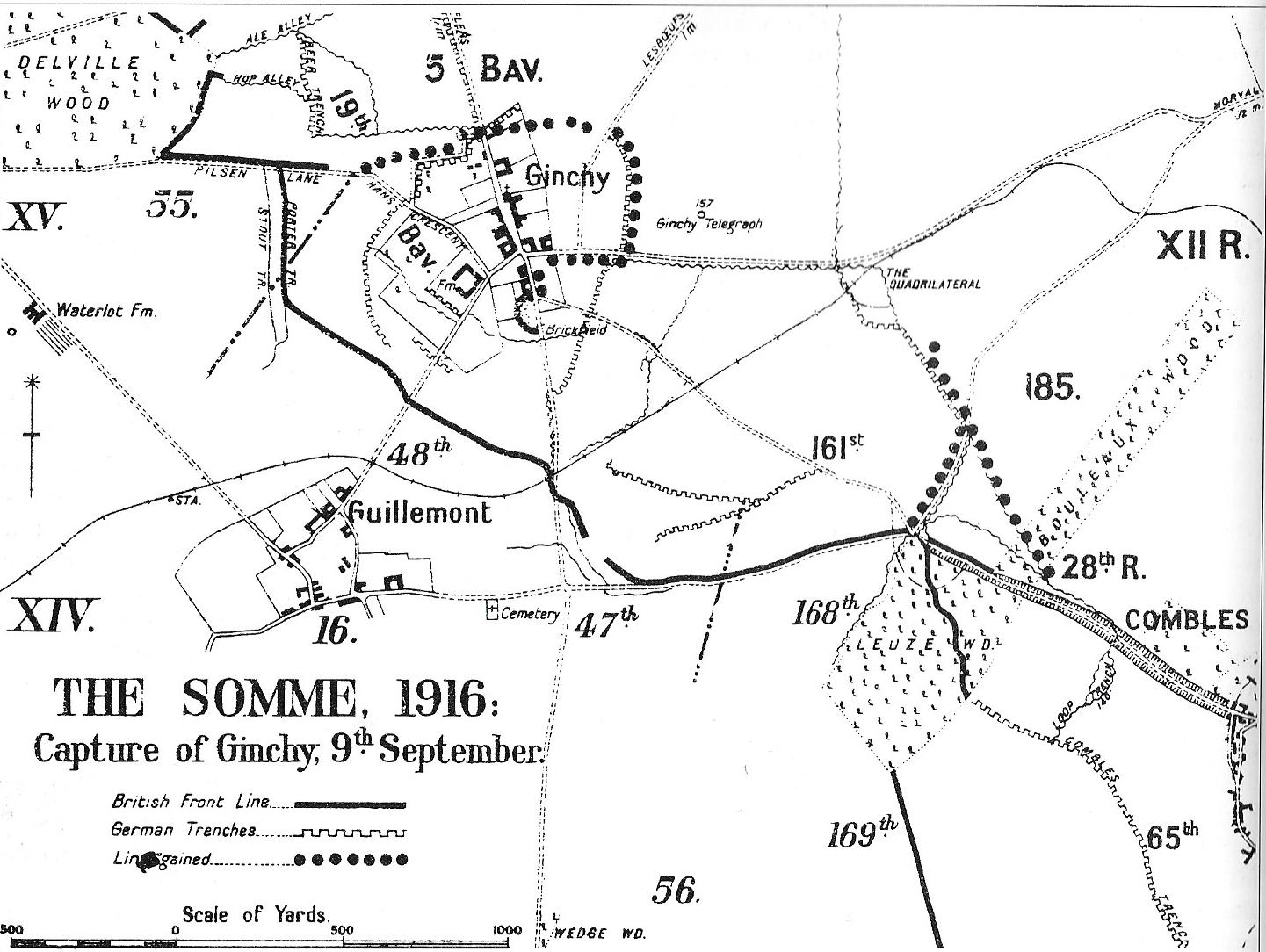

100 Years ago- the Capture of Ginchy

The Allied forces were continuing to push the enemy back and were fighting mainly to the south of the Albert-Bapaume road. XIV Corps had been pushing towards Guillemont and were to attempt to take Ginchy on the 9th September.

56th Division (168/169 Brigades) formed a defensive flank along Combles ravine, with the French on the other side. At 16.45 the London Rifle Brigade and part of 1/2Bn London Regiment (169 Brigade) advanced from Leuze Wood towards Loop Trench, but enemy fire repulsed them.

Meanwhile 1/9Bn London took the German main line in Bouleaux Wood up to the Morval Road.

168 Brigade was to push to the Leuze Wood-Quadrilateral Line.1/4Bn London (Royal Fusiliers) were successful and captured the trench south of the Quadrilateral, but 1/12Bn(Rangers) were held up by machine guns and only partly succeeded.

16th Division had trouble on the left. The Rangers lost their way so the London Scottish were called on to form the Brigades’ link. On the right 6Bn Royal Irish and 8Bn Royal Munster Fusiliers (47Bde) were held up so 48Bde wheeled right and routed the enemy. 7Bn Royal Irish Rifles and 7Bn Royal Irish Fusiliers reached Hans Crescent on the Guillemont road.

At 17.25 8Bn Royal Dublin Fusiliers passed through Ginchy as the other Irish units cleared the west of the village. Several German counter attacks were repulsed. During the night 1Bn Welsh Guards and 4Bn Grenadier Guards relieved the assaulting units.

Ed

See under "Articles" the item on the memorial at the Crich tramway museum