Up the Line

Chairman’s notes

Good evening and welcome to the June meeting. We reach halfway through this momentous year. I am hoping that many of you will attend the event in Heaton Park on 1 July.

I shall be in France on the main day, but have not yet decided whereabouts I shall be at 07:30. Meanwhile, I am still pursuing speakers for 2017 and I am pleased to confirm that Professor John Derry will be speaking to us on Third Ypres next year.

In the last days of May and early June two significant events at sea affected the nation. The Battle of Jutland will be have been covered in great detail and I will reserve judgment on the various media events that will have occurred before this meeting.

Although strictly a member of the government, the highest ranking officer of the war died at sea early in June 1916. Horatio Kitchener was therefore unable to see how his New Army would perform on the Somme. By 1916, Kitchener was losing his creditability within the political and military circles. He was unable to allow proper delegation of work and had developed a reputation for interfering in relatively minor matters. Nevertheless, he was still held in high regard by the general public for his earlier adventures in the Empire. His loss at sea was, of course, a great propaganda boost for the enemy.

Tonight, I am pleased to welcome back Professor John Bourne to our Branch. John has had a long and distinguished career and is currently at the University of Wolverhampton First World War Studies Department. Many WFA members have taken the opportunity to take the MA Course on the history of the Great War. John gave his talk on the hiring and firing of officers in the Great War here, which was recorded by the national WFA. His last talk on various local war memorials was most interesting.

Tonight, John is talking about four separate days during the conflict that had a fundamental effect on the outcome of the war. By the end of his presentation you will know if you had guessed correctly which ones they were!

Terry Jackson, Chairman.

Last month’s talk

Jon Bell, a former RAMC officer, gave the Branch an illuminating and fascinating presentation on the role of the RAMC. By comparing the Corp’s experiences in the Great War and its present capabilities within the technological era, the unit’s importance in the earlier conflict was shown to be just as innovative for their day. The Corps can of course, be proud that the only man to be awarded the VC twice in the Great War, Noel Chavasse, was an RAMC man.

Battle medicine relates to the human body, so the main principles apply at all times. Casualty evacuation; wound management; blood; surgery; diagnostic training and facilities are equally relevant both then and now. Only antibiotics, which were not discovered until 1928, were unavailable to the earlier medics.

In the Great War, the procedure of casualty treatment began at the point of wound. Stretcher bearers would bring soldiers to the Regimental Aid Post. Although these men had little training, their efforts on the battlefield often cost them their lives. If successful, the wounded would report to the single Battalion Medical Officer. Depending on their wounds, men would move to the Casualty Clearing Station, a Base port, then a ship to Blighty. Casualties were then sent to hospitals in all parts of the country. Many buildings were requisitioned for this purpose. (For an interesting website on local hospitals, search GM 1914 Stockport Schools and Military Hospitals. The building nearby on Greek Street is shown. Ed.).

In the modern era all soldiers have medical training. After Korea, casualties could be evacuated by helicopter and if necessary home by jet. Both aircraft are capable of continuing treatment in flight and the specialised aeroplanes are fitted out as a working surgery.

The first modern industrial war caused casualties who survived, but were left with horrific injuries. Facial disfigurement was common and obviously a terrible burden for a soldier to contemplate. Fortunately the medical profession had inspired men who set the grounding for the modern plastic surgery, which we now all accept for granted. But this had to be done without antibiotics

Harold Gillies, a New Zealander set the standards with ground-breaking work. A pedicle tube, grafted from the soldier’s skin allowed the blood flow to the injury. Some of the photographs showing the initial wound and the ultimate ‘finished product’ are absolutely amazing. A saline treatment would help with the treatment and this developed into the modern era of plastic surgery as we know it. Sir Archibald McIndoe was a cousin of Gillies and treated the members of the RAF ‘guinea pigs’ in the last war. Many airmen suffered horrific burns and often had to ditch in the sea. An analysis of their treatment showed that they recovered better from burns than those who came down inland. The obvious inference that a saline solution aided recovery was thereby confirmed.

The development of prosthetics has been well documented. Thousands of men lost limbs in the Great War. Whilst the early models have no comparison to modern day technology, they did give some respite to soldiers. Modern technology can now give back to a soldier a substantially enhanced quality of life. Orthopaedic surgery or musculoskeletal surgery was pioneered by Robert Jones.

Blood is the life flow of all creatures and the development of blood transfusion has progressed. In the Great War transfusions were made, but the modern advances in science now mean that blood can be provided in a form most suited to the individual and the wound to be treated.

The development of X-rays stemmed from a discovery by the German scientist Rontgen in 1895. Some were applied during the Boer War, but the exposure times were long. Madam Curie was associated with X-ray development in the Great War and she even drove an ambulance. Her long term exposure to radiation was the cause of her death and safety procedures are naturally extremely strict nowadays.

During the Great War, soldiers would have to endure severe pain for long periods, whereas nowadays nerve blocks reduce this effect on the casualty. During the Great War British forces fought in several theatres of action. The only way to get badly injured men home often involved a lengthy sea voyage on a hospital ship. We have already seen how, nowadays, casualties can be brought home much quicker by air, whilst getting ongoing treatment in the specially adopted jet aircraft.

This was an excellent and well documented presentation. The most moving photograph was that of a young modern soldier who had lost three limbs, being able to cradle his newly born daughter with his replacement limbs. Soldiers from the earlier conflict would have been unlikely to survive the shock of multiple amputations. How many fathers and their children were denied this opportunity between 1914-18? Ed.

100 Years ago

On 14 May 1916, Lord Stamfordham, Secretary to the King, received via the War Office, a telegram. This had been sent by the Tsar concerning a proposed visit to Russia by Lord Kitchener and was unknown to the King. Kitchener had to explain this was proposed to facilitate Russian purchase of munitions, whilst trying to encourage their efforts in the war.

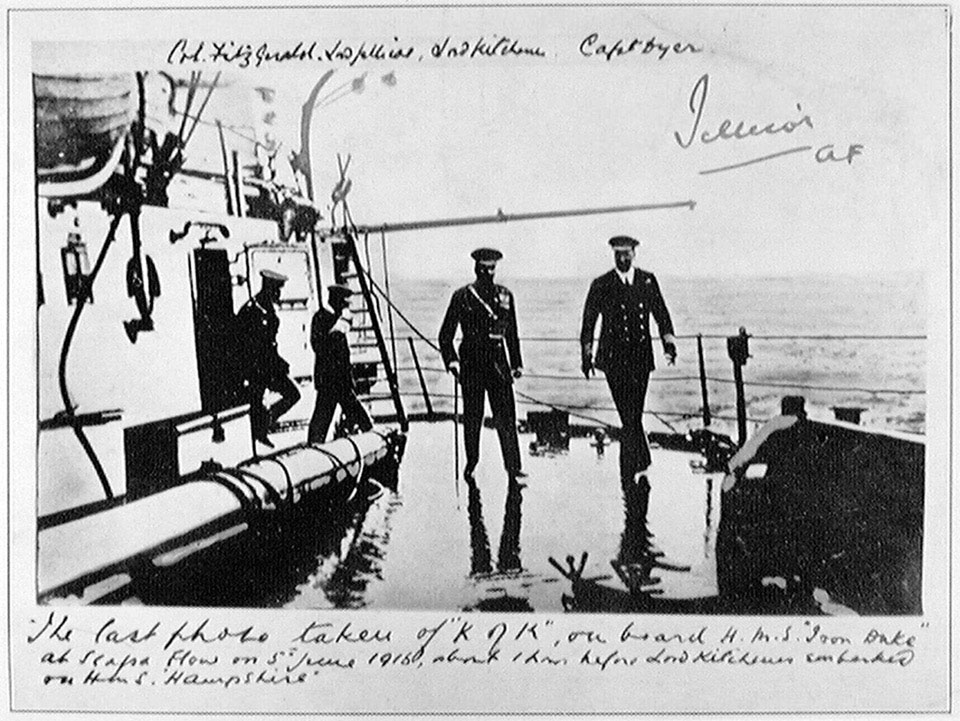

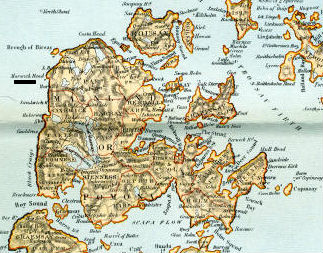

Kitchener had asked Chief of Naval Staff Sir Henry Oliver to arrange his visit. Oliver was unaware that U75 had already left for the Orkneys to lay mines. (See map of the Orkneys below right.) These were aimed to sink the British warships at Scapa Flow, the Germans being unaware of Kitchener’s proposed trip. HMS Hampshire, a cruiser (photo left), was chosen for the trip. Meanwhile U75 laid twenty two mines, mistakenly near Marwick Head rather than the area used by capital ships. (See photo of a mine at the foot of the page.)

Kitchener headed north from King’s Cross in a special carriage. His entourage included Sir Frederick Donaldson, chief adviser on munitions; Wilfred Ellershaw, Staff Officer WO, and Hugh O’Beirne, a diplomat based in Petrograd. Kitchener’s personal assistant Oswald Fitzgerald also travelled. In later years Fitzgerald’s and Kitchener’s relationship has been much scrutinised.(See photo at foot of the page left of Kitchener on the Iron Duke, taken before he embarked on the Hampshire.)

Whilst in the Orkneys, Kitchener met Jellicoe before proceeding to HMS Hampshire. (10,850 tons, four funnelled cruiser, with 730 crew*). Captain Savill made his cabin available to Kitchener. Due to the weather, the eastern part of the mainland could not be swept for mines. It was thought that German mine laying submarines could not reach the western shores, so the Hampshire was to be routed past Marwick Head. At 04.45 on 5 June she sailed out of Scapa Flow and met her escorting destroyers HMS Unity and HMS Victor. A strong gale hampered progress and as the vessels turned north into wind, both destroyers struggled to keep up with the larger warship. As submarines were unlikely to risk such heavy seas, the escorts were given leave to return to base.

Hampshire continued alone about one and a half miles off the western coast of the mainland. Whilst the heavy seas negated the threat of submarines, they caused the ship to pitch steeply. In calm seas, she may have passed over the mine safely. At 07.50 a young boy and his father on Marwick Head saw the cruiser. Suddenly a small cloud of black smoke near the bow was observed. The man saw the ship turn to starboard and believed it was going to be beached.

On board, after the explosion, the lights failed and power was lost. Captain Savill realised the vessel was doomed and gave the order to abandon ship. After about ten minutes the stern suddenly lifted, almost somersaulted and sank into forty fathoms. None of the survivors were aware of what happened to Kitchener.

As it was now daylight, the alarm was quickly raised. Locals made their way by motor car and carts towards the scene. They were prevented by the military from getting close to the coastline and the civil lifeboat was not called out. Many naval vessels were ordered to the scene, but by then most on board had gone down with the ship or perished in the cold water. The bodies that were recovered (approximately 100) are interred in a communal grave in Lyness Cemetery, Hoy. (Lt. MacPherson, a translator of Russian, has a separate grave). Oswald Fitzgerald is buried in Eastbourne. There were twelve survivors.

Kitchener’s death shook the general public and the troops serving at the Front. However, especially amongst the politicians, there were considerable efforts to set some unpleasant information to bed. Churchill and Sir Ian Hamilton saw it as an opportunity to divert the attention away from their mishandling of Gallipoli and Asquith believed Kitchener’s death would hide the soldier’s faults. However, when he lost power, Asquith spoke highly of Kitchener to Haig’s staff.

Ed *Recent research suggests there may have been up to 730 crew, rather than the 650 initially thought. See also Hampshire memorial and Hampshire centenary for details of the wreck and current commemorations. The newspapers are also currently suggesting there may have been gold bullion on board the ship.