The story of the Empress Queen

Terry Jackson

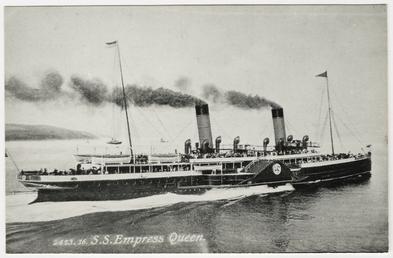

The Empress Queen was well known to the travelling public for her regular service between Liverpool and Douglas. She was a great favourite due to her fast runs and the ease with which she carried her two thousand passengers. She stood for the high water mark of the Paddle Steamer. Built by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in 1897, she was the fastest Channel steamer of her day. Length 360 ft Breadth 42 ft 3 in Depth 17 ft Gross tonnage, 1,995, with an indicated Horse Power of 10,000.

For the conveyance of troops across the Channel she was an ideal ship and it was for this purpose she was chartered by the Government on 6 February. Her fitting-out at Barrow took a fortnight. Two days after her arrival at Southampton she sailed from there with nineteen hundred men of a Scottish regiment for Le Havre. She remained on this service, getting a good opinion from the transport authorities for her regular and fast passages. She never had to stop for bad weather, nor for engine trouble. She was crowded with outgoing troops to and from Southampton.

Everything went well until 1 February 1916 when, returning from Le Havre with thirteen hundred men during thick weather, she ran ashore about 5 am on the Ring Rocks at Bembridge, Isle of Wight, a quarter of a mile from the cliffs. She ran well up on these flat rocks at about half-flood tide and lay nearly upright with the fore end embedded in the rocks, and the after end afloat.

The troops were taken off by destroyers and other craft, which came alongside in reply to her calls for help. The weather was calm and there was no danger to life. It seemed at first as though it would not be a very difficult matter to refloat her. Efforts by means of tugs and the ship’s engines were made to move her, but it was realised to be an impossible task. About a hundred and twenty men were engaged on this task and the weather was becoming rapidly worse.

That night it blew a gale and everyone on board had an anxious time. In the morning things were so bad that the Bembridge lifeboat was called out at 9.30 am to take off all hands. However, as the lifeboat house was about two miles from the wreck and the wind dead ahead, it took a long time to get anywhere near the Empress Queen. It was decided that the best plan was to wait until low water and then land the men on the flat rocks which formed a sort of natural pier, alongside of which the lifeboat could lie. At 2 pm the rescue work commenced and boatload after boatload was safely landed until the water was so low that the lifeboat grounded and was damaged. The remainder of the crew were taken off by the two fishermen in their small boat. By 5 pm all hands were landed, including the ship’s cat and dog.

The Empress Queen

The Empress Queen

By next day, the vessel had been swept from stern to stem by huge seas, piling up ropes and furniture on the foredeck in a confused mass. All the rooms had been gutted. The spar deck aft had been beaten down by the seas, and the ship, being full of water, did not float again. Up to this time the after-end of the ship had been afloat at high tide and the saloons were quite dry. Unfortunately, during the gale the after deck-house was smashed, and the saloons were flooded. All compartments, including the engine room were now filled with water at high tide. There seemed to be little hope of refloating the ship.

The Empress Queen docking at Liverpool

The Empress Queen docking at Liverpool

Efforts to get the water out were made with the assistance of motor-driven pumps from the dockyard. It was soon found to be a lost cause and the only thing that could be done was to save as much of the ship’s gear as possible. These efforts at salvage were ably assisted by Mr J Halsall, superintendent carpenter, and much valuable property was saved. The chief engineer, George Kenna also stood by and rendered valuable help.

The Empress Queen remained a very conspicuous figure for a long time after she was stranded and could be seen by all vessels navigating Southampton Waters. The two big funnels seemed to be always in view during the daytime, and were still standing there on Armistice Day. In the summer of the 1919 during a heavy gale which lasted two days, the funnels disappeared

Salvage operations were finally put into the hands of a contractor, who, with a gang of workmen, recovered a large amount of valuable metal from the engine room and other parts of the ship. It was only during the summer months that the work could be safely carried on. The temptation to work later on in the year when the weather was bad, cost the contractor his life.

The wreck of this splendid paddle steamer was the cause of great regret to thousands of people in Lancashire, with whom she was a great favourite. For eighteen consecutive seasons she had carried them safely across to Mona’s Isle, and it was hoped that, when the war was over, she would resume her old occupation, but this was not to be.